Miscellaneous

Unable to Say a Last Goodbye: A Guest Post

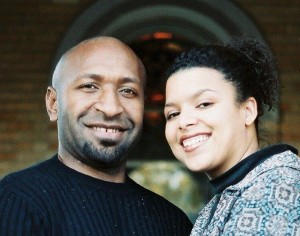

Today’s guest post is from Pastor Melanie Thirion. Melanie lives with her family in South Africa. She tells me that English isn’t her first language, but she writes better than I do!

Here’s her bio: I am a follower of Christ, a wife to a very humble man named Christi, who happens to be a minister too (another story for another day). I am the mother of a spirited angel called Caro. I’m a youth minister in the Dutch Reformed Church, Kenridge congregation to be exact, in Cape Town, South Africa. I am also a part-time lecturer in Practical Theology (youth ministry) at Faculty of Theology, University of Stellenbosch.

*****

In the first congregation where I ministered, I made a friend that was much older than me. She was a wise woman, someone who had a strong sense of justice and lived closely with Christ. She had a servant heart. While her children were part of the youth ministry, she and her husband were committed to the ministry, always driving lift-less teens to church (the age for a drivers licence in South Africa is 18 years), taking in troubled teens, showing them that loving parents still exist in this day and age.

When my baby girl was born, she looked after her when I had to return to work. I never had to consider day-care for my baby, she took the responsibility. Probably the best gift she could have given me and my girl. Since my parents, as well as my husband’s, live far away, she was my baby’s grandmother. Her house is the first place my baby slept right through the night. I believe she poured wisdom and love and grace into my girl’s life.

I then changed congregations, but still drove 20 minutes, once each week, for my little girl to visit my friend.

She became sick with bone cancer about two years ago. The chemo seemed to work and we all prayed that she would heal, as she had overcome breast cancer about 8 years ago. But once the cancer spread to her organs, I knew it was just a matter of time. Three months ago we had a heart breaking conversation when she told me she couldn’t look after my girl anymore. It was a very difficult decision for her to make, as this, for her, marked the beginning of the end. During our conversation, I went into minister-mode and seemed alright with her decision, numbing my emotions as just ministers can do in emotional-laden situations. I was in denial.

Then, the second week of December, we skipped our weekly visit to my friend. I can’t even remember why. And the week after that my friend was in the hospital and her liver failed. I thought I still had time to visit her, to say goodbye. So the next morning, I organised my schedule so that I could go to the hospital early afternoon. When I got into my car to drive to the hospital, her daughter texted me: “Mom just died.” I was too late. And hated myself.

I had a hard time forgiving myself for being too late. Which is kind of self-centered I know. As a minister I know that I shouldn’t beat myself up about that. As with birth, death has a time of its own – independent of anyone’s schedule or preference. But I did beat myself up, a self-directed tantrum. I wanted to say goodbye, I wanted some more time with my friend. I wasn’t ready for her to die. But, as with all the kingdom of God, it’s not about me…. My friend was ready to die. And she did. Although I was disgusted with God.

I found comfort on the day of her funeral. The minister shared with us how we now have a friend among the cloud of witnesses Paul speaks of in Hebrews 12. This scripture, not a typical funeral text, comforted me, and re-affirmed eternal life for me. The thought of my friend being amongst the great faith heroes, where she rightly belongs, gives an eternity to her legacy. I also had the opportunity to spend a minute alone at her coffin, saying goodbye. But the journey did not end there.

I still had a little part of grief that needed to be aired. I took to my paint brushes and painted something that will always remind me of my friend, but also of my God who comforted to me through his Word. Just take note that I am in no way an artist. It’s just the way I deal with emotions. And grief.

Rest in peace my dear friend. For I know that God is with you.

Attached is a picture of the painting I made, drawing inspiration from Hebrews 12:1-2.

Finding a Context for Grief: A Guest Post by Jason Hague

“Jason, listen. I think I found a lump.” Karen’s eyes were full of gentle severity. “But hey, we’re okay. We’re gonna get through this. It isn’t our first rodeo.”

Karen was too young for cancer—just thirty four—and full of life. She and her husband George had been my friends for nine years, and part of my family for the last five. They were missionaries, planning to launch out to the South Pacific to eventually start an AIDS orphanage. And after countless encouragements, they believed with all their hearts that she would be healed. After all, she had beat cancer before when she was seventeen, and again (we thought) at thirty-two. That’s why she was so confident.

So they entered the rodeo a third time, pursuing all kinds of treatments; the ones that come from sober doctors in white hospitals, and the other ones from enthusiastic Americans with juicers in Mexico. They got prayer. Lots of prayer, from reserved, gray bearded conservatives, and from young mustached mystics who claimed they saw miracles happen every day.

They went on like that for months, traveling the country, raising funds for their move to the islands, all the while believing against the obvious. She was getting weaker. And weaker.

I got the call while watching a college football bowl game. Karen had collapsed and had a seizure. She was in intensive care. Even brain now, it seemed, was being squeezed by cancerous masses. The doctors were saying it was time.

Before I got in the car for our five hour trek to the hospital, I had an awkward stare-down with my pinstriped suit. As a rule, I don’t wear suits except for mandatory formal occasions. I knew the odds this time. But if I took it… what would that say about my level of faith?

I remember stomping out of my bedroom, tears shaking me from the inside. “Fine, God. I’m leaving the damn suit.” I said aloud. It was as much belief as I could muster in that moment.

Four days of blur followed, and finally, our remaining hope disappeared with our emotional strength. The nurses—Lord bless them—let me sneak my daughters into the ICU to say goodbye to their adopted auntie. She was too weak to say anything, but she hugged them limply. And to each of us, her circle of friends who had become kin, she spelled out farewells on a whiteboard full of letters.

I was in the room when her breath ran out. George was still embracing her, still serenading her body. “You are so beautiful to me.”

I would need my suit after all.

They wanted me to do her funeral, but I just couldn’t. All I could muster was a couple of weak stories about being together, watching Jack Bauer and dreaming of all the exotic ministry we were going to get to do one day. It all seemed so empty. So hollow.

I told God how much it hurt. I didn’t blame Him for her death, but I thought it was a pretty low thing of Him to do, giving words of hope when no hope, in fact, remained. God didn’t answer much. He mostly just listened. I don’t think He ever got offended by my doubts, or my cursing, or my anger. Wasn’t it Jesus, after all, who said to weep with those who weep?I wonder if you can’t talk someone out of pain, even if you’re God.

But eventually, I knew I had to make a decision. I could hold onto my complaint against Him, but only on one condition: I had to first acknowledge His generosity. He had given her seventeen years before she met cancer, then seventeen more after that. He gave her life. Karen was His present to all of us. And in this age, there are no presents that last forever.

So I made a decision to look God in the eye again and thank Him for my friend. This wasn’t so much a matter of religious sentiment as it was intellectual integrity. When gratitude is absent, mourning eventually loses all context and reason. It’s the same lesson I try to give my kids: to say “thank you for my ice cream” instead of pining hard for a second bowl. Even a gift cut short is, first, a gift.

Looking back, I see my own tears had testified of my great privilege: Karen was so lovely and gracious and warm, and I had been her friend. Her brother. Little did I know, my grief was itself building a case for the love and graciousness and warmth of her Maker.

And it made me look forward to the next age, when the Good and Perfect Gifts of our Father will indeed go on and never expire.

*****

Jason Hague is a pastor, writer, and former Youth With A Mission teacher who lives in Oregon with his wife and five Children. He tells honest stories of faith, culture, and autism at JasonHague.com.

You can follow Jason on Twitter and like him on Facebook.

Owning my Grief after Three Miscarriages: A Guest Post

Miscarriage is a silent grief. We don’t understand why it happens. We don’t know how to talk about it when it does. Through my experience of three miscarriages and three healthy births, I am slowly learning to speak. Here is part of my story of learning to redemptively own my grief, and, in doing so, to try and offer comfort when others grieve silently.

Healing through words

Writing in my journal shaped my encounter with the miscarriages. I initially viewed our first miscarriage in 2004 as my wife Kristine’s loss, because she endured the physical trauma. Journaling about the miscarriage helped me acknowledge the hopes and fears of parenthood that I had held for our child. As I continued writing, I claimed each miscarriage as my own loss. I also claimed my identity as a grieving father, and Kristine’s identity as the mother of my children.

Writing about my confusion and grief enabled me to mourn the awfulness of your death. Not as an angry shout at the futility of life in a world that burned me one too many times. Nor as blind acceptance of actions from a distant God whom I’ve no right to question. But to acknowledge the loss of a life I was growing to love, the end of a journey that hardly had a chance to begin, the absence of a relationship I was looking forward to entering.

That lament created space for me to honor the value you brought to my life, verbalize the pain of your loss, and express the confusion of trying to come to terms with a side of life I didn’t expect to encounter. Talking about how I cried for you, for what you would bring to my life, was infinitely more valuable than finding a cure for the pain of your death.

I think I felt like I had paid my dues with the first miscarriage. Our second miscarriage forced me to face the possibility of never having children. During that time, I grappled with the symbol of the open hand, which had been foundational in my relationship with Kristine. I knew I must love her unconditionally, even though that would let her hurt me. I knew conceptually about loving my living children with the same open hand. I had never considered extending that open hand to a child still in the womb.

I had to decide whether to protect myself from being hurt by another miscarriage, or to voice my love for a child I might never meet. I also had to decide if I would extend an open hand to Kristine, who I resented for responding to the miscarriage differently than I was. Journaling helped me acknowledge the hope for my child’s life that was hidden deep beneath my cynicism about the miscarriage. I modified Albert Brumley’s hymn If We Never Meet Again as part of a liturgical farewell to my child.

Now you’ve come to the end of life’s journey. It turns out we’ll never meet any more, ‘till we gather in heaven’s bright city, far away on that beautiful shore. … Since we’ll never get to meet this side of heaven, I will meet you on that beautiful shore.

Farewell, Child, until we meet face-to-face for the first time. Go with my love. Dad

Healing through songs

The first miscarriage shocked me. The second miscarriage shattered my worldview. The third miscarriage brought me to despair. When we decided to try and get pregnant a fifth time, I let myself hope for new life in ways that I hadn’t when our daughters, Elise and Charis were born. I felt like that hope was thrown back in my face when we miscarried a third time. I wanted to give up completely on my hope for new life, and on the work Kristine and I had done to grieve together instead of alone. It hurt too much. I wanted the dreams to die.

I rarely write music but occasionally I have responded to turmoil in my life through music. The third miscarriage was one of those times. I arranged three texts from Celtic Daily Prayer into a song called The Caim Prayer. The song has two themes: The first is the cry that God would “lift me out of the valley of despair” that I entered when our child died. The second is asking for God’s leading “along a path I had never seen before” so that our dreams would not die.

Kristine and I also compiled about thirty songs – some individual favorites, and others that we listened to together. Expressing our pain, despair, and confusion to each other through these songs helped us to grieve both alone and together.

Healing through images

The crocuses in our yard comforted Kristine after our first miscarriage. Like our unborn children, they are precious, beautiful, and alive for only a brief time. When we commissioned Indianapolis artist Kyle Ragsdale to paint our family for our 10th wedding anniversary, Kristine asked him to include a crocus for each unborn child. In many ways, that painting represents our hope for the miscarriages to be part of our lives … not as a dark blot in the center, but nevertheless woven into their creative fabric. Much of that hope is articulated in a letter that I wrote to all my children.

The crocuses in our yard comforted Kristine after our first miscarriage. Like our unborn children, they are precious, beautiful, and alive for only a brief time. When we commissioned Indianapolis artist Kyle Ragsdale to paint our family for our 10th wedding anniversary, Kristine asked him to include a crocus for each unborn child. In many ways, that painting represents our hope for the miscarriages to be part of our lives … not as a dark blot in the center, but nevertheless woven into their creative fabric. Much of that hope is articulated in a letter that I wrote to all my children.

All six of you walked an uncertain road with me as you have borne my burdens through the words of these letters. You will walk that road with me into the future. My unborn children, each of your presence in our lives continues to shape how your mom and I engage our world. You have challenged us to grant you dignity, and encouraged us to not let your deaths be the last word. Elise, Charis, and Clare, you are calling us into the joy of making new life grow. You will learn with us what it means to remember your three siblings, to live with open hands, and to see and speak peace into humanity’s wounds. So we will walk together, until the day when we all meet for the first time.

*****

About the author: Dr. Shawn Collins grew up in Kenya as a missionary kid. This cultural diversity built a foundation that influenced his faith and vocation. His work in the aerospace and energy industries integrates graduate degrees in mechanical engineering and anthropology. He regularly writes and presents on a variety of systems engineering, organizational behavior, and theology topics. Shawn lives in Indianapolis with his wife and three living children.

More information about Shawn’s book Letters to My Unborn Children is available online at www.letterstomyunbornchildren.com. It can purchased there, from Kirkhouse Publishers, or from Amazon. The ebook can be purchased from MemorEmedia.

They Say That Time Assuages: A Guest Post by Tess Pope

About Tess: I am a professional freelance flutist in Boston. My favorite gig in town is playing with the Boston Ballet pit orchestra! Thirty years after graduating from The Juilliard School with a BM and MM in music, I am taking classes once again and thinking about returning to school for a Ph.D; something that will blend my interests at the intersection of the brain, the mind and the spirit and that can have some impact on the welfare of children. I am the mother of four children (two sets of twins). My youngest son, Hunter, died suddenly of myocarditis (a rare virus attacked his heart). We are bereft, yet still, we continue.

*****

They say that time assuages

Time never did assuage

An actual suffering strengthens

As sinew do, with age

Time is a test of trouble

But not it’s remedy

If such it prove, it prove too

There was no malady. — Emily Dickinson

*****

At night, when everyone else is sleeping, and I am lying awake, unable to sleep, and unable to think and unable to remember, I go through my catalogue of memorized poems and “work” on them. I parse out their meter, rhyme scheme, meaning – and use thinking about them to keep myself from thinking. If I search through my memories, or allow the longing for Hunter to speak itself in my mind, then I am done for. There will be no sleep, only this stretching out of time, and a kick in my gut of what I can only describe as ‘horror’. It is a feeling so physical, and so utter and the pain that follows is also so physical and utter that I feel I have to STOP. My head and body ache, like a full body migraine – one part wanting the memories and images of my boy, and the other part in such sharp pain that everything closes down. And so I abandon the attempt again.

Time is always on my mind. What does it mean to be ‘in time’? Does time exist? Or is it a construct for finite minds? “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.” What does it mean to be ‘outside time’? And is that where Hunter is? I spend all my time reading about quantum mechanics and it’s implications from the viewpoint of various physicists. I read about Godel and the idea of a “World Without Time”, about mysticism and mathematics – “The Loom of God”. And what it really comes down to is this “I want my boy back.” And I agree with Emily, time never did assuage. I can’t bear to hear people talk about time and it’s healing properties. Time cannot heal. Only ‘outside time’ can heal. Because the only healing to be had is in connection. “Only connect.” And he is not here. He is outside time.

When people speak of healing I think they mean that the pain will become bearable. But the word ‘healing’ is so deceptive. It is not like a cut where the skin will knit back together, or a rash that some salve can heal. This is loss, – it is an amputation. The site of the wound may heal, but the limb will always be missing.

Also, what would it mean to “heal” from the loss of one’s own child? His cells are still in my body, from before his birth. They were so hard won, these children. Twenty years earlier and I never would have had them. I used to say “They will never wonder if they were wanted. I have the medical records to prove it.” And the misery and sickness of the pregnancies. And the worry, wondering if Molly would even be born alive, with a tumor on her lung. And at every roadblock, we had the best possible outcome. They were all born healthy, and Hunter was even born feet first. He loved how that distinguished him from his siblings. I would tell him the story how after Molly was born, he turned in the womb so that he was breach, but the doctor simply said “No problem! He’s the 2nd twin”, reaching his hand to pull Hunter out by his feet. It was the only birth that brought absolutely no pain, and still all the joy.

More than twenty years ago I went to visit Madeleine L’Engle at St. John the Divine, where she was a librarian, in New York. I lived close by and having read all her books, I took a very deep breath and wrote to her to ask for a visit. It was the most casual thing for her. She was as kind as you would think from her books. But I was still nervous and overly self-conscious and, knowing that her husband had recently died, I said something stupid about death – as if it were a kind of philosophical problem that didn’t really exist. She smiled at me sweetly, (like an indulgent grandmother I suppose) and said “Oh, no. Death is terrible. Death is horrible.” And I understood. Right then, I understood that God hates death. But mostly I remember her calmly smiling at me as she said it. The smile was, in a way, an invitation to wrestle with the hard stuff, – not pass over it with platitudes, or philosophy, or sloppy thinking, – or wishful thinking for that matter. Just like Emily in this poem. Time never did assuage. And I will always want my boy back.

*****

Visit Tess’ blog to read more of her story.

Playing Taps and Doubting God

Today’s guest post comes from Jennifer Lee.

*****

I was a freshman in high school, standing with my head bowed behind the cemetery shed, where the maintenance guys stored the lawnmower. It was noon on a late-winter day, and I waited for my cue, a military gun salute.

I leaned against the weather-beaten wooden planks – hard and cold like my waning faith – while holding a silver trumpet. The family huddled against the wind on velvet-covered folding chairs, under a blue tarp, while the preacher read from a pocket-sized book of last rites.

The uniformed veterans lifted their guns, clicked and fired. Clicked and fired. Clicked and fired.

And I — the lone bugler — stepped from the behind the shed. I lifted the trumpet to my lips to play “Taps” in honor of the middle-aged man in the steel box.

The notes rang out, mingling with pained and muffled cries. And I felt hollow on the inside.

Fourteen years old, and already I didn’t believe there was life beyond the grave. Not for me, or the man in the coffin, or for the hundreds of other sons and daughters already buried here in my hometown cemetery in Iowa — with names like Anderson and Benson and Larson. These were the people I saw in the pews of my church on Sunday mornings. Hear me now: I wanted to believe that there was something More in the great beyond. But it all seemed so … fairy-tale-ish. So foolish.

“Taps,” a song that means “lights out,” was the melodic and literal end of all things. That’s how I saw it anyhow.

Death always exposed my doubt. And from a young age, it came around frequently, like a specter haunting our little Iowa town, robbing me of my favorite people.

When townfolk died, Mom would walk us down the block to the old Sliefert funeral chapel, where our old friends were laid out in velvet-lined boxes. I peered over the edges of their caskets, and when I thought no one was looking, I would reach a hand in to feel the waxy coldness of death. I had once heard that a dead body could actually make a jerking motion, or that its eyes might suddenly fly open, so I’d watch like a tiny hawk, waiting for some macabre spectacle to unfold before me.

Death both repelled and attracted me – the same way I felt when watching horror movies the week before Halloween.

On summer days, my little brother and I would visit the cemetery after the diggers finished making a gaping hole in the earth — before the mourners showed up. Curiosity drew us, and we’d lay on our stomachs giggling nervously as we looked into six-feet-deep holes – dirty holes that swallowed up bodies and precious parts of my faith.

As I grew older, the funeral home director started asking if I’d play “Taps” at the ceremonies of war heroes. The school principal always let me go. He thought it was a “good community service.” But sometimes, I wished he wouldn’t. Sometimes, I’d rather have done algebra, instead of graveside service.

In the cemetery, there was no escaping my own inevitable death. Or my own suffocating doubt.

I played the song — time after time — and it felt like these were the last bitter notes on the end of life.

Casket closed. Book closed.

But right there in the pain of doubt — at the edge of opened graves – I took important first steps in my discovery of life and death and faith in God. I realized that doubt can actually be a gift. No kidding, a GIFT.

It would be years and years later, but I began to ask questions that, ultimately, led to a few important answers.

Here’s the deal: I was a modern-day Thomas. I doubted the very existence of God for much of my life — despite the fact that I grew up among believers, many of whom I led home with a silver trumpet. If there really was a God, I was sure my doubts would doom me.

So I found sweet relief, I tell you, when I found these words in the study notes of my Bible: “Silent doubts rarely find answers.”

That meant it was OK to ask, to doubt, to fumble around for a few answers. It meant that my doubts were not a curse, but a step toward a God who invites us to get close enough to touch a Savior’s scars. He doesn’t turn His back on modern-day Thomases, but invites us closer.

And doubt? Well, it isn’t meant to be a place of permanent residence. Not for me, anyway. For me, it was the place from which I could grow, stepping out from behind the weather-worn shack to play a different song.

*****

About the author: Jennifer is a former news reporter who is passionate about sharing the Good News through story.

About the author: Jennifer is a former news reporter who is passionate about sharing the Good News through story.

She blogs about grace and God’s glory at www.JenniferDukesLee.com. She is a contributing

editor at www.TheHighCalling.org.

You can find her on Facebook here. Soon, her words will make their way into her debut nonfiction Christian book (Tyndale Momentum).