Death

I Don’t Smile When I Embalm Bodies

***I originally wrote this post last fall***

The other day a contentious discussion brewed on my Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook page. And I’d like to address the topic in my blog’s forum.

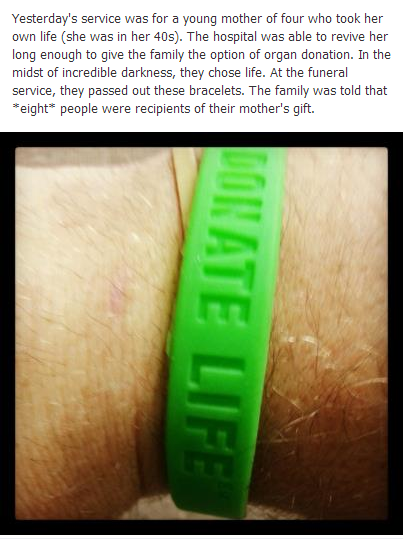

The discussion was kick-started when I posted this status:

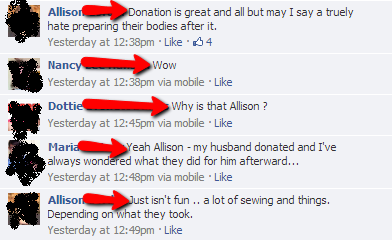

The second comment on the above status was from a fellow embalmer named Allison, who said this:

Allison’s initial comment eventual prompted this comment from a former embalmer named Kristie.

First off, let me say it’s possible for an embalmer to be both 100% for tissue/organ donation and not enjoy the process of preparing a donor. It’s possible for us to be both professionals and human. I’m one such funeral director. I am firmly and unequivocally a supporter of those who choose to find life in a tragic death, and yet when a donor body comes through the morgue door, it’s not Christmas morning.

I know that the best donors are usually young and they usually die from tragic (not necessarily violent) circumstances that leave their body in decent condition to be harvested.

I have immense respect for families who — in the midst of incredible tragedy and darkness — find a way to overcome their pain and chose life by allowing for the harvesting of a body they love so dearly. This act of donation is one of the few genuinely unselfish acts to be found in humanity.

Yet, while I recognize the intense moral beauty and life saving value of organ donation, I’m less than excited to embalm and prepare a donor’s bodies.

Each funeral home and funeral director is different. Some funeral homes are large enough to have shift work; still others are large enough to employ full-time embalmers, who basically embalm body after body all day. Some funeral homes have secretaries, prearrangement directors, at-need directors, full-time pick-up people, etc., etc. But for many of us small firms, we play role of embalmer, secretary, pick-up/livery person, funeral director, at-need director and pre-need director. We’re on call 24/7 and rarely have an uninterrupted holiday.

Our personal lives are not just blurred with our professional lives, they become one and the same, often resulting in sad endings. Divorce. Depression. Burnout.

Our pay doesn’t always justify what this profession takes from us. According to the BLS, the average embalmer makes $45,060, which isn’t bad until you consider that the salary often comes at the expense of our souls. I’ve worked 20 hour days. I’ve worked 100 hour weeks. Most months I get two days off.

I was up until 12 midnight writing this post and then at 3:30 AM I was called into work. I won’t be finished work until roughly 5:30 PM.

Here’s a picture of me at the nursing home at 4:40 this morning. The smile is real … the nurses were making fun of me for taking the photo.

And although this isn’t about me and the burdens I carry, I will say that my experience isn’t exceptional. The at-need demand, emotional and long hours take their toll on us as people.

So, when the heart is donated and I have to raise six arteries instead of one, I don’t smile.

When there’s bone donation, I don’t look forward to moving the Styrofoam rods around to make the appendages look natural.

When skin is grafted, I don’t smile when I’m cleaning the seepage off the floor.

When I get various liquids on myself because of the intrinsic messy nature of donor bodies, my face doesn’t crack a grin.

Unless I’m listening to stand-up comedy on the morgue’s radio, I don’t embalm bodies with a smile.

I appreciate Kristie’s assertion that she has never thought about complaining when preparing a body. And I appreciate that she always sees it as an honor. I will be the first to admit that Kristie is probably a better person and funeral director than I am. Maybe her suggestion to Allison (that Allison should find another profession) applies to me as well.

But, I, in contrast to Kristie, think it does us funeral directors well to be honest. Maybe not in a public forum like I’m doing now, but we need to recognize that we’re both professionals and human. We love to serve you, but there’s times when we too need to be helped. We need to fight that perception that to be a professional means being an unfeeling robot. We need to ask for help, sometimes we need to seek counselling. If you’re a funeral director and you don’t embalm donor bodies with a smile, it’s okay.

Alkaline Hydrolysis: Water Cremation and the “Ick Factor”

By Traci Rylands

Today’s guest post is a little graphic in describing how cremation works.

I recently wrote about the history of cremation in America and how it’s becoming more popular every year. However, an alternative form of cremation is gaining attention that’s truly different. Resomation, bio-cremation and flameless cremation are a few of the buzzwords used, but the scientific name for the procedure is alkaline hydrolysis (AH).

So how do you cremate a body without a fire?

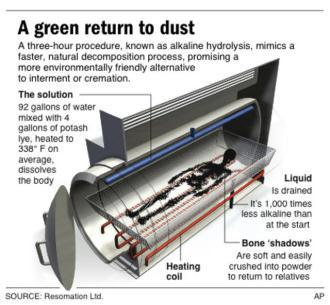

This graphic from Resomation, Ltd. explains the alkaline hydrolysis process. The company was founded in 2007 in Glasgow, Scotland by Sandy Sullivan. Ironically, AH is still not legal in the U.K. at this time.

Alkaline hydrolysis is a water-based chemical resolving process using strong alkali in water at temperatures of up to 350F (180C), which quickly reduces the body to bone fragments. Experts say it’s basically a very accelerated version of natural decomposition that occurs to the body over many years after it is buried in the soil.

AH was originally developed in Europe in the 1990s as a method of disposing of cows infected with mad cow disease. In England, AH for humans is not fully legalized yet. It’s usually referred to as resomation there because the commercial process was first introduced and trademarked by Resomation, Ltd. They received the Jupiter Big Idea Award (from actor Colin Firth, no less) at the 2010 Observer Ethical Awards.

Yes, that’s Colin Firth (aka Mr. Darcy) on the end. He presented the Jupiter Big Idea Award to Resomation, Ltd. at the 2010 The Observer Ethical Awards. The firm’s founder, Sandy Sullivan, is standing to his left. Photo courtesy of The Observer.

The University of Florida and the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota already use AH to dispose of cadavers. It’s not surprising that both states were among the first to legalize its use. The other states are Colorado, Oregon, Illinois, Kansas, Maine and Maryland.

But why would someone want to do what amounts to liquifying the body with lye instead of traditional cremation? Some people worry about the carbon footprint left behind by traditional cremation. AH is supposed to remove that problem.

In the traditional process that uses fire, cremating one corpse requires two to three hours and more than 1,800 degrees of heat. That’s enough energy to release 573 lbs. of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, according to environmental analysts. In many cases, dental compounds such as fillings also go up in smoke, sending mercury vapors into the air unless the crematorium has a chimney filter.

During AH, a body is placed in a steel chamber along with a mixture of water and potassium hydroxide. Air pressure inside the vessel is increased to about 145 pounds per square inch, and the temperature is raised to about 355F. After two to three hours, the corpse is reduced to bones that are then crushed into a fine, white powder. That dust can be scattered by families or placed in an urn. Dental fillings are separated out for safe disposal.

Anthony A. Lombardi, division manager for Matthews Cremation, demonstrates a bio-cremation (AH) machine. Photo courtesy of Ricardo Ramirez Buxeda/The Orlando Sentinel.

AH is purported to use about one-seventh of the energy required for traditional cremation. Some studies indicate that AH could save 30-million board feet of hardwood each year from cremation coffins. That’s very attractive to some people. However, one question remains. What happens to what’s leftover from the process (besides the ashes)?

That’s when the “Ick Factor” comes in.

Leftover liquids – including acids and soaps from body fat – plus the added water and chemicals, are disposed of through a waste water treatment process, according to John Ross, executive director of the Cremation Association of North America.

In other words, it goes down the drain like everything else.

“It’s very similar to the treatment of excess water from any (industrial) facility. In fact, it probably has less of a chemical signature than would you find (in liquids) coming out of most (industrial) plants,” Ross said.

Ryan Cattoni, funeral director at AquaGreen Dispositions LLC, offers the first “flameless cremation” in Illinois. Photo courtesy of Brian Jackson/The Sun-Times.

Still, the visual picture that creates is not very attractive. In fact, a 2008 article about AH said the thick coffee-colored liquid left behind resembles motor oil and has a strong ammonia smell. Not exactly something you want to put on a colorful marketing brochure.

AH became legal in Colorado in 2011. Steffani Blackstone, executive director of the Colorado Funeral Directors Association, spoke frankly about the “Ick Factor” when legislation to approve AH was being crafted.

“People seem to have objections when they actually think about that too long. They ask: ‘Well what happens? Does (the body) turn to sludge?’ And the thought of grandma being sludge is kind of disgusting to them.”

While currently legal in only eight states, the movement to make it so in others is real. In New York, the legislation became known as “Hannibal Lechter’s Bill.” New Hampshire legalized AH in 2006 but banned it a year later. In Ohio, the Catholic Church is a vocal opponent to AH and it has yet to be fully approved there.

Jeff Edwards, an Ohio funeral director who performed several AH procedures before being told to stop, filed a lawsuit in March 2011 against the Ohio Department of Health and the Ohio Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors after ODH quit issuing permits for AH body disposals. A judge ruled that ODH and the board had the authority to determine what is an acceptable form of disposition of a human body, as set forth in the Ohio Revised Code.

The cost of an AH machine can range from $200,000 to $400,000, depending on its size and capacity. That hefty price tag did not stop Anderson-McQueen Funeral Home in St. Petersburg, Fla., from becoming the first in the state to purchase one to provide AH to their clients. They refer to AH as “flameless cremation”.

Funeral home president and owner John McQueen said in a 2011 article that he planned to charge clients the same prices for AH cremations as the traditional ones, which can cost from $1,000 to $2,000.

Anderson McQueen became the first funeral home in Florida to offer alkaline hydrolysis to its clients. They call it “flameless cremation”.

So what do I think? In the end, traditional cremation sends its byproducts up into the air. AH sends them into the water for treatment. Which is better for the environment? I don’t know. I’m not fond of the idea of being burned up or liquified, especially the latter. The “Ick Factor” does give me pause.

A pine box in the cemetery still sounds better to me.

*****

Todays’ guest post is written by Traci Rylands of Atlanta, Ga. Traci writes, “I’m a photo volunteer for Findagrave.com, a database of cemeteries around the world. I enjoy learning about the stories of those individuals whose graves I find while educating others about death and dying.”

Please visit Traci’s blog, “Adventures in Cemetery Hopping.”

You can also like her blog on Facebook. And follow her on Twitter.

The Suicide Song I Wrote Back in 2004

This song is not meant to condone suicide. Rather, it is an attempt to empathize with those who struggle with suicidal thoughts, feeling and actions.

I wrote and sang this song back in 2004 for a class project in my funeral service program. There’s a video that goes along with it (and was a rad amateur vid for 2004), but the video is rather violent. Be forewarned that it not only contains violence, but it also has a number of heavy curse words. If you wish to bypass the video, you can just play the audio via SoundCloud.

The idea of the song is that some people’s lives are so messed up that they hope there’s a place where there is no existence. It was inspired by a friend of mine in high school, who was abused as a child and used drugs to blunt the pain. He was also raised in a Christian family and believed that his actions warranted hell.

His hope was that he could die and there would be neither heaven or hell, but simply nothing … a place where he can’t feel pain, hurt or even happiness.

The song itself starts at the 1 minute, 51 second mark.

Suicide Video from Caleb Wilde on Vimeo.

Ten Things We Use When Embalming

Some of these photos may be disturbing. All of these photos have been sourced either from the internet.

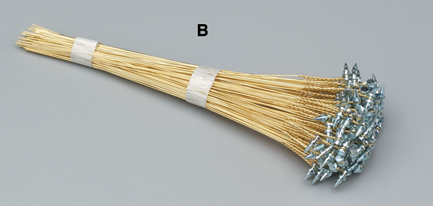

1. This is a needle injector, which is effectively used for mouth closure. We use this to set the features before we embalm. Once the mouth and eyes are closed (see number 2), then we can think about starting arterial embalming.

The needles are the shiny silver things attached to the shiny gold things (we only use two at a time):

One needle is anchored into the maxilla and another needle is anchored into the mandible. The wires that are attached to the needles are then twisted together until the mouth is “cranked” shut.

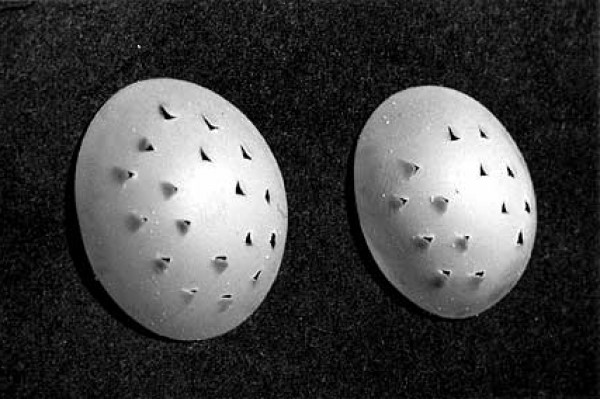

2. These round spiked spheres are called “eye caps”. They are placed under the eye lids and essentially grab the eyelids and hold them in place, keeping the eyes closed.

You can also use these as very small Frisbees.

3. These are examples of the scalpels that we use for embalming. They are sharp.

Many embalmers use the right carotid artery for embalming and the jugular vein for drainage of the blood. We use the scalpel to cut the neck and find said artery and vein.

The scalpels can also be used to cut other things, like steak and pork. But, it’s probably not good to use a used embalming scalpel on your steak. That’s an amateur move.

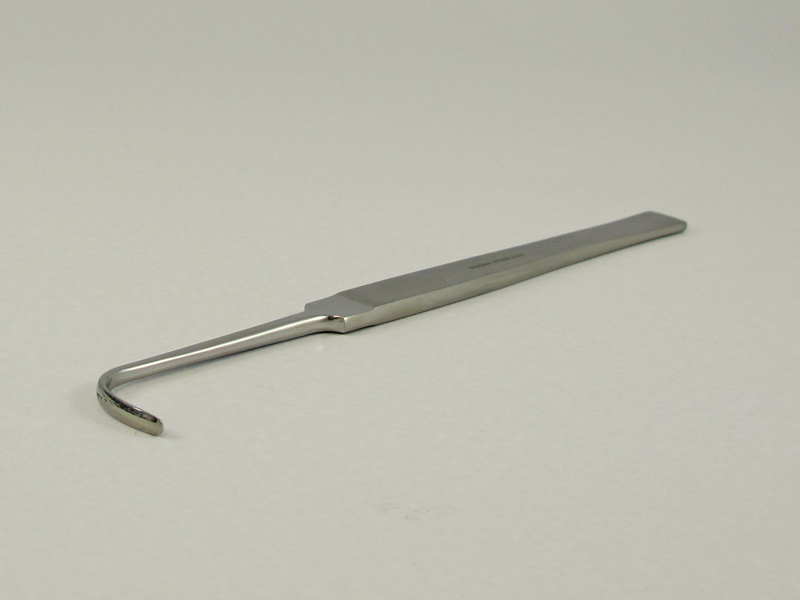

4. This is an Aneurysm hook.

We use this little guy to raise the artery and the vein out of the neck.

5. The arterial tube gets slipped into the incised artery.

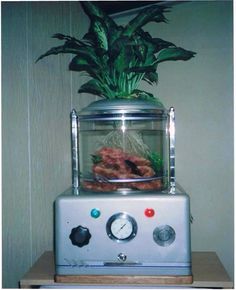

6. Embalming Machine (Drum roll please)

That black rubber tube gets placed onto the arterial tube and the embalming fluid is pumped into the arterial system.

That black rubber tube gets placed onto the arterial tube and the embalming fluid is pumped into the arterial system.

You can also use embalming machines for various other interests. Like a fish tank / plant holder. Or a punch bowl.

7. The drainage tube is slid into the jugular vein. When the embalming machine forces the embalming fluid into the arterial system, that fluid forces the blood out via the veins and the drainage tube.

8. Arterial embalming only reaches the parts of the body that are connected to the arterial system. The intestines, stomach, lungs, etc. are left relatively untouched. We then remove all the content of the stomach, lungs, etc. through a long needle like suction thingy called a “trocar”.

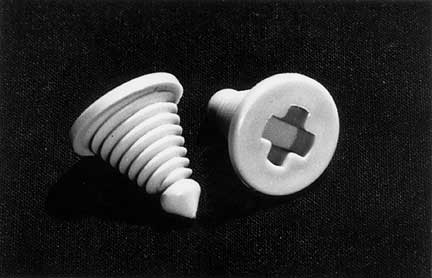

9. After the stomach, lungs, etc have been cleaned out, we then inject cavity fluid. After that has been done, we screw in a trocar button in the hole left by the trocar.

10. Finally, during this whole process, we use gloves. I prefer my latex gloves in the “Fierce Beige” color because it matches my personality.

Ten Reasons to Date a Funeral Director

Today’s guest post is by Lelial Thibodeau:

10. A funeral director knows how to stretch a dollar so far beyond capacity that extreme couponers would be seething with envy.

9. Funeral directors can get any stain out of any fabric.

8. Funeral directors understand the importance of paperwork. In triplicate. And filling it out is just par for the course. Tax season doesn’t compare to corporate budgetary reviews.

7. A funeral director is meticulously clean. From an unwelcome speck of dust on the end table to a mortifying bit of grit underneath near-perfectly manicured nails (this applies to the women and the men).

6. Have you ever not introduced a current flame to your family because you’re afraid your kin’s special brand of crazy will scare off any potential mate?

A funeral director is like a “crazy person whisperer.” They have to be just to get anything done. Bring on the monster in-laws.

5. A funeral director can’t be grossed out. Ever. There is literally nothing you could show one that would churn the contents of his stomach. This applies to noxious odours as well, so snag yourself a funeral director and feel at ease passing gas whenever the urge hits. They’ve smelled worse.

A lot worse.

4. Funeral directors are masters of illusion. Need to impress your boss at a dinner party? Stage your home for sale? Conceal something from your parents until you’re ready to deal, or the issue has been resolved? A funeral director thrives under one credo: Smoke and mirrors.

3. A funeral director understands how important it is to live for today, but plan meticulously for the future.

2. A funeral director is an expert at burying secrets. Yours are not as bad as you think they are, and the funeral director’s training ensures that your skeletons not only stay in their closet, but that the closet is sealed in a concrete vault under 8 feet of dirt and the paperwork has been properly “sanitized.”

1. A funeral director knows how to give you a delicious, full-body, invigorating massage that gets your circulation working overtime and leaves you feeling, well, like you’ve risen from the dead. How did we acquire this particular skill?

Don’t ask.

*****

Visit Lelial’s blog HERE