If You’re Looking for a Book with Outrageous Funeral Stories …

There are a couple reasons funeral directors don’t tell their stories.

There are a couple reasons funeral directors don’t tell their stories.

One, it takes a lot of tact to narrate funeral experiences that are so very personal, so sensitive and so interconnected.

Two, the stories are often too complex to tell. We sit at the hub of multiple narratives – the deceased’s story, the family’s stories and our own personal stories – and bringing all these perspectives together in a neat digestible bit is no easy piece of writing.

And three – and perhaps the biggest reason – writer types don’t last long in this trade. Verbal processors do well as funeral directors. The introverted, self-reflective writer types can often be overburdened with the gravity of death-care.

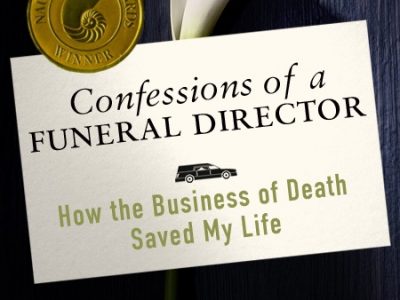

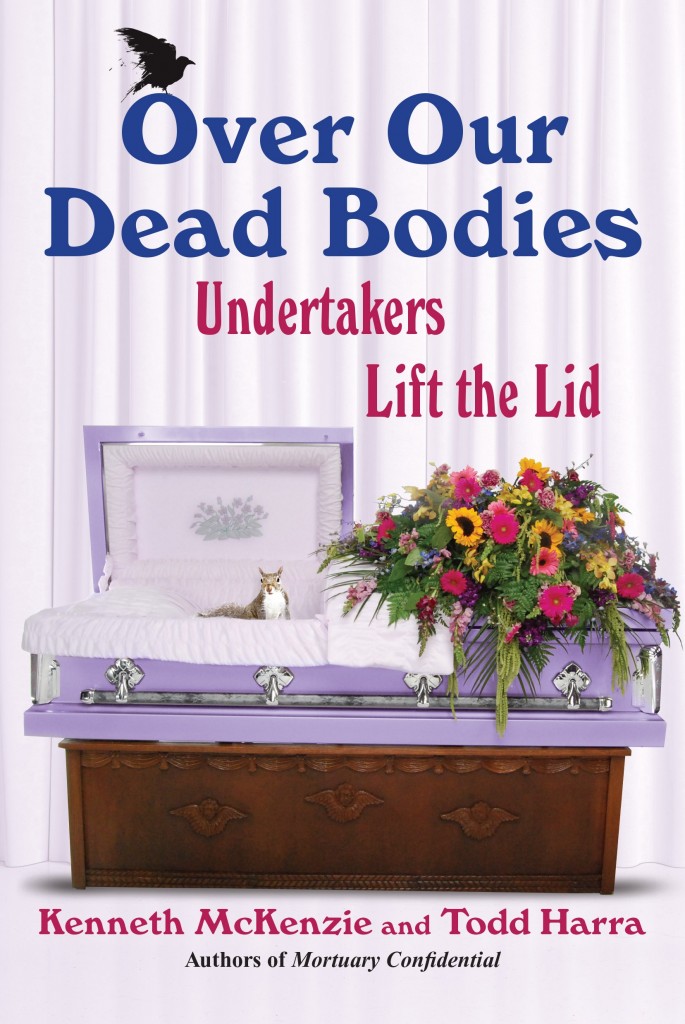

But every once in a while writer-types succeed as funeral directors and they find a way to write tactful, digestible stories that put life in death. Kenneth McKenzie and Todd Harra have not only done this once but twice in their co-written books, “Mortuary Confidential” and the newly released Over Our Dead Bodies.

I just finished reading their newest edition, which is divided up by Ken writing some chapters and Todd writing some others. Ken’s chapters read biographically. And his first story is especially outrageous. It tells of the police having to take over a funeral that went Jerry Springer. As a sixth-generation funeral director, my family has a bunch of stories we like to tell, but NONE like this one.

Ken tells of his father’s suicide and how that event inspired him into the funeral trade. He tells of his niche in the early 90s with deceased AIDS victims. He tells of the growth of his business and his foray into charity, which included the fundraising 2007 and 2008 Men of Mortuaries Calendars (Ken was the mind and money behind those projects). In fact, a portion of the proceeds from this book and the previous one go to Ken’s charity KAMM Cares, which helps women who are battling breast cancer.

Todd, a fourth-generation funeral director from Delaware, tells ten stories (from ten different people) that are dipped in beauty and morbid humor. Todd’s paints a great story and he weaves together each funeral /death related story into a stand along piece.

Overall, not only do I recommend this book as a well-written peek into the funeral industry, I also recommend it philosophically. Ken and Todd are doing what funeral directors need to do to gain back the public trust that’s been lost by a few selfish shysters. This disclosure and transparency found in Over Our Dead Bodies is what the funeral industry needs. It is the opposite of the uptight, closed-doors privacy that too many funeral directors buy into as essential to our ideal of professionalism.

So, if you’re looking for a fun book to read on vacation; or a weird Christmas gift to give to your macabre Uncle Frank; or maybe you’re interested in what funeral directors might encounter; or you simply want to support Ken’s KAMM Cares, let me recommend Over Our Dead Bodies.

When Funeral Directors Play the God Card: How I Approach Religion as a Funeral Director

There’s a number of similarities between the work of a pastor and the work of a mortician. We, like pastors, find our schedules based off the needs of others. We find ourselves continuously surrounded by mysteries and silence. We are invited into the sacred space of death; and like pastors, we’re expected to be some kind of guiding symbol through the dark valley of loss.

Like pastors, we are given great power. And we have too often abused that power by exploiting those we are meant to serve. We too – like the church – can also abuse God and religion for our own personal agendas, distorting the purity of our profession for the sake of personal gain.

In fact, too many funeral directors exploit God and religion in order to find a competitive advantage.

I remember sitting at my desk during mortuary school, probably sketching some worthless piece of pen art on the pages of my textbook. I was – like usual – having trouble paying attention to the professor as he waxed on about various means of gaining a competitive advantage in the funeral industry. And then he said something that knocked me out of my stupor.

“One of the best ways to gain customers is to go to a large church. Get as involved as you can. Meet as many people as you can. Make your donations visible. And, if you can do it, find another large church and attend there as well. Use religion to your advantage.”

At that time in my life, there was still a purity surrounding religion and God. My faith hadn’t been examined and broken down atom by atom like it is today. My trust in the goodness of humanity and the goodness of God and the love of God was as black and white as day and night. And the idea that we should use something so powerful – something with some much potential goodness (think Mother Teresa) – for a competitive advantage made my stomach turn in anger and sadness.

Today, I watch as too many of my industry colleagues (one specifically who is a competitor, who attends the two largest churches in the area, and who sat under the very same professor) take my funeral professor’s words to practice. I watch as God and church and religion become a stepping stool to a higher echelon of community endearment. And just like twelve years ago, my stomach still turns.

My faith has changed from twelve years ago. Years ago I was taught to believe a lot to believe it all with certainty; today, the opposite seems to be true. There’s parts of my faith where mystery and doubt have bred silence and where that silence has bred a form of agnosticism. But lying at the core of what’s left is still the belief that love is the meaning of things. That God is love. That our highest form of humanity is found when we love. That the universe is held together by love. And that love is how we conquer the fear of death.

A couple months ago my disobedience to my professor’s words went on full display (against my expressed wishes) in a local newspaper article. Words that were spoken in private became fodder for the public. This is what was printed:

But more than 10 years of work in the funeral industry has changed Wilde’s once traditional Christian faith, he says.

“When you see tragedy firsthand, it affects your view of God. You either change your view of God, or you lose faith. I think I’ve done a little of both.”

Though he still enjoys studying theology and religion, “I’ve become (slowly) apathetic towards God … . I know this sounds awful, but I don’t think he’s involved enough in the world.”

Still fascinated by the idea of a suffering God in the person of Jesus, Wilde says he no longer finds much meaning in the concept of a resurrection.

“I don’t see the intervening power of God in the death of a child … or in an overdose.”

For the past year, he says, he hasn’t attended church with his wife and 2-year-old son.

This article was immediately met by an onslaught of personal inquisitions. I received phone calls, emails, texts from people that I love who were concerned for my soul. Family members cried because I was now an apostate. And even though I’ve started to go back to church, I know many now see a question mark as my religious status instead of an exclamation point.

I still don’t know the long term effects of such a personal admission being printed for the public eye. I don’t know who will stop using our funeral home because “Caleb Wilde isn’t one of us.” Because “Caleb is a heretic.” I do know that my professor was right: Religion is a powerful thing. And religion and death are wonderful bedfellows. I’ve felt their power. When I doubted, I lost more than parts of my faith; as a funeral director, I probably lost parts of my business.

But, perhaps ironically, by allowing myself to doubt parts of my faith, I’ve managed to gain its purity. Because I’d rather be honest about my doubts, honest about my fears, honest about my silence. I’d rather embrace transparency and feel the ire of my community.

As a business owner in the funeral industry, it’s a great temptation to allow my identity to be molded by what I perceive to be the public’s wishes. It’s a temptation that all business owners face. But for funeral directors specifically – while recognizing the immense power and connection that religion has with death — the temptation to mold our faith for purposes of public approval may be the greatest temptation of all. It’s a temptation that I hope you don’t fall into. Because faith matters.

And the truth is that when we allow our faith to be swayed for the purposes of public approval, it is much worse than doubt and silence and disbelief.

Funerals: Touching is Safe Here

In our culture, touch is too often motivated by

1.) Desire.

2.) Demand.

Many don’t know how to touch outside of those two categories.

There’s a rather new interdisciplinary area of study called haptonomy which explores how to touch outside of the desire and demand categories. Haptonomy is the study of psycho-tactile communication. Psychologist and hospice pioneer Marie de Hennezel writes concerning her training in haptonomy:

One develops and tries to ripen one’s human faculties of contact; one learns to ‘dare’ to encounter another human being by touch. It may seem foolish to undergo formal training in order to develop a basic human faculty. Unfortunately, the world in which we all grew up and continue to develop is one that doesn’t encourage spontaneous emotional contact. Certainly we touch other people, but that’s when the intention is erotic. Other times, the context is impersonalizing, as in the medical sphere, when one is most often manipulating ‘bodily objects.’ What is forgotten is what the whole person may feel. “

There’s touching with desire, touching with demand and — here’s a third option — there’s touching with devotion. Touching with devotion is an ardent recognition of the value of people … it’s not forceful or uncomfortable, rather it’s respectful and produces ease.

There’s one place where the humanizing, respectful and relaxing touch of devotion is seen on a regular basis.

That place is death.

We receive the phone call that so-and-so has died at their home. We put on our dress cloth, drive to the house and there awaiting us is so-and-so’s family. We walk in and instead of shaking their hands, we reach for a hug. And they reach back.

Complete strangers.

At the funeral of so-and-so, family and friends hug and kiss and embrace all day. It’s those hugs and embraces that somehow make a funeral bearable … they somehow relax the otherwise tumultuous experience of death.

The irony is that a human has to die for true humanity to be found.

*****

Mainstream medicine is catching on to the power of devotional touch.

The University of Miami conducted over 100 studies on the power of devotional touch and this is what they found: Devotional touch can: produce faster growth in premature babies

caused reduced pain in children and adults

decrease autoimmune disease symptoms

lowered glucose levels in children with diabetes

improved immune systems in people with cancer.

Other studies have show that devotional touch can

lower stress levels

boost immune systems

help migraines.

Why do we reserve the life giving power of touch only for death and funerals?

What would happen if we would daily interact with our friends and family like we were at a funeral?

10 Reasons I’m a Funeral Director

Last week, a high schooler asked me, “Why are you a funeral director?” After a couple days of thinking about the question, here are ten reasons I’m a funeral director.

One: Service.

A couple years ago, a granddaughter was giving her grandmother’s eulogy at the funeral home. She shared that before she would take naps at her grandmother’s house, her grandmother would warm a blanket in the dryer, and as the granddaughter laid down, the grandma would drape the warm blanket over her.

After the service was over and before the family closed the lid on the casket, I grabbed the blanket that the family had laid in the casket and warmed the blanket. When I gave the warm blanket to the granddaughter, she couldn’t withhold her tears as now she draped it over her grandmother.

Situations like this arise regularly in the funeral profession. And, as a caregiver by nature, I find great satisfaction in seeing others have more meaningful death experiences because of my efforts. I enjoy serving.

Two: Perspective.

Emerson said, “When it is darkest men see the stars.” We try our best to deny the darkness of death; we consciously and unconsciously build our immortality projects, hoping that we can live immortally through them.

And then death. Weeping. Our projects come tumbling down. And it’s in those ashes, in the pain, in the grief, through the tears, we see beauty in the darkness. This is a perspective that funeral directors are privy to view on a constant basis. And, in many cases, the darkness can be beautiful.

Three: Affirmation.

Being told, “You’ve made this so much easier for us.” or, “Mom hasn’t looked this beautiful since she first battled cancer”, or “You guys are like family to us” means a lot to me. It’s important to know that what you’re doing is meaningful for the person you’re doing it for.

That verbal affirmation is a big reason why I continue to serve as a funeral director.

Four: Safe Death Confrontation.

When I was a child, I’d lay in bed and imagine myself dying at a young age. I imagined Death as a Monster. That fear, though, has dissipated as I’ve both worked around Death and I’ve grown to be comfortable with my own mortality and the mortality of those I love.

Perhaps there’s no greater freedom than to live life with a healthy relationship with Death. That healthy relationship allows you embracing each moment, realizing that we are not promised tomorrow. This good relationship with Death has been given to me by the funeral profession.

Five: Kisses.

From old(er) women. Big sloppy kisses from older women. And what makes it even better is if they follow up the kiss with a, “If only I was 50 years younger ….”

Six: Power and Obligation. You give us power every time you open up your family life, your deceased loved one and your grief to us. And when you give us that power, there’s a certain satisfaction that comes with treating that vulnerability with as much honor as we can.

We honor your loved one as we prepare them. We honor you as we serve you. The power you give us, and our obligation to that vulnerability is the grounds that produce honor.

Seven: Lack of the Superficial.

There’s so much BS in the world. People pursing bigger cars, bigger houses and bigger salaries, that we become so materialized we can barely stand honesty, vulnerability and spirituality.

That all changes around death. Suddenly, you wish that the time you spend pursing that raise had been spent with your dad. Suddenly, you find some honesty about your life, some perspective and maybe even some spirituality.

I hate BS. I love honesty. I love spirituality. And I love watching as death helps us become human.

Eight: Informs my Perspective on God.

Whether or not funeral directors are religious, you’ll find that almost all are spiritual. Whether or not they believe in God, death has a way of making us look at the deep, the beyond and the transcendent.

For myself, so much of my faith has been informed by the doubt of death. I see God in a whole new dark. And it’s good. In fact, I’ve come to believe that God dwells with the broken because – it would seem – he too is broken.

Nine: Constant Challenge.

Somebody said, “It’s the perfect job for someone with ADHD because there is constant change.” Constant change and constant challenge.

Whether a call at 4 AM; or a particularly tragic death; this job is always pushing us and (hopefully) makes us into stronger people.

Ten: Our Associates.

Today, a nurse – on her own free time – tracked down the hospital release for us. I told her, “You’re wonderful.” Every time we interact with hospice nurses, I always praise them for their work, for their love towards the family. When a church provides a funeral luncheon, I try to tell the workers that they are providing grace in the form of food. When a pastor totally connects with the family, I tell him/her how great a job they’re doing.

When somebody dies – during the hardest moments of life – we see the best in people. As I said in the beginning, sometimes the darkness is beautiful; and, sometimes the darkness makes us beautiful.

There’s many a burden to be borne in this business; which is why I have to remind myself of the reasons I remain a funeral director.

5 Benefits of Educating Yourself About Death in Your 20’s

Today’s guest post is written by Michael Perice

Death is scary, and even members of society with requisite training and experience (including funeral directors, therapists, and clergy) sometimes have trouble processing the death of a loved one. So, why should people in their 20’s take the time to educate themselves about death? I mean, who in their right mind would ever want to sit around and think about dying! That’s so… depressing! Yet, countless studies have shown us that the benefits of death education far outweigh any associated taboos or negatives. Whether you do a quick Google search, buy a book, or speak with a professional, the benefits of educating yourself about the process of death is important, and it can help in ways you probably never imagined.

So, why don’t young adults take the time to learn about the process of death? Well, to put it simply, they’re scared shitless at the prospect of facing their own fates. After all, they’re a part of the demographic known as the invincibles- you know- the generation of young adults who perceive themselves as being immune to sickness or injury, and surely they don’t need to go any further and think about that “scary thing” that happens when you get older. In fact, if you asked someone in their 20’s what he or she thinks about death education, they would probably say something along the lines of, “OMG ewww nooooo!” Or maybe a simple, “wooooooah.” Well, listen up 20-something’s: electing to ignore something as impactful as death is not a solution, and as someone who has officiated, managed, and attended funeral services, believe me when I tell you, you need to be able to comprehend the incomprehensible, or at least start thinking about being able to process the inevitable.

Here are 5 benefits of educating yourself about death in your 20’s:

1) Being prepared can help ease a painful process and move you towards healing

This is an easy one. If you had a final exam or an important work assignment, you would take the time to study or prepare in advance, right? Well, the same concept applies when it comes to preparing for the loss of family or close friends. Though the death of a loved one may seem uncommon for people in their 20’s, in fact it is typically the period during which young adults will lose a grandparent. Being prepared can reduce the fear, anxiety, and confusion that usually accompany the death of a family member. Don’t get it twisted, the death of a family member can (and probably will) disrupt your life, but being entirely unprepared for that experience can have lasting effects for people ill-equipped to handle such a traumatic event. By taking measures and readying yourself for the inevitable, you’re replacing all the unknowns that come with losing a loved one, and this helps to begin the grieving process.

2) Being a better friend and a more empathetic person

Taking care of others, helping someone in their time of need– sounds like being a good friend, doesn’t it? Yet, how many times has a friend or a co-worker opened up to you about the death of a loved one and you simply didn’t know what to say? In fact, your silence might even be considered apathetic, when in truth, you were probably just scared. It’s a natural impulse to try to avoid risky interpersonal situations, and that’s how many young adults view discussing death, as a risky endeavor. Everyone fears sounding stupid, and the last thing anyone would ever want to do is upset a friend who is already grieving, but it doesn’t have to be like that. By taking the time to educate yourself about death and the grieving process, not only will you be in a position to be a better friend to those close to you; you will be a more empathetic person in general.

3) Appreciation for what you have before you experience loss.

The notion that actively thinking about death can help you appreciate and value life is not a revolutionary concept. As humans, we tend to cherish the things that seem most precious to us. German philosopher Martin Heidegger wrote about how death awareness (the “nothing”) enables us to shift to a mode where we simply appreciate that things are (the “being there”), as opposed to worrying about how or what things are. But you don’t need a dead German philosopher to tell you what you already know, so allow me translate that quote into the language a 20-something might understand— YOLO!

4) Building a sense of spirituality to help cope with life’s difficulties

More than ever before, young adults identify as being “spiritual” rather than religious in the traditional sense. Life without spirituality can be like a glass with no bottom: no matter how much you pour into it; it all comes out the bottom. You don’t need to be a theologian to understand that thinking about mortality-related issues can raise all sorts of “big picture”-type questions about life. Adding spirituality to one’s life helps build a foundation, a bottom to the glass. Individuals who value spirituality take the time reflect on their lives, and eventually on their deaths.

5) Dealing with fear in a productive way

I’m not going to quote Roosevelt here, but you get my point. Living a life full of fear is not living a life at all. So many times I’ve heard young adults refer to the death of a loved one as “passing on”. Though that choice of verbiage may seem insignificant, it seems to be representative of a deeper, more fundamental problem: if young adults can’t even say the word death, how are they ever going to ever face it in their own lives? Like any fear, it can be rational and still be unhealthy, but regardless, it can be overcome, and all it takes is a little time for discussion and education!

*****

About the author: Michael Perice is a rabbinical student at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in Wyncote, PA. He is currently the Community Outreach Director for Goldsteins’ Rosenberg’s Raphael Sacks, a fifth generation family business, and one of the largest privately-owned Jewish funeral homes in the Northeastern United States. Michael’s ultimate dream is to become a “new” kind of spiritual leader for the next generation of young adults.