Death

All Souls Day: Giving Our Dead a Place at the Table

Author: jzool

Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/jzool/

Title: she and a ghost

Year: 2008

A couple years ago, my funeral home buried a saint named Jennifer. As far as I know, she didn’t perform any supernatural miracles, like turning water into wine, but she did a kind of miracle that suspends our natural evolutionary tendencies. Per the testimony of her family, she performed her miracles with everyone she met, far surpassing the two-miracle quota required for official canonization.

Jennifer had Down syndrome. Most of the people I know with Down syndrome have a beautifying effect on their family and friends. It’s not necessarily because DS produces more happiness (studies show that depression plagues those with DS), nor is it because caring for someone with DS makes everything easier (although there are reports that divorce rates drop in families that have a DS member), but it seems that position prominence, egotism, and power hunger have little persuasion on these treasured saints of humanity. It’s as if that extra chromosome 21 provides a trade-off, where there’s less mental capability but more character capacity, providing immunity to that desire for survival at other’s expense. And Jennifer had this spades.

Jennifer lived with her parents, Kathy and Don, who were both in their late seventies and retired. On a humid Pennsylvania morning, Don went to wake Jennifer for breakfast and found her lying peacefully in her bed with no apparent signs of a struggle. She was dead.

Jennifer was taken to our county’s morgue where the coroner did her work in trying to determine the cause of death. When a deceased person is a coroner’s case, if the cause of death isn’t entirely apparent, the final cause of death – and the final death certificate – is not issued for a couple weeks while the toxicology tests await their results.

Kathy and Don entrusted my grandfather, my dad and I with Jennifer’s funeral arrangements. Funerals are like a living mosaic. You give away pieces of yourself throughout your life and sometimes many of these pieces come back to form a living piece of artwork … at a funeral. I’ve worked a number of funerals throughout my 15 years at my family’s funeral home, but Jennifer’s display was a masterpiece. This group of people that gathered for Jennifer’s funeral – her living mosaic — created a wonderful aura of kindness, understanding, and togetherness.

In our culture, these living mosaics take place just once in the form of a funeral. And that’s it. But even funerals are becoming less and less engrained in our cultural ethos – for a reason I can’t entirely put my finger on – we’re slowly moving the dead out of the spaces of the living. Maybe we think it’s morbid to give the dead space? Maybe we’d just rather forget … or we think remembering is too painful? Maybe we think this ostracization is a part of closure?

When we do remember, it’s often something that we stumble upon, passively, and hardly ever corporately. We smell our dad’s cologne in a crowded street and we’re suddenly brought to tears. We find a picture of our grandmother stuffed in our desk and our mind is flooded with memories. As beautiful and cathartic as these passive experiences can be, I’d like to think that it would be even healthier if we invited our dead into our spaces through a more active form of remembering like Kathy and Don did with Jennifer when they gave her a communal space even after her death.

A couple weeks after Jennifer’s funeral, the final death certificates arrived at our funeral home with “sudden cardiac arrest due to sleep apnea” inscribed as Jennifer’s cause of death, a cause that was expected now finalized. I called Kathy and let her know I’d be willing to bring the death certificates to her house, she agreed and an hour later she and her husband welcomed me into their home to show me something they made for Jennifer. I write about what I saw in my book:

“Come into the kitchen, she said. I walked through the archway into the kitchen and saw something I’d never seen before. Jennifer’s place at the kitchen table was covered with a shrine – a collection of items that had been meaningful to Jennifer. I had associated a shrine with the worship of a demigod or saint, but Jennifer’s family took the broader meaning. They dedicated this spot entirely to the memory of their daughter.

“We thought it’d be a good idea,” Kathy said. I was slightly taken aback by the whole thing. If you had asked me the first word that came to mind when I saw it, I would have said ‘weird’, maybe even ‘pathological’. But after Kathy started to explain the different parts of the shrine and their meaning, I understood my reaction had been hasty.

Looking back, I see that my initial problem with Jennifer’s shrine was that it didn’t portray that strong American sense of tackling and overcoming grief. Americans love to problem-solve, and we hate sitting in the tension, and many of us, even some therapists, see grief as a problem that needs solving, a wound that needs healing, and a chapter that needs closure. But Jennifer’s shrine stood in the tension of avoidance and closure and acknowledged that grief is present, it’s present in this home, and that’s okay.

Somewhat unknowingly, Kathy and Don were practicing All Souls Day, the day some believers actively give their dead space among the living. Days like All Saints and All Souls are more deeply felt in other cultures that know how to exist in the tension of the presence of our dead, but for many of us, it’s a nearly forgotten day that comes after the costumes and candy of Halloween.

The term “saint” has a lot of baggage attached to its meaning, and maybe that’s where we lose our way. We’ve packed it with religious meaning and holiness and miracles. But it’s a term that we need to reclaim if we’re to venerate the lives of our elders, and find their power and love in the present. If we remove the baggage and strip it down to its core, we’ll find we all have had saints in our lives, saints who have molded us for good. Maybe it’s your mother who tirelessly encouraged you to pursue your dreams. Maybe it’s your grandfather who stepped in when you Dad left home and family. Maybe it’s the family matriarch who guided your family with her prayers and grace.

These dead – our saints – need to have a space at our table, sometimes literally like Kathy and Don’s shrine, sometimes figuratively. By connecting to our dead, by actively remembering our saints, by swinging back into the past, we can be more settled in our present and propelled into our future, connecting the circle that is so often broken by when the dead are excluded. This is about making us whole by accepting that things gone are still present. It’s about self-realization as an individual and as a family by letting our history inform our inner person. It’s about giving voice to a people that although dead are still speaking. It’s about actively remembering by making sure that our saints, like Jennifer to Kathy and Don, still hold space in our lives.

During this season of Allhallowtide, I’ll leave these thoughts with this question: What are some ways you and your family can practice active remembering and bring your saints into your present?

My book is now available for purchase (click the image to see the Amazon page):

Seven Characteristics of the Broken Open Heart

Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/sweethaa/ Title: A Broken Heart Year: 2009

I write in my book,

When hardship comes, some hearts are broken apart, and like pottery or glass, those hearts are difficult to put back together. But other hearts are broken open like a fist that opens itself to receive and give back, or like clay that adapts to pressure. Whereas death’s wildeness can shatter the well-ordered, rigid life, it can open those who have learned to flow with the waves of life. The broken-open heart, the heart that has been molded by pain and suffering, knows to “be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about.”

One. One of the factors that differentiate the broken open heart from the heart that’s broken apart is this: the broken-open heart doesn’t believe that brokenness is shameful. The broken open heart starts with the assumption that it’s okay to be broken. It’s okay to feel deeply. It’s okay to have your life washed over by the emotions of death. On the flip side, sometimes we respond to our brokenness from a place of shame and fear. We fear our emotions. We fear grief. We fear being sad. We fear death itself and we absolutely fear the perceived imperfections of such brokenness. “Because anything that’s broken isn’t perfect and isn’t lovable,” we think.

Two. The broken open heart doesn’t see emotional turmoil as an unlovable imperfection. The idea that broken things can’t be loved is simply untrue, but the ever pervasive narrative that’s perpetuated through Hollywood and everywhere else is that only perfect things can be loved. Somewhere deep inside the broken-open heart resides a belief, however small, that says, “perfect things are broken and we can be loved.”

Three. Befriending death and all the brokenness, fear, and perceived imperfection that comes with it often gives us room for others’ pain. By accepting our own pain and stripping it of shame, we’re able to accept the pain of others. By accepting our own perceived imperfections, we can more easily accept the perceived imperfections in others.

Four. “It uses its own pain to find love for those we don’t like.” Simply put, the broken open heart has room for other broken things. Everyone can see the broken imperfections of others, but the broken open heart looks past the imperfection others and does the courageous work of seeing the pain behind the brokenness.

Five. “The broken-open heart seeks to understand.” When we are able to befriend our own brokenness, we start to see the deep connection between pain and real-world actions, and attitudes. In fact, many of the people we don’t like, people who are different than us, or people who think differently than we do aren’t inherently different than we are, they are just responding differently to the pain in their lives. If we can understand a person’s pain, we can begin to understand the engine of their being.

Six. The broken open heart is “slow to take offense and quick to forgive” because when we understand the pain behind the actions when we allow ourselves to lean into the pain, we can see that their offense is more a response to their pain than to us. Yes, pure evil exists in the world, but even those that are evil are responding to evil done to them. Sometimes people are just mean, but most of the time they’re just projecting their pain onto us.

Seven. “The broken-open heart uses grace to build and bind the broken.” When we find a path through our brokenness, we learn a very hard-earned lesson: finding wholeness doesn’t come through shame, it doesn’t come through criticism, it doesn’t come through fear of punishment (or fear in general). Our path through brokenness is made possible by love and grace.

Most of us guard our heart and for good reason. We’ve been hurt by the ones we have loved, by those we’ve trusted and those who we’ve given an intimate piece of our souls. But somewhere in the midst of all that heart protection, there’s a little opening that still harbors a sense of trust, courage, and love. As I deal with my own brokenness, and as you deal with yours, I hope you find ways to fan the embers buried deep within your heart. I hope that we can all find a way to be broken open.

If you want to read more about my broken-open journey with death care, here’s the book I wrote.

“Welcome, Sister Death!”

“Keeping Away Death” on The Fulton County Department of Health and Wellness

My first couple years in the funeral business nearly destroyed me. Growing up as the son of a funeral directing family, I had danced around death for most of my youth. When I finally danced with it upon full-time employment at my family’s funeral home, all I could see was darkness. I had a death negative narrative, a pair of lenses that viewed death as devoid of goodness and full of fear. I suppose most of us do.

In my book, I list five reasons this narrative is so strong; such as the professionalization of death care, the religious belief that death is a punishment for sin, and our evolutionary heritage. This narrative doesn’t exist in every culture, but it’s so strong for us in Western culture even death’s personification is this scary and dark figure we call the “Grim Reaper.”

The rise of the cold and bony Grim Reaper began during the 14th century, as the Black Death swept over Europe leaving anywhere from 25% to 60% of Europe’s population dead. Those infected suffered high fevers, seizers and possible gangrene of the extremities. Such an awful death produced a fear among the healthy, who regularly abandon their affected spouses and children. Not surprisingly, Death was depicted as the Grim Reaper, a bony figure with no flesh and no feeling with a scythe that mows down the living with reckless abandon. What is surprising is that this personification of Death didn’t die out with the Black Death, but remains THE depiction of death in Western culture today.

After my closeness with death nearly destroyed my own life, I knew that I’d either have to find something more in death, or I’d leave the business. As I searched, I began to see that death wasn’t entirely bad … it was deeply human. I write in my book, “I tremble to say there’s good in death, because I’ve looked in the eyes of the grieving mother and I’ve seen the heartbreak of the stricken widow, but I’ve also seen something more in death, something good. Death’s hands aren’t all cold and bony.”

Death isn’t the Grim Reaper. It isn’t unfeeling. It isn’t subhuman.

Marzanna is death personified in Baltic and Slavic lore. Unlike the “Grim Reaper” with the bony hands, or other popular personifications of death, Marzanna takes on the gender of a woman, as she’s not only associated with death but the rebirth of death in nature. Neil Gaiman brought a Marzanna type depiction to his comic book series, The Sandman. Gaiman’s Death is a beautiful, youth goth woman who is kind, relatable and nurturing. She’s nearly the exact opposite of the Reaper, a welcome sight to be sure, and one that continues to be a fan favorite.

As much as I like Gaiman’s personification, there’s another personification of death that comes from St. Francis of Assisi (1181/1182 – 3 October 1226) that is more intimate still than Gaiman’s Death.

St. Francis committed his life to serving the poor, a commitment that inspired a following in the Catholic Church known as Franciscans, and a Pope who took Francis as his papal name. St. Francis of Assisi is also the patron saint of animals and nature, a facet of his life that is surrounded by folklore stories that tell of him preaching to birds and taming wolves. Folklore aside, St. Francis’ “Canticle of Brother Sun and Sister Moon” speaks of his intimacy with nature and love for it. In the Canticle, Francis goes through many of the natural occurrences — moon, sun, wind, water, fire, earth — framing each part as his sister or brother. To end the Canticle, Francis takes a surprising turn and thanks God for “Sister Death.”

As someone who felt deeply connected to nature, we shouldn’t be surprised that Francis saw Death as something intimate, something natural. Francis believed that all nature was good, although some of it needed redemption. It’s said that when Francis was dying, he told death to praise God, which was his way of calling death to not be painful or harrowing, but good. He believed death to be such an ingrained part of the natural order that it too — like all of nature — harbored a sense of goodness, even though it can often be cruel and terrifying. Like the fable of St. Francis and the wolf, he saw past the cruel and hoped for the good. According to the Transitus, at his life’s end, Francis proclaimed, “Welcome, Sister Death!”

Assisi’s “sister death” is a visage of death that asks us to see death as intimate, as something we’re deeply related to. It’s not some scary, distant creature of evil like the Grim Reaper, although neither is it a happy, painless experience. It isn’t something other than us, it’s a part of us. Death is ours. If we’re looking for the face of Death in a narrative that isn’t death negative, it’s St. Francis’ Sister Death, a face that closely resembles our own.

This reframing helps us interpret life’s end as something not cold and distant, but something that is entirely human. Death, after all, is ours. And I do believe if I had entered my dance with death with a different image, a different personification of Death, my view of it wouldn’t have been so disheartening. How we view death influences how we experience it. It’s time for a new visage, and maybe St. Assisi’s figure can help.

This is the first in a series of articles dealing with the “10 Confessions” of my book. If you’d like to order the book, click on the image below:

101 Things I’ve Done as a Funeral Director

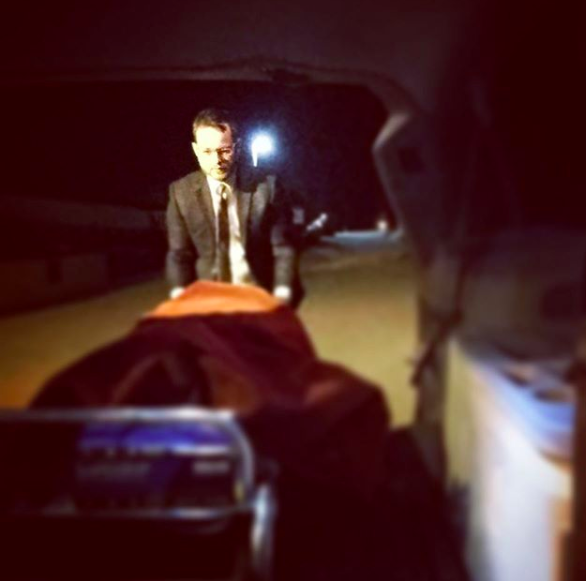

Note: there’s no body on the stretcher.

When you’re a funeral director, your primary concern is people: both the dead kind and the living. And when you serve people, you do some weird things to meet that end. Death is all wrapped up in life, in the mundane, the messy, the maddening parts of living. Since, death is wrapped in life, it’d only make sense that those of us in death care do a bunch of things. Here are 101 things I’ve done.

- Helped change a random baby’s diaper at a viewing.

- Removed a dead person’s adult diaper.

- Warmed up a bottle of baby formula.

- Wiped a deceased’s person’s ass.

- Cleaned the funeral home’s toilets

- Cleaned the morgue floor.

- Cleaned the blood of the deceased off of his bathroom floor.

- Shoveled snow at the funeral home

- Shoveled a path through the snow back to the deceased’s trailer.

- Gave the deceased’s German Shepherd some water while it sat in the visitation line at the funeral home.

- Comforted a dog as we carted his friend/owner out of the house.

- Comforted a family with some coffee from Dunkin Donuts.

- Made a McDonald’s run for a family during a funeral.

- Parked cars in a funeral procession line.

- Fixed a car’s door while it sat in a procession line.

- Washed a car in the procession line.

- Washed the hearse a thousand times.

- Washed vomit out the back of the removal van.

- Washed blood out the back of the removal van.

- Carried a dead person down multiple flights of steps.

- Carried a dead person up from a basement.

- Carried a dead body in rigor mortis fireman-style off of a toilet.

- Embalmed old people

- Embalmed young people.

- Embalmed my grandfather.

- Embalmed a motorcycle accident victim.

- A burn victim.

- Suicides of all varieties.

- A person run over by a train.

- Drove the deceased’s family to a train station.

- Drove the deceased’s family to the airport.

- Chauffeured the deceased’s family to a cemetery.

- Chauffeured the deceased’s family to a bar.

- Pushed people in wheelchairs into the funeral home, through cemeteries, and out of the way at nursing homes.

- Helped carry crying people’s purses.

- Helped carry crying people’s water.

- Helped carry crying people.

- Once used smelling salts on someone who fainted at a graveside (wouldn’t do that again).

- Once fall into a grave.

- Once helped someone out of a grave.

- Helped lower numerous caskets into graves.

- Helped clean up the tent and lowering devices at the grave.

- Got cemetery dirt on my suit.

- Got blood on my suit.

- Got vomit from a dead body on my suit.

- Got vomit from a baby I was holding at a viewing on my suit.

- Ripped my suit so far that my underwear was showing.

- Sweated in my suit.

- Nearly froze in my suit.

- Dressed many a man in their suits.

- Dressed many a woman in their burial clothing.

- Put a teddy bear in the casket with the deceased.

- Helped kids put cards in the deceased’s casket

- Watched people put whiskey in a deceased’s casket.

- Watched people put a dime bag of pot in a deceased’s casket.

- Watched people jump into a deceased’s casket.

- Helped pull them out of the deceased’s casket.

- I’ve closed the lid of a casket.

- I’ve closed the mouth of many a deceased.

- I’ve closed the eyes of the deceased.

- I’ve closed autopsy Y incisions.

- Embalmed autopsied bodies.

- Seen all the insides of an autopsied body.

- I’ve held a brain.

- Held a heart.

- I’ve held the hand of a grieving mother.

- Listened to the cries of a grieving mother.

- Listened to the laughter of children at funerals.

- Performed magic tricks for children at viewings.

- Played hide-and-go seek with children at viewings.

- Played hide-and-go seek as a kid in the casket showroom

- Worked night viewings.

- Gone on death calls in the middle of the night.

- Gone on death calls in the middle of a snow storm.

- Used my Subaru Forester for a death call during a snow storm (the stretcher just fits).

- Used an old Land Rover for a death call during a snow storm.

- Negotiated with Insurance companies on behalf of families.

- Negotiated with doctors on behalf of families.

- Negotiated between family factions during funeral arrangements.

- Stopped fights at funerals.

- Played bouncer at funerals when families don’t want a certain person to attend.

- Removed people from funerals.

- Removed catheters.

- Removed pacemakers.

- Forgot to remove pacemakers that consequently exploded in the crematory.

- Taken pictures of tattoos before the person was cremated.

- Made picture slideshows for families.

- Restored and photoshopped photos for obituary notices.

- Wrote thousands of obituaries.

- Filled in as a makeshift altar boy.

- Helped fold a flag at a graveside service.

- Said a prayer at a graveside service when the pastor didn’t show.

- I’ve been the soundman at churches.

- Been the DJ at viewings.

- Helped men at viewings tie their ties.

- Joked about tying dead people’s shoe strings.

- Joked with families to help relieve the tension.

- Hugged thousands of people to help relieve the tension.

- Listened to people to help relieve their grief.

- Allowed death to shape my story.

- Wrote a book about it all.

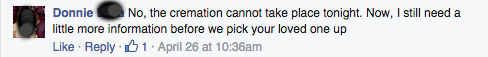

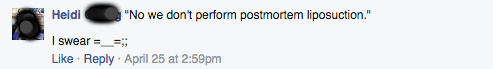

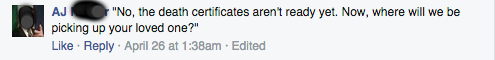

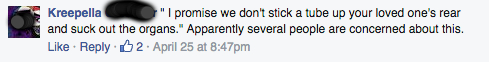

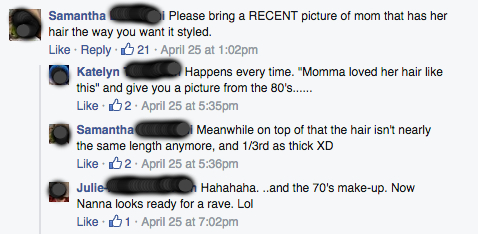

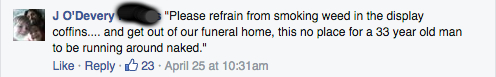

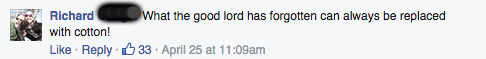

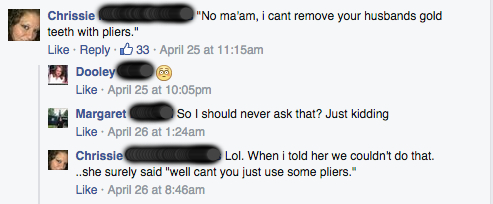

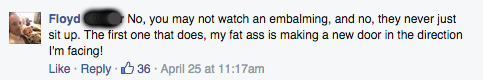

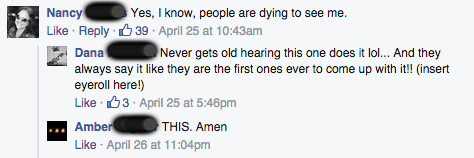

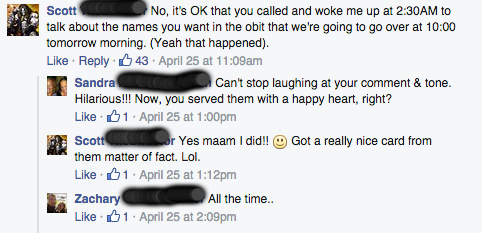

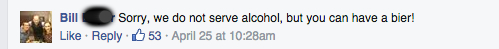

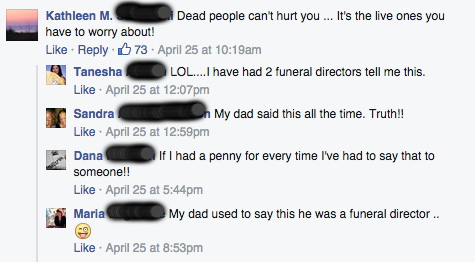

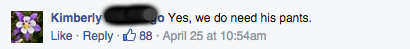

20 Things Funeral Directors Say

This post is collected from the Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook community:

One. Two.

Two. Three.

Three. Four.

Four. Five.

Five. Six.

Six. Seven.

Seven. Eight.

Eight. Nine.

Nine. Ten

Ten

Eleven.

Eleven. Twelve.

Twelve. Thirteen.

Thirteen. Fourteen

Fourteen Fifteen.

Fifteen. Sixteen.

Sixteen. Seventeen.

Seventeen. Eighteen.

Eighteen. Nineteen.

Nineteen. Twenty.

Twenty.

If you’re interested in the life of a funeral director, here’s my story, told with humor, spirituality, and transparency.