Community

With a Little Help from My Friends

This week my blog is being taken over by Jessica Charles. This from Jessica: I am Corporal Joshua Alexander Harton’s Big Sister. I am his sister and I protected him his whole life. That is until September 18th, 2010 when a bullet from Taliban’s rifle went through his neck, cutting his carotid artery, moving through his torso and destroying organs and finally leaving his body at the left hip and shattering his Kevlar armor. I am Josh’s sister and I need you to know that my little brother is dead and my epic life will never be the same again.

This week my blog is being taken over by Jessica Charles. This from Jessica: I am Corporal Joshua Alexander Harton’s Big Sister. I am his sister and I protected him his whole life. That is until September 18th, 2010 when a bullet from Taliban’s rifle went through his neck, cutting his carotid artery, moving through his torso and destroying organs and finally leaving his body at the left hip and shattering his Kevlar armor. I am Josh’s sister and I need you to know that my little brother is dead and my epic life will never be the same again.

*****

I watch my daughter throw her body down on the floor. She lifts her head to scream and then pounds her hands and feet on the ground. It is a classic tantrum performance. And though she does this act with such precision that I can’t help but want to laugh, I do not. I do not laugh because my daughter is in pain and need and she has no other way of telling me.

I ask her if she is hungry-shakes head no, is she thirsty-shakes head no, does she need to be cuddled-YES.

It seems silly. A cliche event in the life of motherhood but there you have it; a child communicating that she needs help. She doesn’t do it with grace or dignity. She is unabashed at her discomfort with the world and will make sure we all know it. She knows no shame in being upset or sad or uncomfortable. She only knows that IF she shows you she feels bad you WILL help her to feel better.

What a remarkable idea. Telling one another that we feel pain, discomfort and even anguish with the expectation that telling someone will get us HELP.

My brother’s name is Joshua. There are many Hebrew translations of his name but my favorite is “A crying out to G-d”. It is also translated as “Salvation”. The reason for two seemingly dissimilar meanings is clear if you have studied Hebrew (which I have). In Hebrew, often a word means one thing AND its response, or its understood that if in context something is asked it is ALSO replied to. For example, the word SHEMA means “Listen, Hear and Obey” as in “If you were listening to me, you would have heard and then obeyed”. In this way, “A crying out to G-d means that G-d will answer and you will be given Salvation”. Remarkable huh?

My brother did not cry out. Not in his life or at the time of his death. He made his own salvation. He did not like to ask for help but was happy to offer it. When he did ask it was of a very few. Josh would not ask for help unless he thought it was something you could give. I admire that but at the same time, I wonder how much more we could have helped one another if we only knew where to begin.

Before he deployed, I told my brother some things about our childhood. Details he was not previously aware of and they seemed to bring him peace. I wish I had known sooner and been able to tell him. I wish I could have told him how much I relied on him to get through a day, just knowing with him in this world I was never really alone.

Now Josh is gone and I have learned a hard lesson in an uneasy way. I need help, I need it almost daily. I go to therapy and I take medications and I read the books assigned by my doctor but in the end and I mean up until MY very end: I will not get over my brother’s death. I can’t. And that will leave me with a difficult life filled with painful moments, moments which can only be eased if I tell you that I hurt and you give me your aid. I am in mourning which has no end date.

If when I am in pain, if it seems the world is caving in on all sides and I want to throw myself on the ground to scream and hit and kick, don’t laugh, don’t run, but instead, give a little help. Because I get by with a little help from my friends.

*****

You can visit Jessica’s blog at “Always His Sister.” And you can follow her on Twitter.

When Our Memories Smell Like Us

Four months after Newtown, People magazine has published a series called, “Life After Newtown Shootings” where the parents describe their grief and how they are coping. It’s a beautiful series and well-worth your time and the three dollar Kleenex box that you’ll go through.

One of the parents mentions that she still sleeps with her son’s pajamas so that she can be soothed by “his smell.” Certainly, considering the tragedy of Newtown, there is nothing abnormal about her practice. In fact, it’s healthy and I can’t help but feel the heaviness of her grief as I think about it.

Here’s a question: A what point has her son’s smell disappeared and what she thinks is her son’s smell is actually her own smell. At what point in sleeping with his pajamas have they stopped smelling like her son and started to smell like her?

At funerals, you’ll often hear people say, “Cathy lives on in all of our memories” or, “Cathy will never die as longs as we remember her.”

There’s a difficulty that comes with remembering our loved one.

I remember an old man, who was married to his late wife for over 50 years, stopped into funeral home to pay his bill and he said, “I both grieve the loss of my wife and the distortion of my memories of her. Even now, when I remember her, I ask myself, “Is this memory real or is it my mind’s adaptation of her? I only want to remember the good, but I miss the bad and messy nearly as much because it’s who she was.”

There’s a time when the smell on the pajamas becomes our own. There’s a time when memories are distorted by our desires for comfort. But, this is why we must grieve in community … so that community can help us piece together the real.

Grief must take place in community! We have to share, we have to be vulnerable with our friends and family.

Share at your family dinners … over the holidays.

Be brave an ask your parents old friends about mom/dad. Ask your child’s friends … your spouse’s co-workers.

Have people write down their memories.

Talk. Talk. Talk. Talk about your deceased loved one. Don’t let the memories die. Don’t let them become distorted.

Ritual: The Muscle Memory of Grief

Over the past couple months, I’ve been contemplating why the West (America, Europe, etc.) has so much aversion to death, while other — less “developed — cultures see death as less alien. I’ve come up with two major reasons:

One. Modernity.

Our modern world takes death care away from families and puts it in the hands of “professionals”, thus industrializing death. Instead of the dying dwelling at our homes, we give them to nursing homes. For more of my thoughts on this, here’s an article I wrote.

The modern world also likes providing answers to life’s questions. So when death comes with its silence and mystery, we are rendered uncomfortable.

Two. We lack ritual. There’s three reasons why there’s a lack of ritual:

1.) We tend to be individualistic, which isn’t necessarily bad, but it produces a lack of community.

2). We tend to dislike tradition.

3.) We are becoming post-religious.

The following is my (rather poor) attempt to explain why the lack of ritual increases our aversion to death.

*****

Muscle memory is what separates the professionals from the amateurs.

Muscle memory is what enables musicians to thoughtlessly play complicated music with near perfection.

Muscle memory is the product of laborious habit that makes incredibly difficult tasks seem like minutia.

I just came back from indoor rock climbing.

I’ve seen athletic and strong newbies come to the gym and they look like fools trying to climb routes. Falling down on their bums, scraping their arms up and getting all nervous when they get to the top of the route.

Climbing is both strength and technique muscle memory. And while newbies may be strong and athletic, if they don’t know how to move their bodies on the wall, they’re destined to fall and fail.

*****

Grief is similar. The walls of bereavement are very intimidating to even the spiritually and psychologically strong. It doesn’t matter how whole you are, you will fall and you will fail.

Unless you enter through the trodden paths of ritual.

The muscle memory of grief is ritual. Ritual allows us to take the incredibly difficult task of mourning and find a way to persevere, even when it seems we shouldn’t.

Muscle memory is usually something you or I create through practice. I climb routes at the climbing gym, my muscles get used to moving a certain way.

You practice the guitar day in and day out and your fingers move like jazz.

This is where the whole muscle memory analogy starts to fall apart when we relate it to grief.

While a professional’s muscle memory is something he or she created, death ritual muscle memory is something our community has created and it can only be “learned” within community.

You didn’t create it. It’s something we inherit … or something we can join.

*****

This from Alla Bozarth in “Life Is Goodbye, Life is Hello: Grieving Well Through All Kinds of Loss”:

Funerals are the rituals we create to help us face the reality of death, to give us a way of expressing our response to that reality with other persons, and to protect us from the full impact of the meaning of death for ourselves.

The problem is this: so many of us have disconnected ourselves from community, tradition and a religion that we’ve never received the graces of grief ritual.

If we have community in place,

if we embrace tradition in times of death

and we’re willing to involve the motion and movement of religion,

we may find life and meaning in a task that many onlookers see as insurmountable.

Ritual doesn’t allow you to overcome grief (grief may never be overcome). It doesn’t allow you to work through your grief faster. Nor does make death more tolerable. And it certainly won’t make you a “professional.”

Ritual allows you to confront a seemingly impossible task in the context of community.

Why is the West so adverse to death? Because devoid of ritual, confronting death is like asking me to play Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 23.

Yesterday I Saw the Body of Christ at a Funeral …

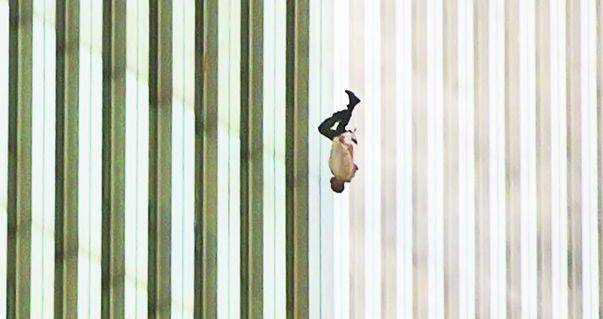

… and I took a picture of it.

There’s only two white guys in this picture: the one is the white pastor who is sitting beside the soundboard. The other is the white Jesus engraved in the stain glass. The rest are African American.

There’s a white Jesus in stained glass because this is a white church, that has had 30 plus pastors in it’s history, all of whom have been white.

And today the church is full of African Americans in a white church for a funeral.

The Mt. Zion AME church is in the process of being renovated. And this week the Mt. Zion AME church lost not one but two of their members.

The Parkesburg United Methodist Church opened their doors, their sanctuary and their cafeteria hall for not one, but both funerals.

African Americans in a white church where the white pastor isn’t in the pulpit, but serving the black female pastor in the pulpit by running the soundboard. In fact, he was serving since 8 AM in the morning when he helped carry the casket up the two flight of steps and into the sanctuary; when he vacuumed the entire sanctuary at 9 AM; extended gracious hospitality from 10 AM to 11 AM; and even organized five members of the auxiliary crew to set up plates and places for 100 plus people for the post funeral luncheon in the cafeteria hall.

This is how unity is supposed to work.

One hundred years ago, this wouldn’t have happened. Fifty years ago … maybe even 10 years ago this wouldn’t have been considered. But today I witnessed it. I witnessed the body of Christ.