Talking to Your Children about Death

This from “Death and Dying, Life and Living” (Page 346):

In our society, adults often wonder if they should talk to children about death, what they should say, and how they should act with children in death-related situations. These questions arise in many ways:

Should we discuss death with children or teach them about loss and grief even before a death takes place?

What should we say to children after a death occurs?

Should we take children to funeral services?

Perhaps the most difficult of all questions of this type arise in situations in which adults (parents, family members, or care providers) are challenged by a child who has a life-threatening illnes and who is facing his or her imminent death.

One recent contribution to the discussions (Kreicbergs et al., 2004) described a study of Swedish parents whose child had died from cancer between 1992 and 1997. Among the 561 eligible parents, 429 reported on whether they had talked about death with their child. Results showed that more than a quarter of those who did not talk with their child about death regretted that they had not done so. Similar regrets were reported by early half of the parents who had sensed that their child was aware of his or her imminent death. By contrast, among the parents who had talked with their children about death, “No parent in this cohort later regretted having talked with his or her child about death (p. 1175).

The implications of this study suggest that, despite all of the challenges involved in talking to a child about death and even in the very demanding circumstances of a child facing his or her imminent death, it is most often better to go ahead with such conversations. The main reason for this is that, as Rabbi Earl Grollman has often said, “Anything that is mentionable is manageable.” Opening a line of communication with children is preferable to allowing them to try to cope on their own with incomplete or improperly understood information and the demons of their own imaginations. In addition, a child who is able to have his or her concerns addressed in a thoughtful and loving way is a child who has someone he or she can trust when there is a need to look for a source of support.

I Don’t Smile When I Embalm Bodies

Earlier this week a contentious discussion brewed on my Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook page. And I’d like to address the topic in my blog’s forum.

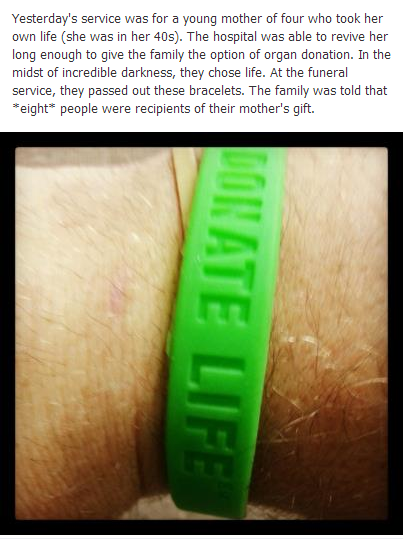

The discussion was kick-started when I posted this status:

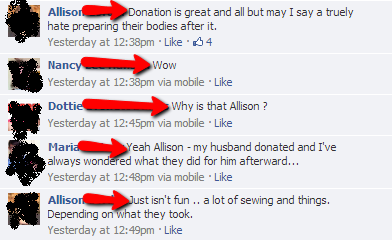

The second comment on the above status was from a fellow embalmer named Allison, who said this:

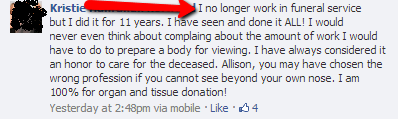

Allison’s initial comment eventual prompted this comment from a former embalmer named Kristie.

First off, let me say it’s possible for an embalmer to be both 100% for tissue/organ donation and not enjoy the process of preparing a donor. It’s possible for us to be both professionals and human. I’m one such funeral director. I am firmly and unequivocally a supporter of those who choose to find life in a tragic death, and yet when a donor body comes through the morgue door, it’s not Christmas morning.

I know that the best donors are usually young and they usually die from tragic (not necessarily violent) circumstances that leave their body in decent condition to be harvested.

I have immense respect for families who — in the midst of incredible tragedy and darkness — find a way to overcome their pain and chose life by allowing for the harvesting of a body they love so dearly. This act of donation is one of the few genuinely unselfish acts to be found in humanity.

Yet, while I recognize the intense moral beauty and life saving value of organ donation, I’m less than excited to embalm and prepare a donor’s bodies.

Each funeral home and funeral director is different. Some funeral homes are large enough to have shift work; still others are large enough to employ full-time embalmers, who basically embalm body after body all day. Some funeral homes have secretaries, prearrangement directors, at-need directors, full-time pick-up people, etc., etc. But for many of us small firms, we play role of embalmer, secretary, pick-up/livery person, funeral director, at-need director and pre-need director. We’re on call 24/7 and rarely have an uninterrupted holiday.

Our personal lives are not just blurred with our professional lives, they become one and the same, often resulting in sad endings. Divorce. Depression. Burnout.

Our pay doesn’t always justify what this profession takes from us. According to the BLS, the average embalmer makes $45,060, which isn’t bad until you consider that the salary often comes at the expense of our souls. I’ve worked 20 hour days. I’ve worked 100 hour weeks. Most months I get two days off. This month, my weekend off happens to be this weekend and with the snow coming, I may have to work the plow on one of my “days off.” And when I am home, it’s hard to get comfortable as I’m one phone call away from going back to work.

I was up until 12 midnight writing this post and then at 3:30 AM I was called into work. I won’t be finished work until roughly 5:30 PM.

Here’s a picture of me at the nursing home at 4:40 this morning. The smile is real … the nurses were making fun of me for taking the photo.

And although this isn’t about me and the burdens I carry, I will say that my experience isn’t exceptional. The at-need demand, emotional and long hours take their toll on us as people.

So, when the heart is donated and I have to raise six arteries instead of one, I don’t smile.

When there’s bone donation, I don’t look forward to moving the Styrofoam rods around to make the appendages look natural.

When skin is grafted, I don’t smile when I’m cleaning the seepage off the floor.

When I get various liquids on myself because of the intrinsic messy nature of donor bodies, my face doesn’t crack a grin.

Unless I’m listening to stand-up comedy on the morgue’s radio, I don’t embalm bodies with a smile.

I appreciate Kristie’s assertion that she has never thought about complaining when preparing a body. And I appreciate that she always sees it as an honor. I will be the first to admit that Kristie is probably a better person and funeral director than I am. Maybe her suggestion to Allison (that Allison should find another profession) applies to me as well.

But, I, in contrast to Kristie, think it does us funeral directors well to be honest. Maybe not in a public forum like I’m doing now, but we need to recognize that we’re both professionals and human. We love to serve you, but there’s times when we too need to be helped. We need to fight that perception that to be a professional means being an unfeeling robot. We need to ask for help, sometimes we need to seek counselling. If you’re a funeral director and you don’t embalm donor bodies with a smile, it’s okay.

15 Questions about You and Death

Back before Twitter, before Facebook, before Gmail, around the same time that Hotmail was cool, there was this place called the “Myspace.” And on this “Myspace”, it was a common practice for the members of the “Myspace” to answer a litany of random questions and then post one’s answers to said random questions so that all one’s friends could see the answers.

Let’s go back to the age of indestructible Nokia cell phones, to the time when you connected to the internet through dial up, and let’s pretend it’s once again cool to have frosted tips and answer random questions.

One. Are you a death virgin (have you had anyone close to you die?).

Two. When you die, do you want embalming, cremation or other?

Three. Who is your current crush? (Had to throw that one in there for old times’ sake)

Four. If you could choose, would you rather die having sex, or die while saving an old person from drowning?

Five. Would you rather die slowly (so that you could say your “good-byes”) or fast (so that you could have minimal pain)?

Six. Does the most epic way to die necessarily involve Chuck Norris?

Seven. Do you believe in the afterlife?

Eight. On a scale of one to ten (with 10 being the highest), how would you rate your fear of death?

Nine. Should voluntary active euthanasia be legal or illegal?

Ten. Have you ever touched a dead person? If so, how would you describe that experience?

Eleven. If you died today, would you be happy with your life? If no, what would you regret?

Twelve. What do you think is worse: outliving your spouse or outliving your children?

Thirteen. If you could come back as a ghost, who would you haunt?

Fourteen. Worst death ever in a movie?

Fifteen: If you believe in God, do you think he knows the day, hour and minute when you’ll die?

Reach back, grab some nostalgia and answer these question in my comment feed.