Death

10 Ways You Can Be Death Positive

Death positivity is simply embracing that part of ourselves that we so often deny: our mortality. As an extension of embracing mortality, it’s also being willing to move towards dying, death and the dead. By that definition, being death positive doesn’t mean that you wear black all the time and avoid the sunlight at all costs. It doesn’t mean that suicide ideation is your go-to for a good time; nor does it mean that you rejoice anytime and everytime someone dies.

Here are 10 things it can mean:

One. Talk about your dead

I just had a gentleman come into the funeral home to make a payment on his brother’s funeral bill. We were talking about funerals and death, and out of the blue he said, “My biggest fear is that 10 years after I’m gone no one will remember me.” We talked some more and we arrived at the conclusion that the reason we don’t talk about our dead isn’t because we don’t love them, but because we’re afraid it’s taboo to talk about them. But, it isn’t taboo. It isn’t morbid. It’s honest, loving and human. Keep your dead alive by actively remembering them.

Two. Hang out with Older People

The most death positive people in the world are usually those that are closest to death. I’m not against nursing homes or rehab centers. We certainly need them, but the fact that they house the most death positive people in society, thereby cutting them off FROM society, makes it really hard for those of us who are younger to learn from their wisdom and mortality acceptance. Nursing homes are essentially taking much of our financial inheritance, but more problematic is they take our death positive inheritance that should be passed down from one generation to the next, from the older generation to the younger generation.

Three. Go to that funeral

Death creates a hole in our lives and our world. It’s like an earthquake that shakes the world we once knew. Funerals are a time when we can reaffirm meaning, love, community, goodness and even humor. They allow us a space to come together and affirm that life is changed, but it still continues on. Funerals are a storytelling practice that keeps the identity of our family alive even when one of our members has died.

I know. They’re awkward. I’ve been to thousands of them. And it’s easy to find excuses to NOT go. But funerals are one way WE cope and acknowledge death. They are, in their most basic form, a communal embracing of death.

Four. Meditate on Mortality

Buddhism’s contemplation of death is called “maraṇānussati bhāvanā”, or simply “Maranasati” (death awareness). Here’s a little tidbit on a guided mortality meditation from the Kadampa Center:

To generate an experience of death’s inevitability, bring to mind people from

the past: famous rulers and writers, musicians, philosophers, saints,

scientists, criminals, and ordinary people. These people were once alive—they

worked, thought and wrote; they loved and fought, enjoyed life and suffered.

And finally they died.

You can also bring to mind your inheritance, and how you should will “Caleb Wilde” as sole heir of all your cash. Not cats. Cash.

Five. Acknowledge Other People’s Dead

Those older ladies who send out condolence cards on the daily? They’re the OGs of the Death Postive Movement.

A card. A kind Facebook message. A plate of bacon given to your bereaved (non-vegan, non-Jewish and non-Muslim) friends. Saying the name of your friend’s deceased loved one. These small acts go a long way.

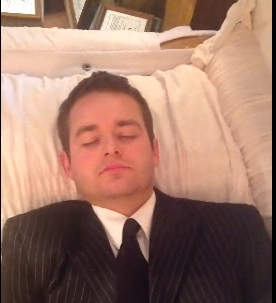

Six. You Could Try “Coffin Therapy”

This is an actual thing that is taking off in parts of Asia. You lay inside a coffin (or casket), contemplate your death and let death wash its life over you. From my readings, most participants find it very enlivening. Although, from personal experience, make sure you choose the deluxe Tempur-Pedic casket if your “coffin therapy” lasts for more than two hours.

Seven. Embrace Your Own Mortality

Mortality isn’t just about death, it’s also about all the things that make us limited, needy, vulnerable, hungry, sexual and human. We have been conditioned by our religious heritage and by societal mores to shame many of the things that come with our mortality. Instead of shaming, embrace.

Eight. Have “The Talk”

It’s not morbid to talk about your death, or ask — say your parents — about their death. This is healthy. It’s healthy to recognize the inevitability that you, and I, will die. And it’s important to express your dying desires through a living will, and how you want your death arrangements to look when it happens.

Nine. DEAD BODIES AREN’T DANGEROUS

If you cared for them in life, care for them in death. Death care isn’t rocket science. Nor do death bodies harbor the plague. If love tells you to care for your dead, do it. Find ways to work with the funeral home, or have a home funeral. The more active you can be in caring for your loved one, I believe the healthier your grief.

Ten. Read books about death positivity.

If you liked the content of this article, (in Billy Mays voice), BUT WAIT. THERE’S MORE. The ideas that you just read are the essential elements that I write about in my new book. If you don’t like the book, I’ll give you a “Two for the Price of One” coupon to our funeral home.

10 Ways the Funeral Industry Has Failed

Don’t worry, I’m going to write a post about the ways the funeral industry has succeeded. But for now, here are ten ways we’ve failed.

One. Disconnected from Community

This is where things start to go horribly wrong. If you don’t have a personal investment in the community, if you don’t love the customers you work for, if you don’t live around them, send your kids to the same schools, shop at the same places, you lose the accountability of love and connection. Once that accountability is lost, death care ethics are on a much more slippery slope. This is why — for the most part — local, privately owned funeral homes are more likely to retain their good name, while large, corporate funeral homes tend to be slightly disconnected and slightly more likely to see this as primarily a business.

Two. Bad at receiving criticism

We’re notoriously bad at receiving criticism. To be fair, nobody is good at it. I mean, who likes to be told that we’re a bunch of racketeers over and over and over again? I know I don’t. Unfortunately, some of that criticism is true! We’re good at listening to market changes, in fact, our funeral director magazines are packed with advice on how we can respond to our customer’s wishes, but when constructive criticism comes from a customer, most of us are too biggety to listen.

Three. Intentionally Kept our Practices Hidden

God forbid we tell you what we do with your loved one. God forbid we publically write about what we do with your loved one. God forbid we blog about it (GASP!!!).

Four. Pushed Embalming Too Hard

Embalming is THE American Way of Death, or at least it was The American Way of Death. Yes, Jessica Mitford popularized that term with her book that holds the same title, but it was funeral directors who coined the term. The term was coined in a response to criticism from religious circles that claimed embalming was a pagan practice (the Egyptians did it for religious, but not Christian reasons). In response, funeral directors said, “No, embalming isn’t pagan, IT’S AMERICAN!” But that America was the America of nearly 80 years ago. America isn’t the same, but funeral directors still want it to be. MAEA! Make America Embalmed Again!

Five. No Support System for Funeral Directors

This is on two levels: funeral directing — like many professions — started as a trade, where the apprentices were trained by masters. Most states (all states?) still require a year of apprenticeship in order to gain licensure, but that apprenticeship needs to continue long after we become licensed. We need mentors to walk us through this trade. Two: we need support groups of some kind that can catch us when we’re falling from the burnout and compassion fatigue that too often comes with this line of work. Currently, most of us have neither.

Six. Too Often Erred on the Side of Business

We should be erring on the side of service. This perspective changes the way we approach money, and it changes the way we approach people.

Seven. Narcissism Checks

We’re called to be directors, to display confidence, knowledge, authority, and strength during people’s weakest moments. But this environment that asks us to lead can too often enable us to self-enhance. We talk over our heads, project authority in situations that are best left to the family and tense up in disdain whenever we’re questioned. There needs to be better checks and balances in place to keep us from sliding towards narcissism.

Eight. Too Much Professionalism

There’s not wrong with being professional. In fact, funeral directors should embody respect, courtesy, and kindness. But, professionalism says something more. It makes a distinction between those who are the professionals and those who are amateurs. Let’s be very clear about one thing: a funeral director’s education, a funeral director’s experience makes them good at helping families with their funerals, but LOVE, and only love, makes someone the best of professionals when dealing with their own deceased. That is, it’s love, and not foremost education and experience, that gives you authority with a dead loved one. In an attempt to embody professionalism, we funeral directors have stolen death care from the true professionals.

Nine. Like Most Industries, WE NEED MORE WOMEN

Amen and amen.

Ten. At times, we’ve failed you

Most of the women and men in the funeral profession are good, smart and service-oriented. But some of us aren’t. And even the good ones can fall into the traps of this business. For that, we’re sorry. We’re sorry if we’ve failed you. We can do better. We will do better.

If you’d like a personal, transparent view of what it’s like to be in the funeral profession, please consider supporting my writing by pre-ordering my book:

On that Decaying Foot that Popped out of the Ground in a New Jersey Cemetery

“I’m so overwhelmed. I’m very stressed, depressed because I’ve never, ever been to a funeral before and seen anything like this.”

The family is considering a lawsuit, and I’m not diminishing the family’s feelings or experience. After reading the article, it does seem like the cemetery could have handled things a little bit better. Although they may not have been able to stop the foot from popping out on Mr. Butler’s casket, they could have been more sensitive in explaining to the family how it happened.

If you’re interested in seeing the dirty of death, and yet the beauty of it, I wrote a book about it:

10 Reasons I’m a Funeral Director

I wrote this blog post four years ago. The photo I used in that post had wee little Jeremiah resting on my chest. Four years later, and Jeremiah occasionally comes to the funeral home “to help dead people”. Times have changed — for one, my hairdresser now trims my eyebrows — but these reasons have remained.

One: Service.

A couple years ago, a granddaughter was giving her grandmother’s eulogy at the funeral home. She shared that before she would take naps at her grandmother’s house, her grandmother would warm a blanket in the dryer, and as the granddaughter laid down, the grandma would drape the warm blanket over her.

After the service was over and before the family closed the lid on the casket, I grabbed the blanket that the family had laid in the casket and warmed the blanket. When I gave the warm blanket to the granddaughter, she couldn’t withhold her tears as now she draped it over her grandmother.

Situations like this arise regularly in the funeral profession. And, as a caregiver by nature, I find great satisfaction in seeing others have more meaningful death experiences because of my efforts. I enjoy serving.

Two: Perspective.

Emerson said, “When it is darkest men see the stars.” We try our best to deny the darkness of death by consciously and unconsciously building our immortality projects. We hope that we can live immortally through such projects.

And then death. Weeping. Our projects come tumbling down. And it’s in those ashes, in the pain, in the grief, through the tears, we see beauty in the darkness. This is a perspective that funeral directors are privy to view on a constant basis. And, in many cases, the darkness can be beautiful.

Three: Affirmation.

Being told, “You’ve made this so much easier for us.” or, “Mom hasn’t looked this beautiful since she first battled cancer”, or “You guys are like family to us” means a lot to me. It’s important to know that what you’re doing is meaningful for the person you’re doing it for.

That verbal affirmation is a big reason why I continue to serve as a funeral director.

Four: Safe Death Confrontation.

When I was a child, I’d lay in bed and imagine myself dying at a young age. I imagined Death as a Monster. That fear, though, has dissipated as I’ve both worked around Death and I’ve grown to be comfortable with my own mortality and the mortality of those I love.

Perhaps there’s no greater freedom than to live life with a healthy relationship with Death. That healthy relationship allows you embracing each moment, realizing that we are not promised tomorrow. This good relationship with Death has been given to me by the funeral profession.

Five: Kisses.

From old(er) women. Big sloppy kisses from older women. And what makes it even better is if they follow up the kiss with a, “If only I was 50 years younger ….”

Six: Power and Obligation. You give us power every time you open up your family life and your grief to us. And when you give us that power, there’s a certain satisfaction that comes with treating that vulnerability with as much honor as we can.

We honor your loved one as we prepare them. We honor you as we serve you. The power you give us, and our obligation to that vulnerability is the grounds that produce honor.

Seven: Lack of the Superficial.

There’s so much BS in the world. We pursue bigger cars, bigger houses and bigger salaries that we become so materialized we can barely stand honesty, vulnerability and spirituality.

That all changes around death. Suddenly, you wish that the time you spent pursing that raise had been spent with your dad. Suddenly, you find some honesty about your life, some perspective and maybe even some spirituality.

I hate BS. I love honesty. I love spirituality. And I love watching as death helps us become human.

Eight: Informs my Perspective on God.

Whether or not funeral directors are religious, you’ll find that almost all are spiritual. Whether or not they believe in God, death has a way of making us look at the deep, the beyond and the transcendent.

For myself, so much of my faith has been informed by the doubt of death. I see God in a whole new dark. And it’s good. In fact, I’ve come to believe that God dwells with the broken because – it would seem – God too is broken.

Nine: Constant Challenge.

Somebody said, “It’s the perfect job for someone with ADHD because there is constant change.” Constant change and constant challenge.

Whether a call at 4 AM; or a particularly tragic death; this job is always pushing us and (hopefully) makes us into stronger people.

Ten: Our Associates.

Today, a nurse – on her own free time – tracked down the hospital release for us. I told her, “You’re wonderful.” Every time we interact with hospice nurses, I always praise them for their work, for their love towards the family. When a church provides a funeral luncheon, I try to tell the workers that they are providing grace in the form of food. When a pastor totally connects with the family, I tell him/her how great a job they’re doing.

When somebody dies – during the hardest moments of life – we see the best in people. As I said in the beginning, sometimes the darkness is beautiful; and, sometimes the darkness makes us beautiful.

There’s many a burden to be borne in this business; which is why I have to remind myself of the reasons I remain a funeral director.

If you’re interested in how I’ve processed death and death care, you can shower yourself death stories by preordering this. If you don’t like it, my mother promises to buy it back.

As a Funeral Director, Here Are 10 Questions You Should Never Be Afraid to Ask Me

One. Can I ask you a weird question?

THERE ARE NO WEIRD QUESTIONS. Dying, death and death care are clouded in a sense of mystery. After our loved ones die, they’re whisked away by the hospital staff, or by a funeral director. Once at the funeral home, the body is either transformed through embalming or cremation. That whole period — from death to disposition — offers all too many questions for the deceased’s loved one. This is why there are no weird questions. Ask us anything and everything and we’ll give you an honest answer.

Two. Can I help?

Firstly, this is YOUR loved one. It’s not ours. One of my sayings I like to tell families to reaffirm that idea is this: “you’ve loved and cared for them up to this point, so don’t stop now.” There are some things we can’t let you help with, like embalming, but there are a hundred other things like dressing your loved one, helping in the transfer, doing the hair, makeup and even riding in the hearse.

URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/timomcd/

Title: Pig’s Heart

Year: 2011

Source: Flickr

Three. Can you fix …?

If you’re having a viewing, it’s always good to pre-view your loved one before the public viewing. If mom’s hair is off, if the clothing isn’t on correctly, if it isn’t your mother lying in the casket … you need to ask us to fix that problem.

Four. Can I see your General Price List?

The General Price List shows the itemized list of our prices so you can make an intelligent financial decision when shopping for a funeral home. In fact, the Federal Trade Commissions requires us to give you this list. The FTC states, “You must give the General Price List to anyone who asks, in person, about funeral goods, funeral services, or the prices of such goods or services.”

Five. Can I have a little longer with my loved one?

OMG, yes. And any funeral director who responds otherwise should be fired. Remember, this is your loved one, not ours.

Six. Can you rub my back?

Embalmers generally massage the arms, legs, and face of the deceased to help with fluid distribution. So, we are able to massage. And even though your body might be strained from grief, we’re probably gonna say “no” to this question. Sorry. You’ve got be dead to get that service.

Seven. Can I watch …?

This is a valid question. Again, most funeral directors will say “no” if you ask to watch an embalming, but just about anything else is on the table. Many crematories will even let you hit the “start” button.

Eight. How can I save money?

Funeral directors should have YOUR best interest in mind, not their own. If you want an inexpensive funeral, the funeral director knows how to cut corners better than anyone. (And, just as free advice, this question should be asked BEFORE your loved one passes. Call around. Ask funeral homes for their GPL. And find one that you’re both comfortable working with, AND, is inexpensive. You could save a couple thousand just by shopping around.)

Nine. “Can you cut out the heart of my husband and have it cremated separately so I can put the heart ashes in a cremation locket? I want the cremation locket of his heart next to my heart.”

This was an actual question a widow asked a buddy funeral director. He said “no.”

Ten. Can you help me with …?

If we got into this work for anything than other than service we’re doing it entirely wrong. It’s not bad if we make money, but the main reason we’ve maintain a place in society is because we’ve helped you in your hardest moments. Good funeral directors are service oriented, and the best ones are both service-oriented and intelligently helpful.

If you like my words, you can buy a whole bunch of them. Please support this project by preordering: