Death

Let’s Talk about Brittany Maynard

Despite all the negativity and divisiveness I’ve witnessed on social media concerning Brittany Maynard’s decision, I can’t help but think that she’s performed a modern day miracle: She’s enabled a large scale death conversation. She’s enabled us to think about end-of-life decisions. And hopefully, she’s inspired us to think about our own mortality.

Like with anything powerful, there’s always the danger of it being abused. And this conversation – the conversation about Brittany’s choice – is incredibly powerful. The abuse of the conversation looks like this: judgment towards Brittany Maynard. Let’s be clear. Brittany Maynard is dead. No amount of judgment will bring her back or reverse her decision.

You can disagree with her decision. That’s fine. In fact, that’s the point. The point is NOT for you sit by and ignore the Brittany Maynard conversation with formulaic clichés; the point is for you to deal with these thoughts internally … to let them settle into your being and find a home. The point is for you to think about how you want to die and what you would do if you found out that you were terminal. You’ll kill this very valuable conversation by getting stuck in judgment instead of asking yourself some very important questions.

Her death, whether you agree with it or not, has provided you with an opportunity to grab ahold of the end-of-life conversation, and help create a future for yourself where you know what YOU want.

Do you want palliative care?

Hospice care is a fantastic way of bringing terminally ill patients home while simultaneously relieving their physical and emotional pain through various forms of care. Is that something you want?

Do you want “death with dignity” laws in your state?

As of today, only Oregon, Washington and Vermont have “death with dignity” laws. If this is something you’re pro or against, it’s time to start voicing your opinion; and make sure you have legitimate reasons behind your opinion.

Have you thought about a living will?

Do you want to die with tubes hooked into your body, being sustained indefinitely by machines while your unconscious body lives on in a semi vegetative state? I don’t. And I’ve made it clear that I don’t. If you want the cyborg death and you don’t want anyone “pulling the plugs”, that’s fine … but either way you should probably make it official by creating a LIVING WILL.

At what point will you say, “I’m done with the medical ‘miracles’ and I’m ready to die”?

Perhaps one day you’ll be under dialysis, or have cancer that “might” be able to be fought through an undetermined amount of chemotherapy. How much are willing to tolerate? At what point are you ready to say, “enough is enough”?

If we look to answer these questions and refrain from judging Brittany’s very personal decision, value will come from Brittany’s death … and not more divisiveness. Because, according to Gallop, this issue IS the most divisive issue in America. It’s more divisive than abortion. It’s more divisive than LGBTQ rights.

And this is the reason it’s so divisive: we’ve given such little thought to end-of-life decisions that when we talk about “death with dignity” our reactions are almost entirely emotional. We react entirely out of anger, or compassion and we have little to say in the vein of reason. We talk about “slippery slope” or we use the “God argument” or we harken back to how we put down our dog when the dog couldn’t walk anymore (which really isn’t helpful to compare people to animals).

As I — and many others — have said, most Americans obsessively attempt to deny their own mortality. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross writes in “Death: The Final Stage”:

Dying is an integral part of life, as natural and predictable as being born. But whereas birth is cause for celebration, death has become a dreaded and unspeakable issue to be avoided by every means possible in our modern society. … It is difficult to accept death in this society because it is unfamiliar. In spite of the fact that it happens all the time, we never see it. When a person dies in a hospital, he is quickly whisked away; a magical disappearing act does away with the evidence before it could upset anyone. … But if we can learn to view death from a different perspective, to reintroduce it into our lives so that it comes not as a dreaded stranger but as an expected companion to our life, then we can also learn to live our lives with meaning— with full appreciation of our finiteness, of the limits on our time here.

Where does the end-of-life conversation go from here … after Brittany Maynard? I don’t know. Nobody knows. Because the conversation is partially up to you and me. Do we let the conversation die in judgment and emotions? Or do we take the stage that Brittany’s death created and talk about something we rarely talk about? Can we learn to make death the “expected companion”? I hope we take the stage. I hope we share. I hope we embrace mortality and the life that comes with it.

Before You Talk about Brittany Maynard’s Decision …

Sometime today (Sunday, November 2nd, 2014), Brittany Maynard took her own life under Oregon’s “Death with Dignity Act”. In the final paragraph of her obituary, she wrote, “It is people who pause to appreciate life and give thanks who are happiest. If we change our thoughts, we change our world! Love and peace to you all.”

While her act of “death with dignity” may or may not change the world, it will most certainly continue the social media discussion about euthanasia. Some of the discussion will be helpful and some won’t be.

Before any helpful discussion about Brittany Maynard takes place there needs to be some distinctions about forms and types of euthanasia. Often times, the difficulty in discussing euthanasia is when people confuse the different definitions.

Euthanasia Definitions

ONE: Active euthanasia: killing a patient by active means (Ex. injecting a patient with a lethal dose of a drug).

TWO: Passive euthanasia: intentionally letting a patient die by withholding artificial life support such as a ventilator or feeding tube.

And, there’s various forms of active and passive euthanasia:

ONE: Voluntary euthanasia: with the consent of the patient.

TWO: Involuntary euthanasia: without the consent of the patient, for example, if the patient is unconscious and his or her wishes are unknown.

THREE: Self-administered euthanasia: the patient administers the means of death. This is what is commonly called “suicide”.

FOUR: Assisted: the patient administers the means of death but with the assistance of another person, such as a physician.

The Slippery Slope Argument

What many people fear when discussing “physician assisted suicide” is the slippery slope … that once we allow assisted suicide, like Brittany Maynard’s, that we’ll begin to allow various forms of involuntary, active euthanasia (which is basically murder). Many – who fear authority in general – assume that once we legally give medical doctors the ability to determine life and death, that various ulterior agendas will be put into place.

That under the guise of “physician assisted suicide” we’ll systematically euthanize the supposed “unwanted” of society: “cripples”, the aged, the mentally ill and the marginalized.

To be clear, though, this isn’t Nazi Germany.

As it stands now, the idea of “physician assisted suicide” in Oregon’s “Death with Dignity Act” is both active and voluntary ONLY for those who are deemed terminally ill by the medical community.

The idea with Oregon’s “Death with Dignity Act” isn’t to create pain, it’s to end pain. This is an important distinction in the discussion. For Brittany Maynard, it’s her desire for quality of life over quantity that is inspiring her to make this act. The Los Angeles Times recently wrote this: “Right-to-death laws do not impose death on the very sick. Rather, they allow people who face imminent death to do so peacefully and without agony.” This “right-to-death” laws are ONLY applicable to those who voluntarily choose them.

The God Argument

Another element – and a VERY strong element – to this discussion is the religious element. Many firmly believe that God and ONLY God should choose when a person dies.

As one who holds a graduate degree in theology, I can understand the passion that resides in the hearts of believers. But — while the God element is the center of the believer’s life — we need to understand that – on a national and state level — this discussion is not being held in a church forum, it’s being held in a public sphere. And so the “let God decide when we die” arguments wouldn’t work outside the walls of our houses of worship.

Furthermore, the conversation is simply too complex for the “let God decide when we die” answer. With modern technology, the situation is often the case that humans do indeed decide. Whether it be passive euthanasia, like taking off life support and forms of palliative care (i.e. hospice), we often have to make the decision whether or not to continue to pursue medical support.

In fact, now more than any other time in human history, humans are presented with this choice: Do we want quality of life or quantity of life? Do we want to extend life through artificial means, or do we forego medical aid and die on our own terms? We are being asked to make decisions that were previously “left up to God.” We are, as we grow and expand our knowledge of the human body, determining more and more our fate. And as medicine has created “miracles” after “miracles” there has to be a point when we say, “I’m tired of the miracles. I’m ready to die.”

Entering the Discussion

The most recent Gallop poll found that 7 out of 10 Americans support the “dying on our own terms” form of euthanasia. Gallop writes, “Most Americans continue to support euthanasia when asked whether they believe physicians should be able to legally “end [a] patient’s life by some painless means.” Strong majorities have supported this for more than 20 years.

As advancements in medical technology continue and as support grows for “Death with Dignity” laws, this is a discussion that you’ll probably have around the water cooler at work, at home with your family and friends and online of your social media forums. And when we talk about people like Brittany Maynard, it’s important to remember the different terms and definitions. And it’s also important that we realize the slippery slope and God arguments aren’t the most helpful in public forums.

I believe that the center of a healthy discussion of euthanasia resides around ideas of community, an idea that I’ll probably develop in another blog post.

Whether you agree or disagree with Oregon’s “Death with Dignity” laws and Brittany Maynard’s decision, know that your voice is valuable to the conversation and that it’s time we think about this topic as thoroughly as possible, especially as one day these very questions may demand an answer from you as you face your own death.

This is a conversation that needs to take place in community and hopefully — instead of inspiring division — it will inspire better community and more active participation in taking care of our dying loved ones.

How to Speak the Language of Grief

You walk into a house full of fresh grief. It’s fresh because the death just occurred. Your best friend’s husband went out to the bar last night, drowned his hard day in hard drink and he never made it back home. Fresh. Because both you and your friend have never experienced death this close.

You open the door like you have so many times before, but this time the familiarity of the house is unexpected different, dark and lonely. What once housed parties, life and love now houses something you’ve never known before. Like a river, everything is in the same place it was when you last saw it, but this home has changed.

You see your friend’s children sitting on the sofa, staring into space.

You ask them, “Where’s your mom?”

And as you reach to hug them, they snap back to reality and whisper, “Upstairs.”

Each step brings you closer to what you know is only an apparition of your friend. The nerves build. Fear begins to build. You repress it as you ready yourself to meet your closest friend who has all of a sudden become someone you may no longer know.

“Can I come in?” you ask. No response.

You push open the cracked bedroom door and see the body of your friend collapsed on her bed, with used tissues surrounding her like a moat.

You tip-toe into the room, slowly sit down on the bed, and not sure if she’s awake or asleep, you reach for your friends shoulder and begin rubbing her back. Her blood shot eyes open, look at you and then, they slowly look through you.

You fill the weird silence with an “It’s going to be alright”.

“It’s not”, she whispers. “I’m alone with two kids and no job.” Her voice suddenly raises as anger courses through her body, “Why the f*** would he do this to me?”

The curse word chides you into recognizing that you’ve not only misspoken, but you’ve spoken too soon, so you decide to wait in silence. She starts to cry. You respond to her tears with your own. Even though you want to respond with words, you know this isn’t the time for words. There’s no perfection words here. There’s no perfect anything here. And so you wait.

You stay. Listen. Silence. You take her pain into your soul. Hours pass. She rises out of bed and makes the children dinner.

You’ve spoken, not with words or advice; not by trying to solve the problem; nor by placing a limit on your time. You’ve taken the uncomfortable silence, allow the grace for tears, for brokenness; you’ve allowed yourself to sit in the unrest without trying to fix it.

With your presence. With your love. In your honest acknowledgement of real loss, you’ve spoken the language of grief.

Although the language of grief is usually spoken in love, presence and time, sometimes it’s spoken in words. And when it is, here are five practical “do”s and “don’ts”

The “DON’T”S:

1. At least she lived a long life, many people die young

2. He is in a better place

3. She brought this on herself

4. There is a reason for everything

5. Aren’t you over him yet, he has been dead for awhile now

The “DO”S:

1. I am so sorry for your loss.

2. I wish I had the right words, just know I care.

3. I don’t know how you feel, but I am here to help in anyway I can.

4. You and your loved one will be in my thoughts and prayers.

5. My favorite memory of your loved one is…

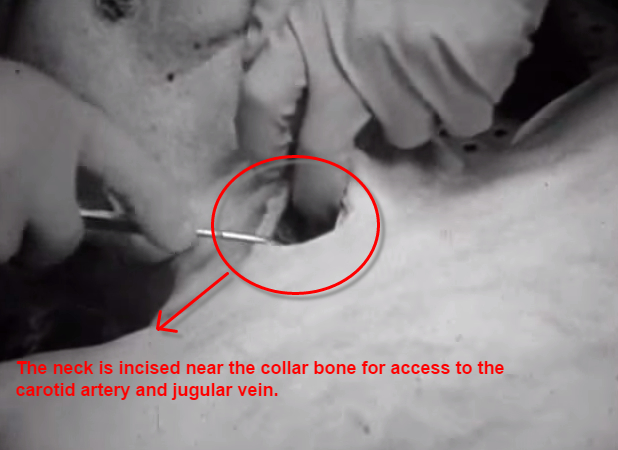

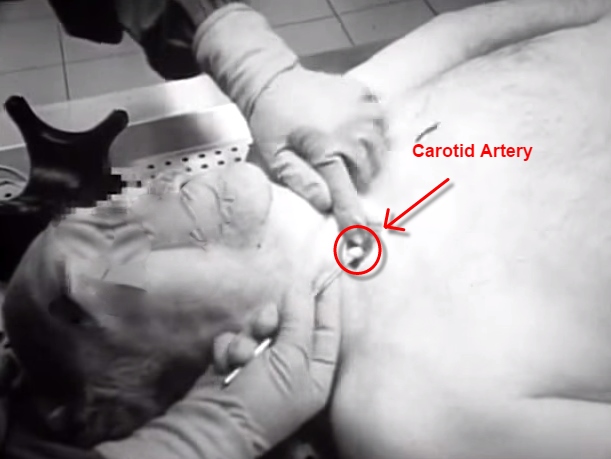

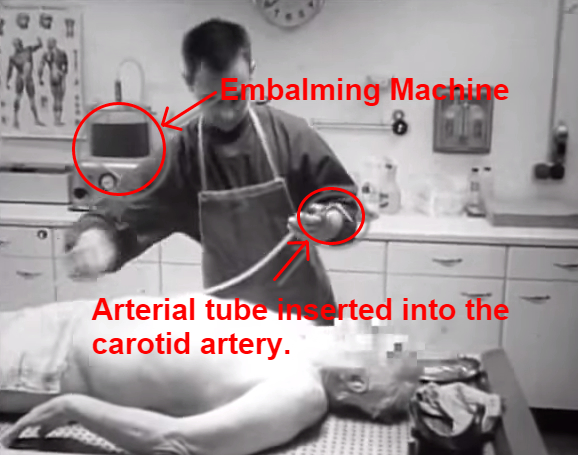

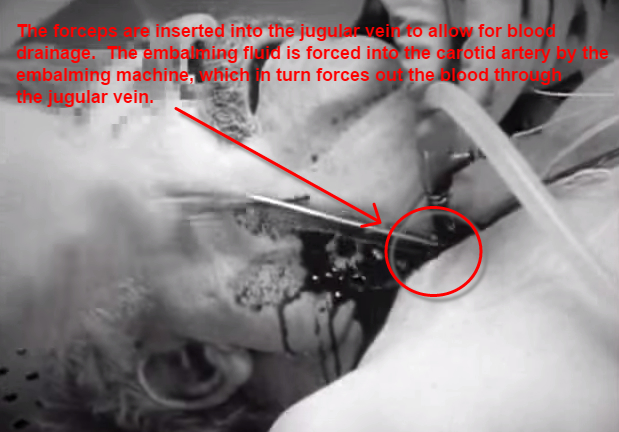

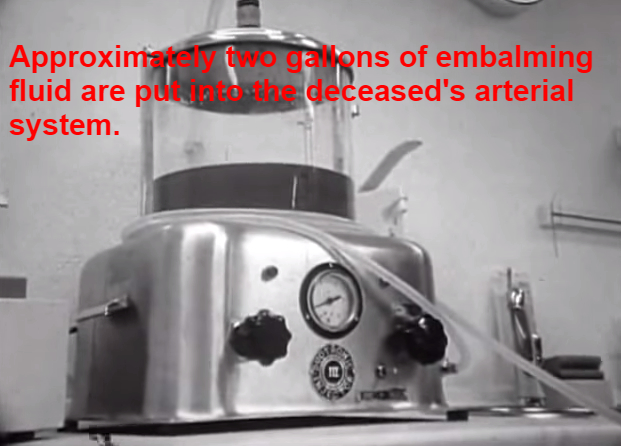

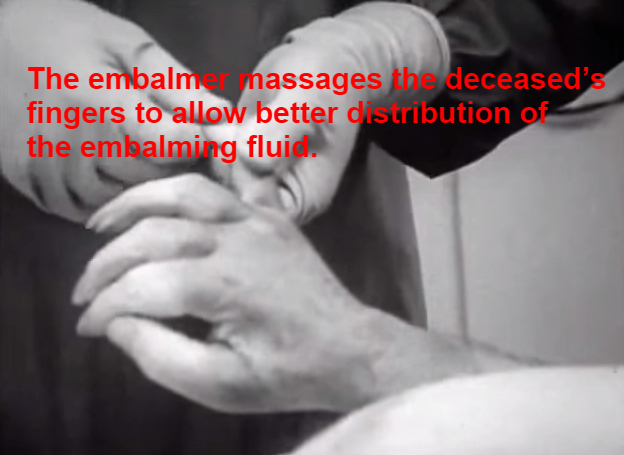

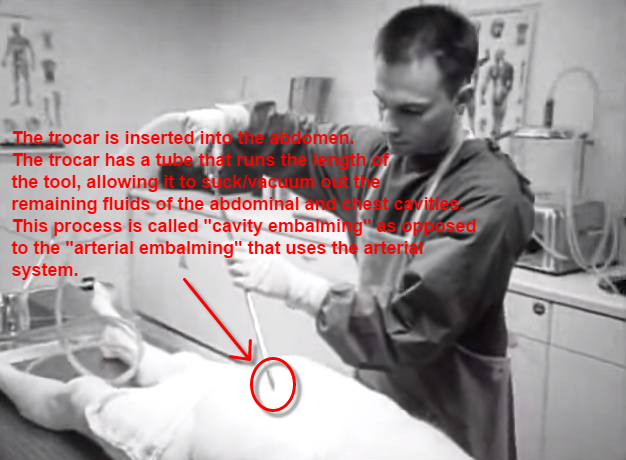

Eight Photos of the Embalming Process

WARNING: This post contains photos of the embalming process. If you are sensitive to photos of deceased persons and bodily fluids, please do not continue reading. The purpose of this post isn’t to salaciously satisfy your morbid appetite. My hope is that it can create a better (albeit fundamental) understanding of the process of embalming.

All of these photos have been sourced from the YouTube video “Modern Embalming Practice” by German embalmer Thomas Müller.

If you’re interested in the depth of the funeral business, this book will bury you six feet deep.

When Ebola Takes Your Soul: Reflecting on Funerals and Ebola

The CDC has already issued directions for morticians in the US regarding deceased cases with Ebola. It’s a “better safe than sorry” admonition that reads, “Do not perform embalming. The risks of occupational exposure to Ebola virus while embalming outweighs its advantages; therefore, bodies infected with Ebola virus should not be embalmed.” And farther, “Remains should be cremated or buried promptly in a hermetically sealed casket” (Via CDC).

Unlike most pathogens, the Ebola virus lives for an unknown period of time after a victim’s death (Via Scientific American). Unfortunately, the assumption that the virus dies along with the deceased has been a major cause of its spread in parts of Africa where touching and handling the body is a common practice for the deceased’s living family members. Some have claimed that ‘Up to 50% of victims catch Ebola at funerals’ (Via RT.com).

One case in point is that of the former Miss Liberia beauty queen, Shurina Weah. Shurina’s sister died and even though her sister’s death certificate ruled out Ebola, shortly after the funeral was held numerous family and friends contracted the virus, many become sick and some – including the beauty queen Shurina herself – died (although the family continues to claim that Shurina died of malaria).

And this is the problem that’s being presented in Liberia: Not all deaths are able to be investigated. Some could be due to malaria and some could be due to Ebola. Since no one knows for sure, all deaths are being treated as potential Ebola cases. And as of August, the Liberian government has declared that all deceased persons should be cremated (there are a few exceptions).

Now before you fall into the Ebola hysteria, remember that if you’re a US citizen you’re more likely to be killed by a falling vending machine than from Ebola. More people in the US have supposedly died from spontaneous combustion than from Ebola. And there’s less US citizens who have died of Ebola than have been married to Kim Kardashian.

For the Liberians, it’s a different story. Not only are people dying, but their very death culture is being circumvented by government decreed cremation. Traditionally, Liberian mourners bathe the body of the deceased, they clothe it and many even kiss the deceased as a token of farewell. Per TIME:

The government directive, while logical from an epidemiological aspect, has taken a toll on a society already traumatized by Ebola’s sweep. It denies communities a final farewell, and has led to standoffs with the Dead Body Management teams who must pick up the dead even as the living insist that the cause of death was measles, or stroke, or malaria — anything but Ebola. “We take every body, and burn it,” says Nelson Sayon, who works on one of the teams. Dealing with the living is one of the most difficult aspects of his job, he says, because he knows how important grieving can be. “No one gets their body back, not even the ashes, so there is nothing physical left to mourn.”

Monrovia’s mass cremations, which take place in a rural area far on the outskirts of town, happen at night, to minimize the impact on neighboring communities. For a while the bodies were simply burned in a pile; now they are placed in incinerators donated by an international NGO. There are so many that it can sometimes take all night, says Sayon. )

For many people groups, death rites are foundational for the community’s ethos … for the community’s soul. And when those death rites are denied, the community struggles for life. And while the US will probably never have a Liberian experience with Ebola, I can’t help but think how mandated cremation (and/or direct burial) would affect our death culture here in the states.

Actually, I’m not sure our death culture would change all that much. Because I’m not sure we have a death culture. Here in the U.S. and the West, we view death (per Philippe Ariès) as “invisible death”, where dying is handled by institutions and the dead are handled by “funeral professionals” who make it as clean as possible.

Unless we’re a part of a traditional religious community, I’m not sure many of us have death rites. And I know that few of us touch the dead like other cultures do. Few of us are involved in ritual washing and dressing of the body. Few of us see meaning in embracing the dead with a kiss … in fact, some probably see it as creepy. In the US, we already treat our dead as if they have Ebola.

Luckily for us in the Western world, our death culture doesn’t have a “soul”, so we don’t have to worry about Ebola taking it. If fact, government mandated cremation and direct burial might suit our death culture very nicely.