Death

A Death Positive Novel for Children (and Adults)

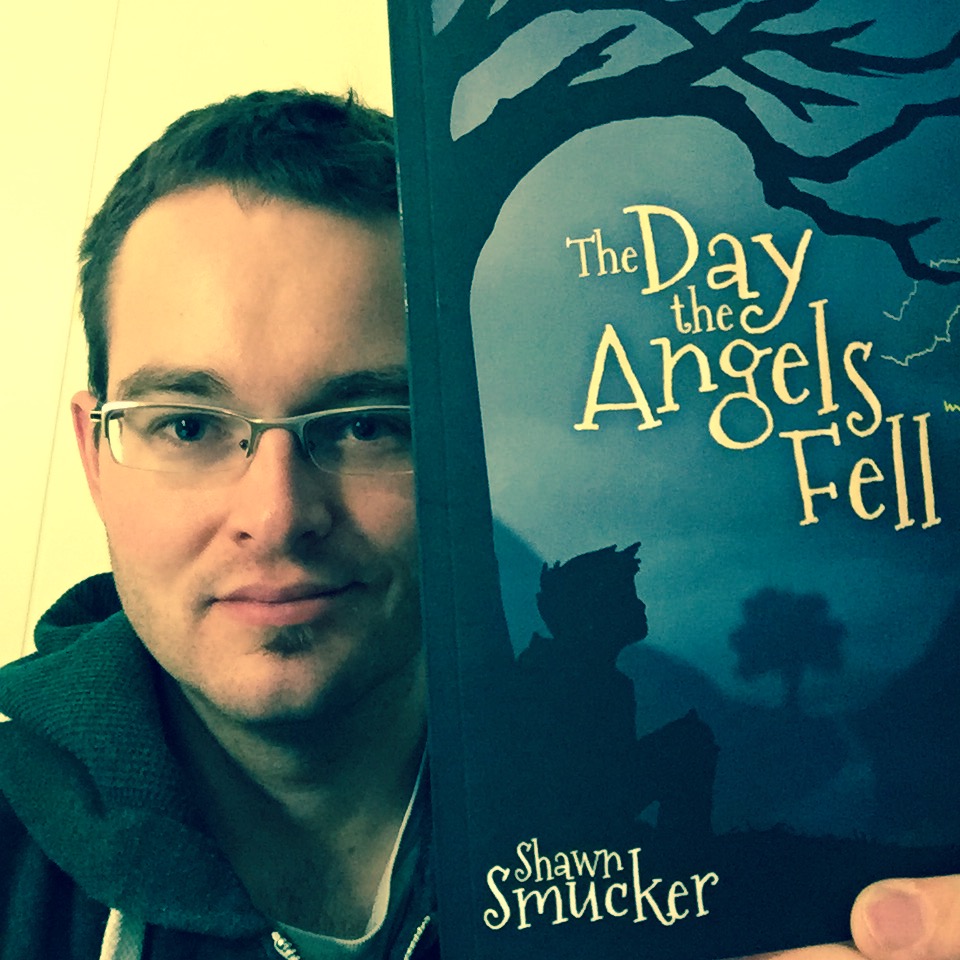

Full disclosure: This is a book review of The Day the Angels Fell. The author, Shawn Smucker, is my good friend. We’ve shared a number of early morning breakfasts and a couple kayaking trips. Shawn is a better person than I am. He’s kinder and more courageous than I’ll ever be. But that’s not entirely why I’m reviewing (and yes, promoting) Shawn’s book. I read Shawn’s book and I’m promoting it because I’m genuinely interested in its subject matter and I value its death message.

The Day the Angels Fell is a novel that explores an alternative narrative about death … a narrative that we rarely think about in America.

The common narrative that we’ve been told is that death is THE enemy. That death is so horrible we should do everything we can to shield ourselves (and especially our children) from its specter. That our mortality should be hidden away so that the rest of us don’t have to think about it.

The Day the Angels Fell explores the idea that death can be a gift. And not only does it explore that alternative narrative, but it does so with the intended audience being children (middle school on up to adult).

On some levels, The Day the Angels Fell compares with C.S. Lewis’ popular The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. That book – more so than the other Narnia tales – provides a way to help children understand and tackle big ideas like betrayal, sacrifice and forgiveness. The Day the Angels Fell tackles the big idea of death through a fantasy narrative that’s intended for children, but – like The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe – still resonates with adults.

The story revolves around twelve year old Sam and his friend Abra. After Sam loses his mother, he and Abra set out on a quest to bring her back. As he pursues a source of resurrection for his mother, he has to ponder the moral question: “If I find a way to bring her back, should I do it?”

It’s hard to talk to our children about death (hell, it’s hard to talk to adults about death). It’s even harder to do so without using flowery euphemisms and warm fuzzy answers. Perhaps the best way to do it is through a really good story. Shawn’s a storyteller (he’s written well over five books), and in this story, he finds a way to tell an alternative narrative about death for children and adults that isn’t wrapped in overused clichés.

*****

Right now Shawn dropped the Kindle edition price to $3.99 just for our Confessions of a Funeral Director community. It’s well worth the price of the purchase and the time to read it. You can find the paperback version HERE.

10 Things People Hate about Funerals

I motioned to where he should park his car in the funeral’s procession line. He threw it in park. Got out, straightened his tie, looked me in the eye and said, “I hate these thing.” I get told a variation of that line at least once a month. People don’t like funerals.

Here’s ten reasons why:

The Etiquette Questions.

Death is kind of like puberty. Sure, we know it’s coming. But no matter how much we’ve studied it in middle school and how much our parents have jokingly told us “it’s coming”, nothing can prepare us for the questions and awkwardness of it’s arrival.

And so when a funeral comes our way, so do a hundred questions:

Do I go to my co-worker’s mother’s funeral?

Do I bring my kids?

Do I send a card?

Can I pull out my phone and play Angry Birds during the funeral service?

WHERE IS THE FREAKIN RULE BOOK ON FUNERAL ETIQUETTE?

The Inconvenience.

Death acts like a god. It doesn’t care about your schedule. It doesn’t care that you have a major interview for a new job, or that you’re on vacation. It does what it’s suppose to do whenever the hell it wants to do it.

And funerals are the same way. They’re scheduled at the weirdest times … like 11 AM on Tuesday morning, when you were supposed to have your much needed spa treatment. And right in the middle of the college football game that you really, really wanted to watch.

The dress code.

You open up your wardrobe and you see sweatpants, a really short sundress, a couple t-shirts and khakis. But churchy dress clothes? Who dresses like that anymore?

So you think to yourself: Should I go out and buy a suit? Or should I just go to a funeral in a dress shirt/sundress, tie and bluejeans? You don’t want to overdress (or you’ll look like the funeral director) and you don’t want to underdress ’cause that’s just disrespectful. You look through your closet a little more and there in the back is your old prom dress … and the thought crosses your mind … “nah.”

What to say when you’re in the viewing line.

You jump into the viewing line. And you see one of your friends a couple spots up. You’re uncomfortable. She’s uncomfortable. You start talking about things … anything but the obvious. Before you know it your forget you’re at a funeral and you start laughing about some random poop story she’s telling. Like hysterically laughing. Then you look up and the rest of the viewing line is throwing some heavy Michelle Obama shade right at you.

The Body.

Oh Gawd. The body. The dead body. It’s a dead body. And I don’t even know this dead body. “I hate funerals”, you tell yourself.

The viewing.

Now that you’re right in front of the body you have this strange desire to touch it. You want to touch the hands, the face … something. And you remember, “It’s called a viewing … just look. It’s not called a touching.” So you keep your hands firmly planted at your side, hoping your hands don’t evolve a mind of their own and reach out and grab the deceased.

What to say to the family.

To Hug or Not to Hug

Maybe you know the son of the deceased … or maybe you just knew the deceased and not the rest of the family. But, there’s like 20 people in the receiving line … brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles and aunts. And you … you don’t know any of them.

Do I just hug everyone in the receiving line? Do I express my condolences to everyone; or do I just walk by and nod my head. And then there’s always that one person in the receiving line who likes to hug everyone that comes by. And when they do hug, it’s ten seconds too long and it’s sweaty and it’s weird.

So. Much. TOUCHING!

The Funeral Service.

The funniest things come to mind during a funeral. Really, they aren’t THAT funny, but because the funeral service is so solemn (and yes, at times boring), everything becomes sort of funny. So you bit your cheeks. Harder. It hurts now.

Existential Crisis.

After the whole depressing, horrible thing is finished, you realize, “OMG, I’M GOING TO DIE.” One day that will be me and that will be MY funeral service. Up until that point, you thought you were immortal. And now … gawd I hate funerals.

Speaking of Dead Moms…

Today’s guest post is written by Sara LeeAnn Pryde.

“Speaking of dead moms…” As if one can delicately work that into polite conversation. Which is why today is so impossible. Every year on January 29th – what would have been my mother’s birthday – my sisters and I wake up to our lives and feel numb. Angry. Empty. Anguished. And inconvenienced at having to pretend it’s just another day. And yet, it is. That’s the added insult to the injury of death, isn’t it? That the world should continue on when we can’t possibly?

For weeks leading up to our mother’s would-be-birthday, we dream of her. A dim, golden-haired waif whose face we can either recall with perfect clarity or never quite make out; so, we wake up on the 29th bloody tired, sometimes wishing we hadn’t, wishing we could stay beside her awhile longer.

I brew a pot of coffee, thick as mud, and trip over my accursed cats. How can they think of food today? Some 1200 miles away in California, my sister Brynn begrudgingly slaps the snooze button and buries her head. Not far south in a neighboring city, our sister Chelsie lifts her chunky, blue-eyed infant from the crib and feels her own burn with unshed tears. Ocean eyes, like our mother’s.

The clock is running and daily life proceeds as usual, but we three are frozen in time. We are thinking of our mom. We may want to talk about her, to say her name aloud… but our significant others have never met her, don’t remember what today is, or at least not what it means to us. We may want to hide from it altogether, and are grateful our friends and co-workers are as clueless as the bank teller or grocery clerk.

I sit down to write a tribute to my mother that will do my sisters proud, but I can’t find the words. How can I tell who she was to me? How can I tell why my own identity have splintered in her absence? How can I tell that losing her was more than just a tragic accident? How, especially when we haven’t reconciled that it was an accident at all? How can I breathe to life what is, some days, such a damn, diaphanous mystery?

I can’t.

Cindy was… Our mom was… magic. All smoke and mirrors and sparkle and magic.

And one day she just disappeared for real.

I gave up my memoir and went out instead to buy a bulk-sized bag of Jelly Belly Jelly Beans. They were mom’s favorites – especially the black licorice flavored. She and I would always fight over the licorice ones. The grocery clerk didn’t ask about my dead mom. He asked me about snowfall and if I’d had a pleasant new years’. I resisted the urge to punch him and cried in the car.

Back at home, I rummaged through my kitchen cabinets and art supplies and crafted a ridiculously cheerful Jelly Belly centerpiece on the dining table. Then I ate every single black jelly bean in memory of her.

Sometimes speaking of death isn’t necessary, and sometimes sharing it isn’t possible. We do as we do to get through. We eat the black jelly beans.

****

About the author: Sara LeeAnn Pryde is an enigma wrapped in a question mark behind a coat of winged eyeliner. She’s moonlighted as a massage therapist, optometric assistant, erotica photographer, small business owner and social media manager, but if you ask what she does for a living, she’ll laugh and ask you if that’s the most interesting question you can come up with.

Common Funeral Myths

© 2009 Stephan Ridgway, Flickr | CC-BY | via Wylio

Today’s guest post is from Funeral Consumers Alliance:

1. Embalming is required by law. Embalming is NEVER required for the first 24 hours. In many states, it’s not required at all under any circumstances. Refrigeration is almost always an alternative to embalming if there will be a delay before final disposition.

2. Embalming protects the public health. There is NO public health purpose served by embalming. In fact, the embalming process may create a health hazard by exposing embalmers to disease and toxic chemicals. In many cases, disease can still be found in an embalmed body. A dead body is less of a threat to public health than a live one that is still coughing and breathing.

3. An embalmed body will last like the “beautiful memory picture” forever. Mortuary-type embalming is meant to hold the body only for a week or so. Ultimately, the body will decompose, even if it has been embalmed. Temperature and climate are more influential factors affecting the rate of decomposition.

4. Viewing is necessary for “closure” after a death. When the death has been anticipated, family members have already started their “good-byes.” There is relatively little need to see the body to accept the reality of death. In fact, according to a 1990 Wirthlin study commissioned by the funeral industry, 32% of those interviewed found the viewing experience an unpleasant one for various reasons.

5. “Protective” caskets help to preserve the body. While gasketed caskets may keep out air, water, and other outside elements for a while, the body will decompose regardless. In fact, a gasketed or “sealer” casket interferes with the natural dehydration that would otherwise occur. Fluids are released from the body as it begins to decompose, and the casket is likely to rust out from the inside.

6. “Protective” or sealed vaults help to preserve the body. Nothing the traditional funeral industry sells will preserve the body forever. If there is a flood, however, such vaults have popped out of the ground and floated away. (Mass graves after the plague in England were ultimately found to be without health problems, according to the 1995 British health journal Communicable Disease Report. Burial in containers, however, often kept the disease “encapsulated.”)

7. Coffin vaults are required by law. NO state has a law requiring burial vaults. Most cemeteries, however, do have such regulations because the vault keeps the grave from sinking in after decomposition of the body and casket, reducing maintenance for the cemetery workers. Grave liners are usually less expensive than vaults. New York state forbids cemeteries from requiring vaults or liners, in deference to religious traditions that require burial directly in the earth. Those who have started “green” burial grounds do not permit vaults or metal caskets.

8. Vaults are required for the interment of cremated remains. Alas, with the increasing cremation rate, many cemeteries are making this claim, no doubt to generate more income. There is no similar safety reason as claimed for using a casket vault. Any cemetery trying to force such a purchase should be reported to the Federal Trade Commission for unfair marketing practices: 877-FTC-HELP.

9. What is left after the cremation process are ashes. When people think of “ashes” they envision what you’d find in the fireplace or what’s left over after a campfire. However, what remains after the cremation process are bone fragments, like broken seashells. These are pulverized to a small dimension, not unlike aquarium gravel.

10. Cremated remains must be placed in an urn and interred in a cemetery lot or niche. There is no reason you can’t keep the cremated remains in the cardboard or plastic box that comes from the crematory. In ALL states it is legal to scatter or bury cremated remains on private property (with the land-owner’s permission). Cremation is considered “final disposition” because there is no longer any health hazard. There are no “cremains police” checking on what you do with cremated remains.

11. It is a good idea to prepay for a funeral, to lock in prices. Funeral directors selling preneed funerals expect the interest on your money to pay for any increase in prices. They wouldn’t let you prepay unless there was some benefit for the funeral home, such as capturing more market share or being allowed to pocket some of your money now. Prepaid funeral money is NOT well-protected against embezzlement in most states. Furthermore, if you were to move, die while traveling, or simply change your mind—from body burial to cremation, perhaps—you may not get all your money back or transferred to a new funeral home. The interest on your money, in a pay-on-death account at your own bank, should keep up with inflation and will let you stay in control. Please note: We’re seeing more low-cost, low-overhead funeral operations opening up, so prices may go down in the future in areas with open price competition.

12. With a preneed contract, I took care of everything. There are over 20 items found on many final funeral bills that cannot be included in a preneed contract because these items are purchased from third parties and cannot be calculated prior to death. Extra charges after an autopsy, clergy honoraria, obituary notices, flowers, the crematory fee or grave opening are typical examples. All such items will be paid for by the decedent’s estate or family, in addition to what has already been paid for in the preneed contract.

13. Insurance is a good way to pay for a funeral. Interest accrued by an insurance policy may be outpaced by funeral inflation and is generally less than what is earned by money in a trust. When a funeral is paid for with funeral insurance, either the funeral director will absorb the loss (and many reluctantly do)—OR figure out a way for your survivors to pay a little more: “The casket your mother picked out is no longer available. You’ll have to pick out a new one, and the price has gone up.” If what you have is life insurance, not funeral insurance, it may be considered an asset when applying for Medicaid. In that case, you’ll have to cash it in, getting pennies on the dollar. The same may be true if you’re making time payments on your funeral insurance, and, in hard times, you decide to stop making payments. In fact, the company may be able to keep everything you paid, as “liquidated damages.”

14. If you have a Living Will you won’t linger on with a lot of feeding tubes and extraordinary measures. One of the findings from a major study supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation was that hospitals often fail to comply with Living Wills. The Living Will is more likely to be honored when there is an aggressive family member to intercede, especially if that person also has a Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care.

Copyright © FCA

*****

Funeral Consumers Alliance is a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting a consumer’s right to choose a meaningful, dignified, affordable funeral.

You can visit their website HERE.

To Bury a Father

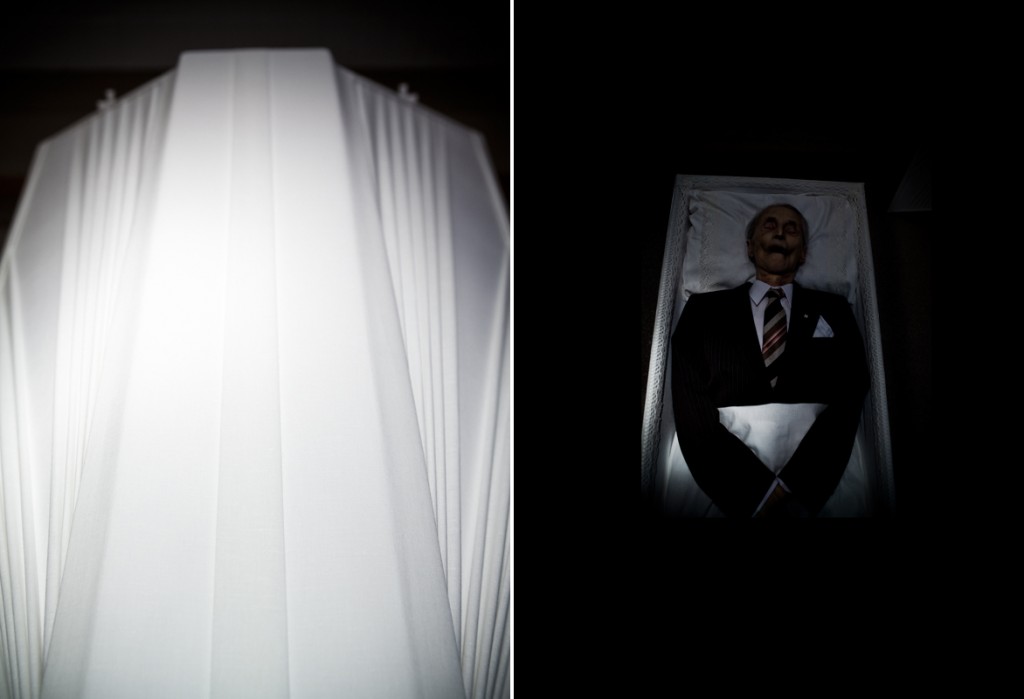

This post is by photographer KIMMO METSÄRANTA. It is used with Kimmo’s expressed permission.

My grandfather died in the spring of 2014. It didn’t come as a surprise to anyone. During the last two years he didn’t respond a lot, he wasn’t present. I don’t know if he thought about dying, was he expecting it, afraid of it. I don’t think so. He was 87 years when he died.

My sister and I prepared him for his coffin with the mortician. We dressed him into his best suit, combed his hair. It felt like a last favour for him. Maybe I was trying to compensate the fact that I visited him far too seldom. I don’t have a clear conscience about that.

Most people in Finland don’t know that you can go dress the deceased. And if they did they probably wouldn’t do it. Death is still a taboo. You are not supposed to talk about it, little alone to show pictures about it. I don’t know why this is. Maybe we don’t want to be reminded of the fact that none of us is immortal.

My grandfather and I were not close for many years due to the fact that he and my grandmother lived far away. Only after he ́s condition started to deteriorate did I make more effort to visit them. The visits were not easy. He didn’t have his hearing anymore and my grandmother had no short term memory. She would ask the same questions again and again and he would sit in the table and smile, not knowing what we were talking about. But he seemed pleased that he still recognised me.

The moment of preparing my grandfather was beautiful. Time seemed to come to a halt. There was no hurry, nothing outside the present moment. All the memories felt stronger, more concrete. During the years I had photographer him on many occasions, he always had this amazing feeling of presence. This was our last shoot together although in some sense he was no longer here. Merely a shell was left. I took photos for a few minutes, then I closed the coffin with the mortician. That was that. The last time I saw him.

Later as I watch the pictures he seems to be at ease. And there still is that sense of presence. In some way I feel a lot closer to him now than I did before.

2014

back to work

You can see more of Kimmo’s work HERE.