Death

Ten Tips to Help Children Grieve

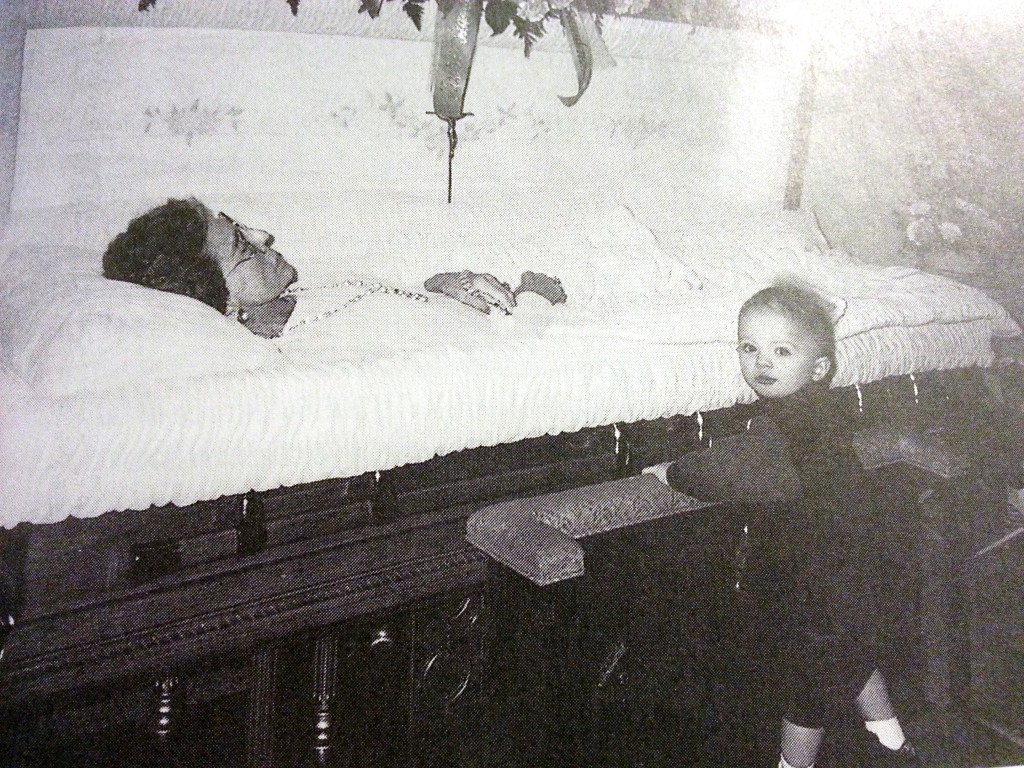

In the Western world, death is one of the last taboos. Death has become so sterile … so unspeakable … so frightful … so improper … that we assume we MUST protect the innocent souls from it’s darkness. In many parental minds, those “innocent souls” who need the most protection are our children. So we shield them from death, and keep them away from funerals, viewings and the dead.

Death, though, isn’t something that we CAN protect our children from. As much as we want to give our children security and answers to their questions, death, by it’s very nature, takes away security and only provides questions. The desire to protect our children from death is understandable, but it is a part of life that — if ignored — only becomes more difficult, more frightening and more harmful. It’s a part of life that may provide some of the best teaching moments for your children. Teaching moments where you can share that:

Life has an end.

Love continues on.

We have to live and love as much as we can because we don’t know how long we have.

All of us will die, so we must pursue our dreams and enjoy the life we’ve been given.

Not only should we recognize that death confrontation provides our children with incredible teaching moments, we should also realize that children do indeed grieve. They are connected. They love. They feel. And so when death comes, they grieve. Depending on their developmental stage, they will grieve differently than adults. But as long as they are apart of our family, of the community of the deceased, they have the right to grieve with us.

Here are a few helpful tips that I’ve gathered from three separate Counseling journals about how to help your children grieve:

- When death happens, have a close relative, preferable a parent, tell the child about it immediately.

- Stay close to the child, giving them physical affection. Instead of pushing them farther away from the community during death, draw them closer into it.

- Children grieve in cycles. For example, they may be more inclined to play and divert their focus from the death when the death is recent and parents are grieving intensely. More than adults, children need time to take a break from grief. It is important to know that it’s okay to take a break. Having fun or laughing is not disrespectful to the person who died; this is a vital part of grieving, too.

- Avoid euphemisms such as, “passed on,” “gone away,” “departed”. In and of itself, the concept of death is difficult enough for a child to understand; using euphemisms will only add to the difficulty.

- Advise the child to attend the funeral, but do not force him or her to go. The funeral and viewing is the community expression of grief. As a part of the community, it’s valuable for the child to take part in that expression. Questions will arise. But, those questions are necessarily. And it’s okay if you don’t have the answers. Part of the reason why many of us DON’T take children to viewings and funerals is because we’re afraid of our children seeing us grieve … we’re afraid of our children seeing us in a state of weakness.

- Let the child see you grieve; it gives them permission to grieve on their own. “It will help the child to see the remaining parent, friends and relatives grieve. Grief shared is grief diminished…if everyone acts stoically around the child, he or she will be confused by the incongruity. If children get verbal or nonverbal cues that mourning is unacceptable, they cannot address the mourning task.”

- Gently help the child grasp the concept of death. Avoid vague explanations to the child’s questions, but answer each question as honestly as possible.

- Keep other stressing situations, such as moving or changing schools to a minimum; after the ceremonies, continue child’s regular routines.

- Be honest with the child about the depth of the pain he or she will feel. “You may say, ‘this is the most awful thing could happen to you.’ Contrary to popular belief, minimizing the grief does not help.

- Feed your child copious amounts of bacon and pizza. Because kummerspeck isn’t always a bad thing.

If You’re Dealing with Complicated Grief, Seek First Your Therapist, Not Your Pastor

Ernest Becker proposes that depressed individuals (specifically those depressed from death) suffer both doubt in their faith and doubt their value within their worldview. In other words, grieving people often doubt their religion and the God of their religion.

Kenneth Doka suggests that “one of the most significant tasks in grief is to reconstruct faith or philosophical systems, now challenged by the loss” (Loss of the Assumptive World; 49). All forms of grief, normal, complicated and especially traumatic grief produce doubts about one’s faith.

If you’re dealing with grief, your entire worldview is probably being challenged. It’s only natural that we attempt to seek council in such times; but, it might not be your best choice to seek your church and pastor’s help.

As many of you know, I’ve battled depression this past year; and while grief and depression are different, there’s many similarities. As I’ve adjusted to life with depression, there’s a number of things that I’ve learned and this is one of them: Most churches and pastors (and religious friends) aren’t equipped to recognize and address the depressed. We should not expect them to be equipped. But we do. They haven’t been trained to understand the psychosomatic nature of depression; nor have they a background in tasks of mourning or grief work models; the different types of grief and how each one should be approached.

And it’s okay to recognize the limitations in our religious community.

Today’s church speaks the language of affirmation, the language of light (cataphatic theology as opposed apophatic theology) to such a degree that doubt and darkness can sometimes be viewed as sin.

Depression, for some religious communities, is sometimes seen as a curse of God.

And grief, per the theology of many religious communities, is something that God might not feel, so neither should we (at least for an extended period of time).

And while some churches can be understanding of grief, and the doubt and depression that comes with it, few are prepared to understand how said grief, doubt and depression affects you.

We can become more course, more rigid and more … unacceptable. And, honestly, it’s possible that we do indeed become unacceptable for many churches, as our darkness and our doubt takes us out of the comfort realm for many within the church.

Indeed, many pastors recognize the limits of their training and can recommend professionals to help with your grief, etc., but some don’t recognize their limits. They can provide first or second level assessment (i.e., “you need some professional guidance”), but the deeper levels of assessment and counsel should be left to those grief specialists.

Unless your church or pastor has a professional background in understanding depression and/or grief, I think we do both our pastors, our religious friends and ourselves a great service by seeing someone who is professionally trained.

“You Working on Memorial Day?”

I’ve been finding myself at local hospital morgues nearly every day for the past month and today was no different. I parked my car behind the hospital in the little parking space that they have set aside for us funeral directors … a space where the dead are out of view from the living. I backed up to the ramp, put my car in park, pulled out my stretcher, punched the passcode into the security lock and parked my stretcher in front of the morgue door. From there, I took the long walk from the back of the hospital, through the halls and to the front, where I happened to pass the security guard. Usually he’s in his office, but today I must have caught him returning from fulfilling one of his many duties.

“You’ll be seeing me in a moment”, I said as I pass him along the hall. He’s responsible for opening the morgue and – if he’s feeling up for it — helping me with the transfer.

He’s about 35 years old. Nice. Professional guy. Takes his job seriously.

He stops the conversation that he’s having with a pretty nurse, turns around and starts walking with me to the lab that holds the paper work I have to fill out to officially release the body from the care of the hospital.

“I’ll let the lab staff know that I’m aware you’re here so they don’t have to page me.”

He lets them know, and starts his walk back to the morgue while I fill out the necessary paper work for the release.

I walk back and he’s at the morgue door waiting for me.

“Do you want some gloves, sir?” he asks.

I’m 30 years old, but I look more like 25ish. He’s probably 35. “Why would he call me ‘sir’?” I think to myself. This honorific was so natural for him too Pondering it a little more I suspect I know why, so I probe.

“You have the weekend off?” I ask.

“Yup.” He replies.

“You working Memorial Day?”

“Nope. Sittin at home, by myself, remembering.”

Feeling pretty confident that I’ve figured out why the whole “sir” thing was so natural for him, I ask my next question based on an assumption: “Are most of your co-workers ex-military?”

“Yes, sir.” He says. “Our boss is ex-army and hires us veterans.”

I reply: “Going from military to security is probably an easy transition for you guys.”

“Not for me. I was trained to take lives not save ‘em.”

At this point, the conversation moves from small talk to real talk. He’s starting to get personal and I can tell he wants me to know who and what he is.

“I’m an ex-marine. I was on the front lines of the first wave of infantry when we invaded Iraq.”

Out of the blue, without me probing, he say, “Lost some good fuckin friends.” In the morgue, in the context of death, he felt comfortable enough to show his raw emotions. It’s a sad testament to the difficulty of serving in the military when a young man of 35 feels this comfortable … this at home around death.

I lost a great uncle in World War II (who I obviously never knew), I lost a childhood friend in Iraq, but I’ve never served in the Military. I’ve attended a hundred military funeral services, some at Military Cemeteries and a half dozen at Arlington Cemetery, but I’ve never lost a close friend. My dad and cousin have blown taps for hundreds of veterans at their interment, but none of those veterans were my immediate family.

I know enough to know that while Memorial Day has significance for our nation, it doesn’t have the same significance for me as it does for this young man.

We pulled the body out of the morgue. I looked him in the eyes as I draped the cover over the corpse lying on my stretcher and I asked “What are you doing on Monday?” Tears started to well up in his eyes, so I pulled back any more questions.

He paused. Gathered himself. Looked at the ground and shook his head. Years removed from war, his emotion was still raw, and he struggled to constrain it.

I knew what he was saying. I’ve heard it said a thousand times. No words, but enough to say what you’re feeling.

After he gathered himself, and I listened for a couple minutes, it was time for me to go.

He helped me down the ramp to my car. I reached out my hand, shook his hand and said, “Thank you for your sacrifice.”

“I’d do it again”, he said.

This Memorial Day I’ll be remembering him as he sits in his house and remembers the ever haunting ghosts that will torment his life. I will remember and memorialize the sacrifice this young man has given as he carries the burdens of those who passed before their time.

We should remember that military deaths can also take the lives of those left alive.

10 Ways Funeral Directors Cope with the Stress of Death

Here’s 10 coping methods I’ve seen funeral directors use.

The first five are coping methods that are negative techniques.

The last five are positive coping methods. One or more of these methods MUST be used if a person is to stay in this profession AND maintain a healthy personal and family life.

NEGATIVE COPING METHODS

One. Displacement.

Funeral service is a business that is both uncontrollable and unpredictable. Since funeral directors can’t control death and death’s schedule, we attempt to control those things and/or people that we DO have power over. We too often take out our frustrations, fears and anger on those closest to us.

Two. Attack.

And we often displace those emotions on those closest to us with some kind of aggression. In an attempt to cope and find a sense of control in our uncontrolled and unpredictable world, we will often emotionally and verbally manipulate and control our family, co-workers, employees, associates and those closest to us, making us seem nearly bi-polar as we treat the grieving families that we serve with love and support and yet treat our staff and family with all the emotional turmoil that we’re feeling inside.

Three. Emotional Suppression.

We are paid to be the stable minds in the midst of unstable souls. We withhold and withhold and withhold and then … then the floodgates open, turning our normally stable personality into a blithering, sobbing mess, or creating a monster of seething anger and rage. During different occasions, I have become both the mess and the monster. The difficulty is only compounded by the fact that you just cannot make your spouse or best friend understand how raising the carotid artery of a nine-month old infant disturbs your mind.

Four. Self-harm.

We cope with alcohol. I know a number who attempt to waste their troubles away with a bottle.

Substance abuse.

Sexual callousness. The sexual philandering that occurred in Six Feet Under was not just for higher TV ratings.

Five. Trivializing.

Compassion fatigue happens to all of us in funeral service. If we can’t bounce back from the fatigue, we begin a journey down the road to callousness. Once calloused, we tell ourselves that “death isn’t as bad as ‘these people’ are making it seem.” Once we trivialize the grief and death we see, we can easily justify charging the hell out of the families we serve.

POSITIVE COPING METHODS

Six. Avoidance.

If this business is wrecking your life and the lives of those around you, then salvage what you have left and quit this business. Quitting doesn’t make you a failure. Quitting doesn’t make you weak. You know more than anyone that you only have one life to life. Live it to its fullest by doing something that breathes life into your soul.

Seven. Altruism.

Learn to love serving others. Probably the best means to cope with the funeral business is found in the people we serve. Love them intentionally and don’t be afraid to find joy in meeting their needs. Don’t be afraid to hear their stories and become apart of their family.

Eight. Problem-solve.

Don’t be passive with the burdens you carry. Actively attempt to find positive ways to deal with your burden. Exercise. Eat better. Take a vacation. Go out with your friends. If you can’t shed your burdens on your own, seek counseling. Find a psychologist. Find a psychiatrist. Talk out your problems with someone wiser than you.

Nine. Spiritual Community and Personal Growth.

Using religion as an opiate to ignore reality is something I speak AGAINST on a regular basis. Instead, seek a community where there’s faith authenticity. Find people who can encourage you with their love and support as you worship together and ponder the mysteries and truths of a better world.

Ten. Benefit-finding.

Emerson said, “When it is darkest men see the stars.” We try our best to deny the darkness of death; we consciously and unconsciously build our immortality projects, hoping that we can live immortally through them.

And then death. Weeping. Our projects come tumbling down. And it’s in those ashes, in the pain, in the grief, through the tears, we see beauty in the darkness. This is a perspective that funeral directors are privy to view on a constant basis. And, in many cases, the darkness can be beautiful.