Death

“This Funeral Isn’t About You”

That’s what I wanted to say.

If you know me, you know that I tend to be blunt. Awkwardly so.

Being that blunt objects aren’t allowed at funerals, I’ve had to learn the art of professional speak. Professional speak in the funeral business is the art of saying what you want to say without really saying it.

Situation Number 1:

Blunt Caleb: “When we picked your dad up from the nursing home, he was looking all purple and reddish, but after we embalmed him, we were able to flush the discoloration out of his face.”

Professional speak, “Your dad looks great.”

Situation Number 2:

Blunt Caleb: “Do you want that beard shaved off your mom’s face?”

Professional speak Caleb ignores asking that question all together and just shaves mom’s face.

Americans — maybe even Westerns as a whole — are impatient. We rarely have quiet. The TV’s constantly on. Our smart phones are ever at our side. Ear buds in our ears. Meditation is a foreign concept. Prayer is avoidable at all costs. And the patience learned in the silence is never attained. And then comes death and the silence that comes with it. The meditation. The prayer. The lack of words. And when the results of grief work don’t come immediately, we become impatient and think, “Something is dreadfully wrong with me!” And we’re right. We usually conclude that we’re deeply depressed; the reality may simply be that we’re deeply and intrinsically impatient, unable to find the peace in the silence that comes from death. Maybe we’re just as afraid of the silence as we are of death.

Death brings its own pace of life … its own schedule. It’s never convenient. But we want it to be. We want to control it. We want to put it on an itinerary that fits our fast paced, purpose driven lifestyles.

Perhaps that battle for control is nowhere more apparent than at a viewing, especially when the viewing line mimics the slow moving, long lines we see at a popular amusement park ride.

This past Saturday night, I stood there behind the register book, striking up conversation with people as they enter the sanctuary. The viewing line snakes around the church, down the hall and into the basement as we try to extend it through the corridors of the church so as to keep the line from going out into the cold elements of a Pennsylvania winter. The family of the deceased is taking their time, talking to each and every person who has come out on this chilly night.

“Other funeral directors stand by the family’s receiving line and tell them to keep their conversations short and simply”, one person stated.

“We don’t do that”, I said politely.

Another couple comes through the line and complains that they’ve been standing in line for half-an-hour AND by the look of things, they’ll probably be in line for another half-an-hour. “Can’t you do anything?” they beg.

I try to make a joke … I tell them that, like Disney World, we are going to create an express line, where you can bypass the crowd for a fee. “That’s a great idea”, they say. “We’d pay $50 to skip this line.”

After having this conversation about 10 times over the next hour, I’m getting tired of my joke and I’m getting tired of people complaining.

I want to pull them close to my face and whisper, “This isn’t about you.” But that would be blunt Caleb speaking and that Caleb isn’t allowed around death.

Perhaps the greatest loss that comes with the drone of our busy lives is that in losing silence, we’ve lost patience, and in losing patience we’ve become so inherently selfish that when we go to a funeral we forget that it’s not about us.

Battling Burnout: How Funeral Directors Find Peace in the Midst Of Chaos

(This article was originally published in the October issue of The Director. Written for ASD – Answering Service for Directors by Jessica Fowler. Used by permission.

We — at the Wilde Funeral Home — daily use the answering services of ASD; and our customers, no matter how distraught when they call, are always met with a professional and caring voice.)

Funeral Director Thomas Gale counts ceiling tiles. Each one represents another moment in his life to remember not to take for granted. For nearly 20 years, Gale has been a funeral director at Currie Funeral Home in Kilmarnock, VA, and has learned how to balance his professional and personal life after his own brush with mortality.

Gale remembers lying immobile in a hospital bed during a heart procedure several years ago, his only outlet the ceiling tiles above him. When he counts them now, it is to remind him to take regular breaks, set time aside for hobbies and accept assistance from others.

“We take better care of our cars than we take care of ourselves,” Gale says. “If you see a blinking red light in your car, you’re going to pull off the road to get it serviced. Yet, we have warning signs go off in our lives all the time, but we keep driving until we have a major crash.”

A funeral home operates on a constant, 24-hour rotation that never sleeps. On a daily basis, funeral directors must deal with economic, operational and emotional stress, as well as the demands of providing compassion to the bereaved. In Funeral Home Customer Service A-Z: Creating Exceptional Experiences for Today’s Families, author Dr. Alan Wolfelt outlines the symptoms of what he calls “funeral director fatigue syndrome.” Known generally as “compassion fatigue”, this syndrome is common among caregivers who focus solely on others without practicing self-care, leading to destructive behaviors. Some common symptoms include:

*Exhaustion and loss of energy

*Irritability and impatience

*Cynicism and detachment

*Physical complaints and depression

*Isolation from others

While the admirable goal of helping bereaved families may alone seem to justify emotional sacrifices, ultimately we are not helping others effectively when we ignore what we are experiencing within ourselves,” Wolfelt says. “Emotional overload, circumstances surrounding death and caring about the bereaved will unavoidably result in times of funeral director fatigue syndrome.”

Dramatically changing these behavior patterns and adopting positive, healthy habits help these symptoms diminish overtime. While it can be easy for funeral directors to get swept up in the workload, it is often considerably more difficult to allocate free time for leisure. Here are some tips from directors and experts on how to defeat feelings of funeral director burnout:

Family Matters

According to Tim O’Brien, author of A Season for Healing – A Reason for Hope: The Grief & Mourning Guide and Journal, funeral professionals must maintain a near-constant demeanor of strength and self-possession, rarely displaying their emotions.

“Those characteristics are exactly why they need to take time for themselves and practice sound stress management techniques,” O’Brien says. “Yes, they do have to show outward composure and be the steady hand in public. However, they can and should have private time for exploring and expressing emotions. The alternative is often premature death.”

In a recent article for The Director, O’Brien cited irregular hours, interpersonal relationships with employees, limited free time and the often-depressing environment that grief can create as some of the main reasons directors experience compassion fatigue. However, finding a way to strike a balance between professional and personal isn’t as simple for small town funeral homes where the two categories are often one and the same.

Director Stephen Hall grew up in the funeral home business and has worked at the family owned and operated Trefz & Bowser Funeral Home in Hummelstown, PA since he was 12 years old. As an experienced director living in a small town, it is often difficult for Hall to step away from his numerous responsibilities but he has found that the nature of the job offers its own share of rewards as well.

“When my kids were younger, if there was a slow day at the funeral home I was free to attend activities at school because I set my own schedule,” Hall says.

The fine line between personal and professional has always been especially faint for Funeral Director Derek Krentz. He resides at the Gardner Funeral Home in White Salmon, WA with his wife Dominique, also a director, and their children. While Krentz rarely takes vacations, he feels fortunate to work side by side with his wife and still function as a family.

“Its not on common for the kids to do their homework while we’re working. Very often we’re folding memorial folders and laundry at the same time in the middle of the living room floor,” Krentz says. “We rarely go anywhere more than an hour away. You just learn to enjoy being at home.”

Embrace Technological Solutions

In the past, funeral professionals would remain near their firm’s telephone at all times to secure new business and provide families with assistance day or night. Many firms still operate with skeletal staffs, employing only a handful of full-time employees to share the workload. However, in the past decade, new technology and services have emerged that cater to the funeral home industry and help directors conduct business more efficiently.

“With new technology, we’re no longer tethered to a physical location anymore,” Hall says. “Pagers and cell phones have given us the freedom to run our business practically from anywhere.”

Improvements in telecommunications have allowed directors to remain available to families anytime they step out of the office. Whenever Hall has to step out of the office, either for a few minutes or for the evening, he forwards his phone lines to a funeral home exclusive answering service that records detailed messages and contacts Hall for any urgent or first calls.

“When ASD (Answering Service for Directors) came around it was a god send because their people know the profession. All of our calls are screened so we only have to address important concerns right away. ASD can field a lot of the questions that would have been another phone call for me to make,” Hall says. “Now that they have broadened out with the web connection I can log in to see the activity and if there is anything that needs to be addressed immediately.”

Other organizations work to decrease the time consumed by daily tasks at the funeral home. Life insurance assignment companies expedite insurance payments that can otherwise take months for funeral homes to receive. Many funeral professionals rely on removal services to transport decedents after office hours. Software companies have adopted new technology to speed up the process of death certificate filing, obituary placement, and much more.

Yet there is a still a slight stigma associated with modern funeral home practices and some multi-generational and small town firms continue to employ an older business model based on 24/7 availability. Many funeral home owners avoid hiring extra help or seeking assistance from other companies in an effort to provide families with a more personal touch.

“I’m not that computer savvy so I just prefer sitting down with a family while they’re making arrangements and write it down rather than type it into a computer,” Krentz says. “I just find it more personable.”

As President of the Association of Independent Funeral Homes of Virginia and a director in a small, tight-knit community, Gale knows first hand the pressure placed on directors to uphold traditional values. It is the reason why he still sometimes counts the ceiling tiles above his desk—to remember to never ignore his own needs or take his life for granted.

“I remember the old regime of remaining available all the time,” Gale says. “While you still have to be available, you don’t have to do it all alone.”

Care For Yourself So You Can Care For Others

According to O’Brien, funeral professionals are highly likely to develop compassion fatigue without “professional detachment, a positive attitude in the midst of an apparent negative atmosphere, regular personal time and good dietary, sleep and exercise habits.”

Every person needs an outlet: an activity they enjoy that should never feel like work. For funeral professionals, it is essential to seize any opportunity for personal enjoyment, even if only for a few hours.

“I don’t get away a lot but I’ve learned that when things are slow, go fishing, because you don’t know when the phone is going to ring again,” Krentz says.

Like Kretz, Gale is also an avid fisherman and finds the peace and serenity of being out on the water help him restore his state of mind and return to the funeral home with a clearer perspective. He also believes that surrounding yourself with other community members is invaluable to never losing sight of the reason you do your work.

According to Gale, “You’ll become a better person, a better funeral director and just a better over all servant to the people around you if you can care for yourself.”

A change of scenery is also a vital ingredient for maintaining a balanced lifestyle. Apart from the time spent away, physical space acts as a barrier between the mind and the stress agent, in this case, the funeral home office. No one can consistently give 100 percent day in and day out. Regular breaks provide the rest necessary to renew motivation for returning to work.

Last year, Gale took a vacation to spend time with his family in Virginia Beach, VA. For the first time ever, he wanted to free his mind and pretend for one straight week that the funeral home did not exist. At first, the time apart was excruciating. He spent the first 24 hours fighting the urge to check his messages, unable to break decade-old habits of remaining on top of all business, no matter the time or day.

Eventually, he was able to settle in and truly enjoy his break.

“Even the greatest of engines can’t run all of the time without being serviced,” Gale says.

*****

Jessica Fowler is a freelance writer and Public Relations Specialist for ASD – Answering Service for Director where she has answered calls for funeral homes for more than 8 years. Jessica earned her Degree in Journalism from Temple University in Philadelphia, PA and has written articles for The Director, Mortuary Management and American Funeral Director in addition to local travel publications. She can be reached at jess.fowler@myasd.com.

Jessica Fowler is a freelance writer and Public Relations Specialist for ASD – Answering Service for Director where she has answered calls for funeral homes for more than 8 years. Jessica earned her Degree in Journalism from Temple University in Philadelphia, PA and has written articles for The Director, Mortuary Management and American Funeral Director in addition to local travel publications. She can be reached at jess.fowler@myasd.com.

Talking to Your Children about Death

This from “Death and Dying, Life and Living” (Page 346):

In our society, adults often wonder if they should talk to children about death, what they should say, and how they should act with children in death-related situations. These questions arise in many ways:

Should we discuss death with children or teach them about loss and grief even before a death takes place?

What should we say to children after a death occurs?

Should we take children to funeral services?

Perhaps the most difficult of all questions of this type arise in situations in which adults (parents, family members, or care providers) are challenged by a child who has a life-threatening illnes and who is facing his or her imminent death.

One recent contribution to the discussions (Kreicbergs et al., 2004) described a study of Swedish parents whose child had died from cancer between 1992 and 1997. Among the 561 eligible parents, 429 reported on whether they had talked about death with their child. Results showed that more than a quarter of those who did not talk with their child about death regretted that they had not done so. Similar regrets were reported by early half of the parents who had sensed that their child was aware of his or her imminent death. By contrast, among the parents who had talked with their children about death, “No parent in this cohort later regretted having talked with his or her child about death (p. 1175).

The implications of this study suggest that, despite all of the challenges involved in talking to a child about death and even in the very demanding circumstances of a child facing his or her imminent death, it is most often better to go ahead with such conversations. The main reason for this is that, as Rabbi Earl Grollman has often said, “Anything that is mentionable is manageable.” Opening a line of communication with children is preferable to allowing them to try to cope on their own with incomplete or improperly understood information and the demons of their own imaginations. In addition, a child who is able to have his or her concerns addressed in a thoughtful and loving way is a child who has someone he or she can trust when there is a need to look for a source of support.

I Don’t Smile When I Embalm Bodies

Earlier this week a contentious discussion brewed on my Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook page. And I’d like to address the topic in my blog’s forum.

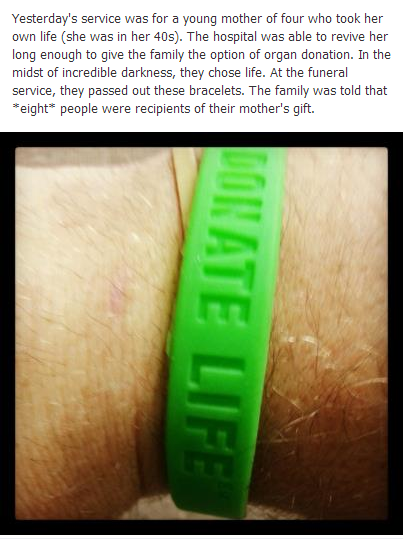

The discussion was kick-started when I posted this status:

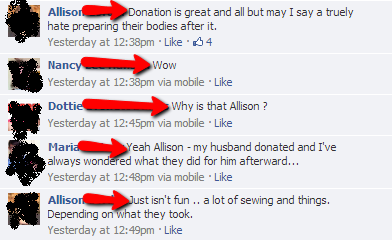

The second comment on the above status was from a fellow embalmer named Allison, who said this:

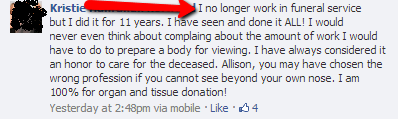

Allison’s initial comment eventual prompted this comment from a former embalmer named Kristie.

First off, let me say it’s possible for an embalmer to be both 100% for tissue/organ donation and not enjoy the process of preparing a donor. It’s possible for us to be both professionals and human. I’m one such funeral director. I am firmly and unequivocally a supporter of those who choose to find life in a tragic death, and yet when a donor body comes through the morgue door, it’s not Christmas morning.

I know that the best donors are usually young and they usually die from tragic (not necessarily violent) circumstances that leave their body in decent condition to be harvested.

I have immense respect for families who — in the midst of incredible tragedy and darkness — find a way to overcome their pain and chose life by allowing for the harvesting of a body they love so dearly. This act of donation is one of the few genuinely unselfish acts to be found in humanity.

Yet, while I recognize the intense moral beauty and life saving value of organ donation, I’m less than excited to embalm and prepare a donor’s bodies.

Each funeral home and funeral director is different. Some funeral homes are large enough to have shift work; still others are large enough to employ full-time embalmers, who basically embalm body after body all day. Some funeral homes have secretaries, prearrangement directors, at-need directors, full-time pick-up people, etc., etc. But for many of us small firms, we play role of embalmer, secretary, pick-up/livery person, funeral director, at-need director and pre-need director. We’re on call 24/7 and rarely have an uninterrupted holiday.

Our personal lives are not just blurred with our professional lives, they become one and the same, often resulting in sad endings. Divorce. Depression. Burnout.

Our pay doesn’t always justify what this profession takes from us. According to the BLS, the average embalmer makes $45,060, which isn’t bad until you consider that the salary often comes at the expense of our souls. I’ve worked 20 hour days. I’ve worked 100 hour weeks. Most months I get two days off. This month, my weekend off happens to be this weekend and with the snow coming, I may have to work the plow on one of my “days off.” And when I am home, it’s hard to get comfortable as I’m one phone call away from going back to work.

I was up until 12 midnight writing this post and then at 3:30 AM I was called into work. I won’t be finished work until roughly 5:30 PM.

Here’s a picture of me at the nursing home at 4:40 this morning. The smile is real … the nurses were making fun of me for taking the photo.

And although this isn’t about me and the burdens I carry, I will say that my experience isn’t exceptional. The at-need demand, emotional and long hours take their toll on us as people.

So, when the heart is donated and I have to raise six arteries instead of one, I don’t smile.

When there’s bone donation, I don’t look forward to moving the Styrofoam rods around to make the appendages look natural.

When skin is grafted, I don’t smile when I’m cleaning the seepage off the floor.

When I get various liquids on myself because of the intrinsic messy nature of donor bodies, my face doesn’t crack a grin.

Unless I’m listening to stand-up comedy on the morgue’s radio, I don’t embalm bodies with a smile.

I appreciate Kristie’s assertion that she has never thought about complaining when preparing a body. And I appreciate that she always sees it as an honor. I will be the first to admit that Kristie is probably a better person and funeral director than I am. Maybe her suggestion to Allison (that Allison should find another profession) applies to me as well.

But, I, in contrast to Kristie, think it does us funeral directors well to be honest. Maybe not in a public forum like I’m doing now, but we need to recognize that we’re both professionals and human. We love to serve you, but there’s times when we too need to be helped. We need to fight that perception that to be a professional means being an unfeeling robot. We need to ask for help, sometimes we need to seek counselling. If you’re a funeral director and you don’t embalm donor bodies with a smile, it’s okay.