On Sharing the Silent Grief of Miscarriage

Miscarriages cause a silent grief. A nameless grief. Often a disenfranchised grief.

A grief for one who had no connections in life. No schoolmates, no friends, no co-workers … all of which translates to no funeral. A grief that can’t be shared.

A grief to be borne solely by the ones who conceived. A grief that is carried by the one who may now feel guilt upon silent grief because she miscarried.

This is a grief that is often carried alone. A grief that is too often complicated by guilt. A grief that is private and difficult to share. A grief for a nameless soul.

*****

© 2010 Konstantinos Koukopoulos, Flickr | CC-BY | via Wylio

I’ve seen all too many women (and some men) try to be strong after a miscarriage only to find the grief manifest itself over the next couple months and even years. This is a very real grief and it’s not to be brushed aside.

It’s often traumatic.

Often bloody. Painful.

Often lonely. Powerless.

I remember a bible professor express the need for prayer to my class because his wife had just miscarried. Despite the fact he was asking for prayer, his request was quite smug and short, as if it wasn’t a big deal. Being that my class was a Degree Completion Course, there was a number of older women who quickly asked, “How’s your wife doing?”

He responded, “Oh, she’s fine. It’s not a big deal.”

To that another lady quickly rebutted, “It might not be a big deal to you, but it is to her. And if you have that attitude, it will be a bigger deal in months to come.”

Sure enough, she was right as months later the Prof. shared with the class that his wife was suffering from depression and was entering counseling.

The grief from miscarriages is very real and it doesn’t matter what trimester the miscarriage takes place.

“Women themselves will say, ‘How can a loss at 20-plus weeks be the same as a loss at six weeks?'” said Emma Robertson Blackmore, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Rochester Medical Center who has studied moods during pregnancy, post-partum depression and the effects of miscarrying. “But research says the level of symptoms and impairment is the same.”

*****

Over the course of my 10 years in funeral service, I’ve seen the parents of a miscarried / stillborn child do two things that seem to be very healthy:

1.) Name their child.

2.) Plan a funeral for their child.

I have to admit that the first time I worked a funeral for a couple that miscarried, I thought it wasn’t worth my time. But that all changed when I saw the utterly disheartened grief on the face of the mother and expecting father. They were devastated.

We performed most of the services for free, and I imagine most funeral homes do the same, but honestly, especially for miscarriages, there is no need for a funeral director, but there IS a need for a gathering with your closest friends and family … those who love and support you … to express their love for you. It’s one of those seemingly selfish things that’s entirely unselfish. Because it’s a time for others to recognize the loss, grieve with you and have an opportunity to pour out their love for you.

Name the child.

Don’t let the child be nameless. For both the child’s sake and for your own sake. Name the child so that you can have a more defined grief process.

And even if the the child was miscarried years ago and you suffered in silent grief … it’s never too late.

Even if it’s just you and your spouse, or you and a close friend, have a small service where you remember and reflect on your hopes and dreams for a future that ended too soon.

Grief shared is grief diminished. It’s time to share.

And it’s time we take miscarriages / stillbirths very seriously.

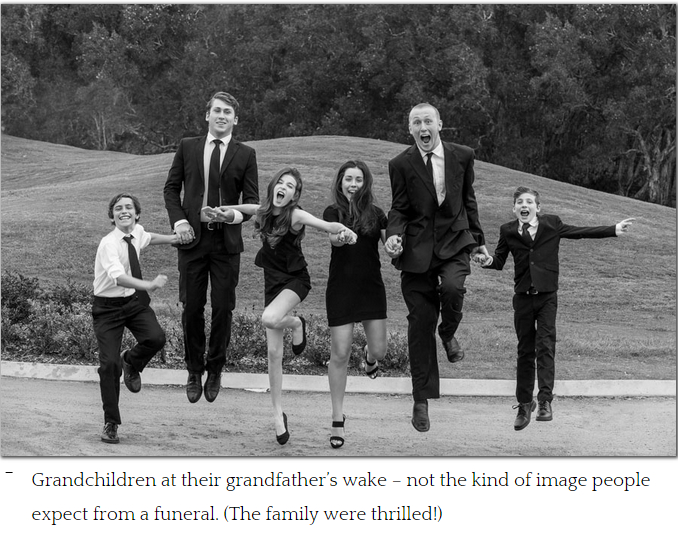

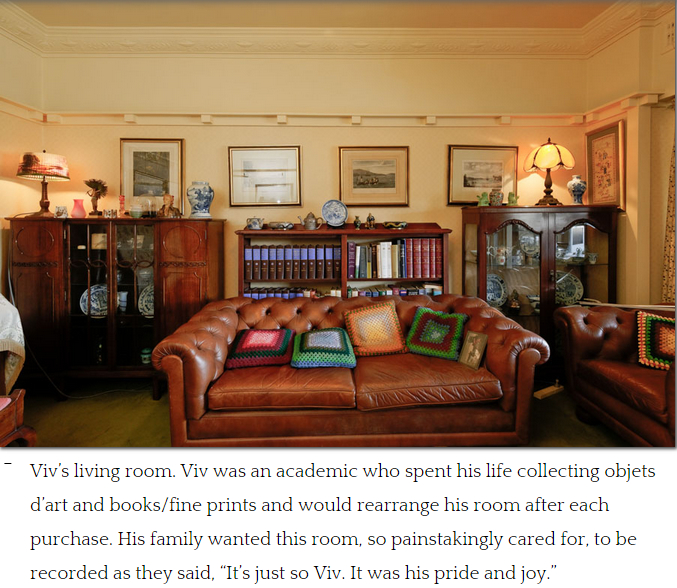

What funeral photography is about: 5 steps

Today’s guest post is written by Australian funeral photographer John Slaytor:

When I tell people I’m a funeral photographer they can be slightly taken aback. They remove “funeral” from the occupation and replace it with “wedding”.

They think, “How can you be a photographer at a funeral? How can you ask people to smile?”

Well, that’s not quite the point. And here are 5 (there are heaps more) points I’d like to share about being a funeral photographer. It might not be what you first imagine!

ONE. A funeral photographer isn’t a wedding photographer!

When a wedding photographer turns up at a wedding everyone knows what to expect and how to behave. When I turn up at funerals people don’t know what to expect. They’re not in a familiar situation and didn’t expect a photographer to be present. There’s no protocol with a funeral photographer so once they’ve seen you they tend to ignore you. You thus become invisible and it’s at that point that you can take really good photos.

TWO: Discretion is key to funeral photography

As you move around discretely, you can capture love, tenderness and genuine emotion. No one is performing for the camera. You also do have images of people smiling and laughing, it’s not all blubbering and red eyes from weeping, as people so frequently imagine.

THREE: As a funeral photographer you get to capture tenderness

At funerals people are at their most human and it’s this that I love capturing.

I’m interested in people’s humanity. Capturing tenderness. It’s the emotion that people give to each other that is the most moving.

FOUR: As a funeral photographer you’re enabling people to grieve

You perform a service. You’re recording a gathering of people who’ve loved the deceased and it’s that love that you’re capturing. You’re giving them something that they can remember and look at and see a family/friends united. So you are preserving the memory of a person.

FIVE: As a funeral photographer you’re giving something tangible to preserve memories

In the west we’ve dispensed with death. The reminders of death (gravestones) are diminishing. Photos are one of the few ways left of preserving that memory by something tangible.

*****

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: John Slaytor has photographed funerals since 2007.

A professional photographer, John Slaytor’s photography has been purchased by Australia’s major institutions including the National Portrait Gallery, the National Library of Australia and the State Library of NSW.

An acclaimed photographer, John Slaytor has been in Australia’s most prestigious photography competitions including the National Photographic Portrait Prize, the Olive Cotton Prize and the Moran Photographic Prize.

You can visit John’s website by clicking the link: thefuneralphotographer.com.au

“Your scars are beautiful”: A guest post on self-harm

Good writing happens when you are whisked away from your own reality and placed into another reality. It happens when someone else’s narrative becomes apart of your own.

Valuable writing happens when you’re whisked away into a perspective that you don’t understand. It happens when you begin to see multiple dimensions of a narrative you previously saw as one dimensional.

The following guest post by Jocelyn Ressler is that rare piece of writing that’s both good and valuable.

***Trigger Warning***: If you’re sensitive to writing that deals with self-harm and suicide, please don’t read this article.

Do not tell me my scars are beautiful

I did not do this to myself to look beautiful

To appeal to some fucked up

perception of what beauty is

What scars are

What scars represent

Was I beautiful when I was biting my lip

pressing scalding metal to my flesh?

Was it attractive when my mom laid me down on the floor

blood pumping from my arm

the day I went too deep?

Would you tell me I’m beautiful if I didn’t have scars?

Would you have looked twice at me

without the crisscrossing white lines

and the purple blotches?

Wouldn’t it be sad

if the most beautiful thing about me

is the hate that I carry on my body?

“Scars are tattoos with better stories”

Better stories?

Better for who?

Nobody looks at my arms and sees

a good story

A good time

A good memory

Looking at myself

I read the stories

Stories of chaos

Stories of pain

Some marks I remember making so clearly

Others are a mystery

Some of the lines spell out thoughts

Short blurbs of my conscience

“Dad”

on my calf

next to

“Goodnight”

“Whore”

across my chest

“Die” or “Death”

many times

“Fat”

on my stomach

“Get out”

on my right thigh

“23”

on my left

“Rape”

on my arm

and ironically

the biggest

“I know better”

on my leg

Looking at my tattoos

I see the stories there too

Stories of hope

Remembrance

Influence

So tell me

How are scars better stories?

Are they preferable?

Desired?

I’d rather hand over some cash

for an inked man to press needles to my skin

Than give up my life

to take a razor to the same skin

“Never be ashamed of your scars”

Am I to be proud?

If I had harmed anyone else

the way I harmed myself

would you tell me

not to feel remorse?

Why wouldn’t I be ashamed?

I am living on the border

of a society that glorifies my behavior

and a society that condemns it

But neither

will ever understand

“Maybe you should cover your arms; kids will be there.”

“Are you emo or something?”

“Cookie cutter.”

“Why haven’t you just killed yourself?”

“You’re cute. Messed up skin kinda doesn’t help you though.”

“What are you going to tell your kids?”

“Ew.”

“Why are we on a team with the emo girl?”

“Stop trying to get everyone’s attention.”

“Why are your sleeves rolled up?”

“I wasn’t going to tell you, but that looks really ugly.”

“You’re wearing a jacket to homecoming, right?”

And today in a coffee shop:

“Have some self-respect.”

Please read Jocelyn’s most recent piece, “Frozen in Time.”

Why Funeral Directors Become Narcissists: Seven Reasons

There’s a fine line between being a funeral director and being a narcissist. We’re called to be directors, to display confidence, knowledge, authority and strength during people’s weakest moments. But this environment that asks us to lead can too often enable us to self-enhance. We talk over our heads, project authority in situations that are best left to the family and tense up in disdain whenever we’re questioned..

Unfortunately, many funeral directors become narcissists (the funeral industry also has a tendency to harbor narcissists who gravitate towards the pomp and professionalism of funeral service). And while it would be easy to simply call these guys and girls “jerks”, the situation is usually more complex. For many, the tendency for funeral directors to become self-absorbed isn’t a product of nature, but of nurture. And recognizing the environmental factors that produce narcissism in funeral directors is a big step in making sure we keep focused on the heart of the funeral industry: serving others. Here are seven factors that tend to produce narcissism in the funeral industry and therefore keep us from being the public servants we’re called to be.

One. Power.

Families come to us in despair, their minds clouded by grief and the unknown. They pay us to be the stable minds. And they give us power. They give us power every time they trust us with their deceased loved one and their grief. And when they give us that power, there’s a certain satisfaction that comes with treating that vulnerability with as much honor as we can.

But sometimes that power can bloat our egos.

Two. Praise.

Being told, “You’ve made this so much easier for us.” or, “Mom hasn’t looked this beautiful since she first battled cancer”, or “You guys are like family to us” means a lot to me. It’s important to know that what we’re doing is meaningful for the person we’re doing it for.

That verbal affirmation is a big reason why I continue to serve as a funeral director.

But that praise doesn’t mean we know it all. It doesn’t mean we’re never wrong. And it certainly doesn’t mean we’re the unquestioned authority on all things funeral.

Three. Pomp.

We get up in the morning, put on our nice clothes, park in the parking lots of our grandiose funeral home and pull out our grandiose Cadillac and Lincoln funeral coaches. Pomp has a tendency to make us think we’re important and to make us forget that all that pomp isn’t for us, it’s for the family we’re serving.

Four. Lack of Criticism.

So, when people ACTUALLY do question you, when your beliefs are questioned and when you’re criticized, it’s important for us to remember that we’re here to help families, not give them all the answers. Our pride isn’t in ourselves. Our pride is in service; and criticism — as hard as it is to hear — is often a very healthy way to enhance our understanding of how we can better serve.

Five. Secrecy and Professionalism.

Leon Seltzer writes, “(Narcissists are) highly reactive to criticism. Or anything they assume or interpret as negatively evaluating their personality or performance. This is why if they’re asked a question that might oblige them to admit some vulnerability, deficiency, or culpability, they’re apt to falsify the evidence (i.e., lie—yet without really acknowledging such prevarication to themselves), hastily change the subject, or respond as though they’d been asked something entirely different.”

The secrecy (which is often clouded in a pretentious form of professionalism) of the funeral industry often allows an out for narcissists. If their work is questioned or criticized, they will often pull the professionalism card

Six. Micro Markets.

There’s nobody that knows the people in your community better than you. You are the best person to serve those that walk through your door. YOU have poured yourself into the community, you have give your holidays, your late nights, your overtime for people. And sometimes we feel like we know our market so well that we know it better than the ones we serve. I’ve seen it happen. You may have invested decades into your community, but that doesn’t mean you these are “my families” and “my people.”

Seven. Education.

In a culture of death denial, we are one of the few segments of the population that think about death on a regular basis. And in a culture that rarely thinks about death, it doesn’t take much knowledge to feel like a “death expert”.

Let’s just make a couple things clear: funeral directors aren’t psychologists, we aren’t philosophers, we aren’t grief experts and because there’s such a vast array of funeral customs and practices, we aren’t even funeral experts. Sure, you know your demographic, but your demographic is a very small sample of global funeral customs. Narcissists have grandiose sense of self-importance and often times this leads to funeral directors thinking they are the end all be all of death education.

When You Can No Longer Visit the Grave: A Story of Child Loss

Today’s guest post is written by Janie Garner

When my son was killed at 17 years old, I knew I would visit his grave a few times a week for the rest of my life. This was an obligation. Not visiting him would be tantamount to neglect. These were my son’s bones, all that was left of him on the earth. Someone had to visit and remember, and it was my responsibility.

I haven’t been in almost a year. He died almost 4 years ago.

The first several times I went, there was no headstone yet. I am a Navy veteran and Alex, as my minor child, was entitled to be buried in a national cemetery. I went and looked at the fresh dirt with orange plastic netting on it, to prevent the ground from eroding. I looked at the printed card and metal stake. It was winter. I sat or sprawled on the grave for hours at a time, until my hands turned blue with cold. We had an unusually snowy winter. I sobbed and tried to bargain with God to take me instead. As you can see, that didn’t work out for me. People came over and asked me if they could call someone, and if I was ok. I must have been quite a spectacle if strangers were that concerned about a woman crying over a fresh grave.

I wanted to say: No, I am not ok. You are a well-meaning but stupid human. Get away from me. Can’t you see I am trying to mourn my kid, or freeze myself to death? Instead, I said “Thank you, I am fine “.

Then it became spring and I showed up several times a week to watch the plugs of grass spread across the hole. The netting was taken away at some point. The stone was set, and I spent hours tracing his name with my fingers, and punching myself in the leg as hard as I could to distract myself from the psychic agony I felt.

The first time I saw his name (and mine) on that headstone, I screamed and fell to my knees. It was so much more permanent than the card and the stake. The US Government had provided a monument that said he was dead forever. It was lined up with thousands of stones exactly like it. There was an empty space next to his grave, for my husband Paul, an Army veteran. I would be buried on top of my baby. My name and pertinent dates will be carved into the reverse of his stone. Our various atoms will perhaps eventually mingle again, as when I carried his body inside of mine.

His bones are in the company of heroes. The national cemetery will be perfectly maintained for as long as the US Government exists. There are literally hundreds of deer, completely unafraid of humans. They walk among the monuments peacefully. They also eat the flower arrangements. Alex would enjoy that.

Six months passed. I found myself dreading each visit. They spread further and further apart. I became completely hysterical and inconsolable during and after each visit. I was guilty for not going as often as i should. I became mildly suicidal every single time i visited. There was no winning this one.

My Father-in-law was diagnosed with terminal cancer when Alex had been dead for 10 months. He was dead a month later. He mentioned that it was too bad that he couldn’t be buried next to Alex, his much-loved Grandson. I am the nurse in the family, so i took care of him. He died at home, with us.

Naturally, when he died we gave him my husband’s spot. Paul will be buried with his father, a decorated Purple Heart and Bronze Star Vietnam Veteran. I will be buried with our son. We have created a family plot in the middle of a National Cemetery.

Alex’s grave was disturbed when they buried his grandfather. This caused me to be unable to leave my bed for weeks. The grass took some time to grow back, and it became my habit to lay in the dirt and/or mud between them, with one hand on each grave. This winter wasn’t as snowy, but it was wet.

If I was mildly suicidal before, now I was in great danger of ending my own life. I started only going on holidays, birthdays, and death days. This made me less suicidal, but more guilty.

I felt like I was failing to properly honor my son. I still do, but I cannot take the emotional tornado caused by seeing my baby’s name on a headstone twice a week. I was dying inside a little more each time I visited. I have the florist deliver flowers to the graves occasionally. Other family members visit sometimes, and I know the cemetery is cared for. I can do nothing else. I have nothing left to give.

I feel like the custom of visiting graves is barbaric, at least for grieving parents. There is nothing under that stone but a decomposing body. In this case, the body of the child who was NEVER supposed to die before me. The body that died and completely invalidated my life, The body I didn’t protect well enough.

The body I failed.

Because that’s really what the problem is. No matter how many times you tell a grieving parent that their child’s death was not their fault, they will never believe you. Somehow, in their own minds, they are to blame. My son was killed when he was hit by a 9 ton tow truck, operated by a distracted driver. I was 40 miles away. I blame myself.

So visit if it comforts you. Do not visit if it tortures you. Your kid doesn’t care. Either the Atheists are right and he knows nothing about it, or he is in Heaven and way too busy partying it up with God to notice worldly stuff.

At least, that’s what I tell myself.