Words From a Grieving Friend

A facebook and real life friend posted this in his status yesterday. It was so good that I wanted to share it with you.

If you know someone who is grieving, this is probably how they want you to treat them:

Dear Friend,

Please be patient with me; I need to grieve in my own way and in my own time.

Please don’t take away my grief or try to fix my pain. The best thing you can do is listen to me and let me cry on your shoulder. Don’t be afraid to cry with me. Your tears will tell me how much you care.

Please forgive me if I seem insensitive to your problems. I feel depleted and drained, like an empty vessel, with nothing left to give.

Please let me express my feelings and talk about my memories. Feel free to share your own stories of my loved one with me. I need to hear them.

Please understand why I must turn a deaf ear to criticism or tired clichés. I can’t handle another person telling me that time heals all wounds.

Please don’t try to find the “right” words to say to me. There’s nothing you can say to take away the hurt. What I need are hugs, not words.

Please don’t push me to do things I’m not ready to do, or feel hurt if I seem withdrawn. This is a necessary part of my recovery.

Please don’t stop calling me. You might think you’re respecting my privacy, but to me it feels like abandonment. Please don’t expect me to be the same as I was before. I’ve been through a traumatic experience and I’m a different person.

Please accept me for who I am today. Pray with me and for me. Should I falter in my own faith, let me lean on yours. In return for your loving support I promise that, after I’ve worked through my grief, I will be a more loving, caring, sensitive, and compassionate friend-becauseI have learned from the best.

Love,

(Your name)

By Margaret Brownley

Join Me in Empathy as I Travel to Guatemala with World Vision

A couple years ago we had a late night house call. We drove up to the house, and an uncle came outside to meet us, explaining the situation we were about to enter.

“You guys are here for my niece, Sara.

She’s 16 years old.

Been fighting cancer for four years.

She’s in the living room with her mother, Joan.”

We entered the house, walked to the living room and were greeted by about 20 family and friends that were scattered all over the living room, some sitting, and some standing, others laying on the floor.

When a terminal person is dying under home care it’s normal for a hospital bed to be temporarily set up in a large room, enabling larger groups to visit the dying. In this case, the bed was in the living room, but the deceased wasn’t to be found lying on it; which was very unusual. We allowed them time to explain who Sara was, what she meant to them. All families need this time. They need to believe that through their stories Sara would be incarnated in us, so that we could love her the same … so that we could become a part of their family. Once we’re apart of “the family”, we no longer represent a cold funeral director, but a tender caregiver.

After their stories, we asked them if they were ready for us to make our removal. They all had said their last “good-bye”. And then we asked, “Where is Sara?”

“She’s here”, said Joan the mother. And then we saw her. When we first walked into the living room we saw a small girl being held by Joan. The girl looked to be around ten years old, and being that it was late we just assumed that this was one of Sara’s younger sisters who had fallen asleep in Joan’s arms. But, it turned out, Sara had died in her mother’s arms and there she laid.

Like the transfer of a sleeping child from one adult to the next, I got down on my knees, slide my arms under Sara’s head and thighs, lifted her starved body out of her weeping mother’s lap and carried her to our stretcher. The room was full. Full of love. Full of grief. Full of tears. And I was a part of it all.

Empathy.

I tell you this story because I want to make a distinction between empathy and sympathy. Let me explain the difference:

Imagine being at the bottom of a deep, dark hole. Peer up to the top of the hole and you might see some of your friends and family waiting for you, offering words of support and encouragement. This is sympathy; they want to help you out of the pit you have found yourself in. This can assist, but not as much as the person who is standing beside you; the person who is in that hole with you and can see the world from your perspective; this is empathy. — Dr Nicola Davies

There are times (at funerals especially) when all we can give is sympathy. When it’s outside of our ability to fully empathize with a person’s situation. But, there’s other times when you can’t help but be drawn into the narrative, so that you enter the narrative and become a character in the story. Not just a narrator, but an actual character in the drama of life and death.

Too often when child sponsorship programs like World Vision attempt to gain your support, they appeal to your sympathy. “Look at this poor, starved, naked child as he picks food out the dumpster. His distended stomach looks like a balloon and those flies around his face are the only friends he has.” Sympathy appeal, expected to make you go, “O.M.G. If I only spend $40 a month I can give him some rice and … maybe I’ll send him an iPad for Christmas.”

And sympathy works … it creates donors.

But I want to invite you to empathy.

Mother Teresa said, “Do you look … at the poor with compassion? They are hungry not only for the bread and rice, they are hungry to be recognized as human beings.” This “recognition” involves more than food, it involves

education,

health care,

economic development,

spiritual care

and food, agriculture and clean water.

All recognition factors that World Vision does in Guatemala and abroad.

In September I’m going with World Vision to Guatemala to visit a child that I sponsor. And I want you to sponsor a child as well (here’s a link to World Vision’s Charity Rating). In fact, my goal is to have 50 children sponsored by you, my readers.

So, I’m inviting you to empathy. I’m not selling you something or playing on your sympathy. No, I want you to get down on your knees, look into the eyes of someone you don’t know, learn about them and walk with them as they grow.

Enter a story.

Click here to sponsor a child in the village that I will be visiting. And, if you sponsor or not, help me reach my goal of 50 sponsorships by SHARING this post.

It Was a Normal Death Call Until The Family Tackled Me

The following post was submitted by a funeral director who wishes to remain anonymous. While the names have been changed to protect the privacy of the parties involved, the circumstances and events that you are about to read are entirely true.

*****

Jane Doe had been a prominent and well-known local politician. She had been on hospice for a short time. Upon arriving at Jane’s, typical suburban house, at the end of the culda sac, I counted about 15 cars parked around her house. I couldn’t help but think, “Wow! Jane was very well loved, and there are a lot of cars here for 2am.

Upon ringing the door bell, I was greeted by John, her husband of 30 years. He couldn’t help but apologize for “waking us up at such an ungodly hour”. After speaking with John, and asking if he was ready for us, he replied, “Yes” and invited us inside. Internally I thought this will be straight shot, piece of cake pickup.

What I failed to gather was the mood of the people in the house … the quiet before the storm. Jane had been in the living room. Me and my partner gather our required equipment, and made the 50 foot journey to the living room. I began my speech, “if you would to stay and watch and help, you’re more than welcome too. Please do not feel as if you have to leave the room.” No one wanted to help us move Jane, but they all decided to stay and watch.

Upon getting Jane onto the stretcher, I was entirely unaware of the mass hysteria about to unfold in front of my eyes. After I moved Jane onto the stretcher, I began to tighten the strap when Jane’s body, due to the force of me strapping her in, belched.

Mass hysteria erupted. I was literally tackled away from the stretcher, 911 was called, and the teary eyed people now became violent, as to them I was taking their very much ALIVE loved one who had not died. I was sat upon, as the police and ambulance were on their way. What was probably only 3 minutes seemed like an eternity and I could only think of one thing, “where is this hospice nurse?!”

Upon the authorities’ arrival, I was able to explain my predicament. And that the belching that had occurred was a natural and actually fairly common phenomena for the dead. The police officer, fireman, and ambulance driver cracked a knowing smile and helped me restore the peace as I took Jane into my care.

They even escorted us to the funeral home. John, upon seeing me the next afternoon to make arrangements, immediately burst into laughter, saying, “Sorry about last night, my family loved her very dearly.” My only response was to politely say “I would have done the same thing had I not known better.”

10 Burdens Funeral Directors Carry

Note: I wrote this article over the weekend and I wasn’t going to publish it until Wednesday, but since I just spent my entire night [11 PM to 5:45 AM] picking up three deceased persons, I thought it’s probably appropriate to post it now. After I hit “publish”, I’ll be off to bed and back to work by noon. Ah, the joys of a small family business.

If you’re in the Parkesburg area and want to donate coffee* to my bloodstream, you’ll find me at 434 Main St.

*I prefer a medium cup of Dunkins Donuts with cream and sugar : )

*****

The following burdens are not necessarily funeral service specific, but many, if not all, come with this profession. Those of us who stay in this profession do so because we find serving others in their darkest hour extremely rewarding, yet there are burdens to be borne. Here’s ten.

One. A Lack of Personal Boundaries.

The phone rings at 3 AM in the morning with a hospice nurse on the other end of the line telling you that so-and-so has died, that so-and-so’s family is requesting your services and that the family of so-and-so is ready for you to come and pick up so-and-so.

The phone rings at 6 PM the next day. Someone needs to see so-and-so … he simply can’t believe so-and-so is dead and must come to the funeral home at once to see so-and-so.

Two. Depression.

While those of us who stay in this business do so because we love serving people, the lack of personal boundaries can lead to depression.

Depression, because my son’s baseball game was at 6 PM, but somebody in so-and-so’s family needed to see so-and-so this very minute. Depression because the emotional needs of others somehow always trump my personal life needs. And all of a sudden “I’m not a good father” and “I’m not happy with my life.”

Three. Psychosis.

Psychologist Carl Rogers described how he “literally lost my “self”, lost the boundaries of myself…and I became convinced (and I think with some reason) that I was going insane”. When we in human service, and death service, become pulled into the whole narrative of death and dying, we can lose ourselves.

Four. Smells.

An iron stomach I have not. Putrid smells, this business has many. This is a burden that comes home with me … a burden that my wife often notices shortly after I walk through the door.

Five. Life Secrets, Death Secrets and Practice Secrets.

When a person commits suicide or dies from an overdose, there are times when the family simply wants to keep the manner of death a secret from the public.

I don’t mind carrying the burden of a secret, but when you live in a small town where suspicion can run rampant, secrets can become heavy.

Some things we see will remain with us forever. They are so disturbing, so terrible that we do the world a favor by not sharing them.

Six. Isolation by Profession.

Death makes us different … not necessarily unique, just different. This difference creates a chasm between us and those not immersed in death. Sure, police, doctors, psychologist, etc. have chasms created by their professions, but ours – because of the fear, sadness and undefined hours of our practice – creates us into something other.

Seven. Death itself.

Death can be a beautiful experience in the life of a family. But when that death is tragic and unexpected, death is a heavy burden for both the family and for those who serve the family. Specifically, when the death is a young person, our entire staff becomes agitated and moody.

Eight. Workaholism.

Many funeral homes are small businesses that don’t have enough staff for shift work. In order to serve our families (so that they’ll return), we have learned that the way to overcome the depression and potential psychosis that can come with a lack of personal boundaries is to marry the business. We make the work our life. Such work addiction pleases the families we work for, but can leave our personal families destitute.

And while many of us don’t carry the burden of workaholism, we do carry the burden of fighting off the addiction.

Nine. Death Logistics Stress.

Every business has stress. Some more and some less. And while funeral service can’t claim a quantitative difference in stress, it can claim to have its very own type of stress. To grasp the type of stress surrounding a funeral, imagine planning a wedding in five days, except where there’s joy, sadness exists, and where there’s usually a bride, a dead body lies in state.

Ten. Dress clothes …

… in the summer heat. Dress clothes in the dead of winter. We are one of the few — armed service members are the only others I can think of — professions that wears suits outdoors as a matter of practice. There’s nothing like having sweat drip down your back and into your crack. Well, nothing except maybe freezing your dress shoe covered toes in a foot of snow.

Breaking the Isolation of Stillbirth

Today’s guest post is written by Samantha Allington.

****

On Thursday 8th September 2011 I was 19 weeks and 3 days pregnant when my waters broke at home. I knew in that instant that my baby wouldn’t survive but I still wanted to hang on to the little bit of hope that some miracle would happen and my pregnancy would proceed safely against the odds.

I was rushed in to hospital by my birth Doula where I was checked over by the doctor who confirmed I had lost amniotic fluid. After a scan to measure the fluid levels I was told there was not enough water to support my baby’s lung development and that due to diabetes I was at high risk of death too.

I had to face the hardest decision of my life and after spending from then till the Monday following refusing outright to terminate my pregnancy, I finally conceded to allow the medical team to induce labour at just 20 weeks gestation. There would be no intervention to save my baby as I was under 24 weeks pregnant and hospital policy didn’t permit resuscitation at that age.

I was in an abusive relationship with a violent partner and I chose to go through labour and birth with only my Doula present. It was a harrowing experience to say the least but I was still determined to make my baby’s birth as natural and beautiful as I could. I wanted it to be special and memorable, for my last moments with my baby to be precious.

We had a candle lit room (LED tea lights and colour changing lotus flowers), aromatherapy, crystals and the Obstetrician permitted me to have a natural birth without any electronic monitoring (no wires or drips) so that I could move around freely. The midwives allowed us the space we desired and only came in to check once in a while how contractions were developing.

Finally it was time to give birth and despite holding on for as long as I could refusing to push, my daughter finally entered the world at 5:28am on 14th September 2011 at just 20 weeks and 2 days gestation as the sun was rising.

She was about the size of a Barbie doll at just 20cm length and weighing a tiny 10.5 ounces. Despite her tiny size she was perfect in every way, with ten fingers, ten toes, perfectly formed ears and a little pink nose, I even noticed in the right light she had the fairest eyelashes I’d ever seen.

I spent 2 days alone with her in the hospital, holding her, kissing her and trying to take in every little feature so that it would be burnt to memory forever. I didn’t want to let her go or say goodbye, I wanted those days to go on and never end, but of course they did end and I had to leave the hospital.

I spent 2 days alone with her in the hospital, holding her, kissing her and trying to take in every little feature so that it would be burnt to memory forever. I didn’t want to let her go or say goodbye, I wanted those days to go on and never end, but of course they did end and I had to leave the hospital.

Arriving home it was time to start planning her funeral, she’d never get a birthday, Christmas, Easter or a wedding day, her funeral was the only special occasion she would ever have, and the only thing I could do for her to make it as important and special as I could. I contacted the charity Children Are Butterflies who work alongside B Hollowell and Sons funeral directors. They fund children’s funerals and the lady that runs it was lovely.

Due to the abusive relationship I was in, I was again alone in planning my daughter’s funeral but Ann made everything go easier and smoother. She was so kind and supportive towards me and I know I will be eternally grateful to her for all she did.

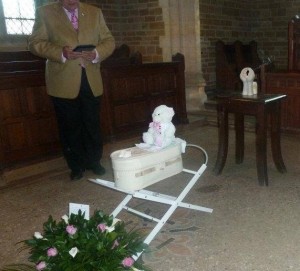

The funeral was beautiful. We had a Hearse that was made from an old London black cab to take Poppy-Rose to her last resting place and a beautiful white woollen coffin with an embroidered name plate. The funeral was white, pink and butterfly themed. Poppy’s coffin looked so tiny at the front of the chapel resting on a Moses basket stand that was far too big. We read poems and I gave her Eulogy before moving to the graveside for her internment. Each guest was given an incense stick to light and place in the ground around her grave and a paper butterfly to write a message on for her. As we said goodbye a beautiful red butterfly flew across her grave, unusual for the time of year here in England.

The funeral was beautiful. We had a Hearse that was made from an old London black cab to take Poppy-Rose to her last resting place and a beautiful white woollen coffin with an embroidered name plate. The funeral was white, pink and butterfly themed. Poppy’s coffin looked so tiny at the front of the chapel resting on a Moses basket stand that was far too big. We read poems and I gave her Eulogy before moving to the graveside for her internment. Each guest was given an incense stick to light and place in the ground around her grave and a paper butterfly to write a message on for her. As we said goodbye a beautiful red butterfly flew across her grave, unusual for the time of year here in England.

I wanted to share my story because often talking about baby loss is considered taboo but especially in cases of termination for medical reasons. This leaves so many women (and families) feeling isolated and alone in their grief. I wanted a chance to give my side of the story, to show you how much we all need that little bit of help, compassion and love. We don’t all have family to stand by us; some of us feel so alone in our grief. We go through all the usual feelings such as sadness, despair, anger but often we also feel guilt and self-blame and this can only be made worse when we are silenced by others negative judgements , we need to be allowed to speak out and to share our stories, our personal journeys with others.