Death

Presidential Grief: Five Stories of Death in the White House

Today’s guest post is written by Chad Harris:

The presidency of the United States often seems like a job filled with perks, and we so often think of the man and the office as a single entity. They often have to lead the nation in its grief response to tragedy – after all, to whom do we look in times of crisis? The president. But let’s not forget there is an individual behind that title – and often, presidents and their families have had to cope with grief and tragedy on intensely personal levels while residing behind the gates of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. In honor of Presidents Day on February 16, when our nation honors all those who have taken up the mantel of national leadership, here is a brief look at a few presidents and their families who knew the sting of grief and death all too well within the walls of the White House.

Andrew Jackson (1829-1837): The president known as “Old Hickory” had a long, storied military career that included a decisive victory at the final battle of the War of 1812, the Battle of New Orleans – two weeks after the war had officially ended. His personal life was no less full of controversy, having married his wife Rachel in 1791, only to have it declared a bigamous union, leading to their divorce in 1794. After things were cleared up, the pair remarried soon after, and would remain married until Mrs. Jackson died on December 22, 1828 – 72 days before her husband assumed the presidency and months after the death of the couple’s adopted Native American son Lyncoya in early 1828.

Franklin Pierce (1853-1857): A lesser-known chief executive and widely proclaimed one of our nation’s most incompetent presidents, President Pierce battled for years with substance abuse issues, and was by no means a stranger to grief. His oldest son, Franklin, died three days after birth, while middle son Frank Robert died at age 11 from typhus. The Pierces left New Hampshire in January 1853 to prepare for the president-elect’s inauguration on March 4. On January 6 – 57 days before Pierce would become president – the train carrying the future First Family derailed and tumbled down an embankment. Most on the train only suffered minor injuries, but there was one fatality – the Pierce’s youngest son, Benjamin, was beheaded in the accident. Pierce’s presidential years are largely seen as a mere footnote by most historians, but tradition was born out of the family’s grief: the placement of a Christmas tree in the White House, where there has been one every year since 1856.

Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865): Not only did President Lincoln have to guide the nation through the struggle to reunite a nation torn asunder by the Civil War, but he also had to try and hold his family together when youngest son Willie died of typhoid fever in 1862. The 11-year-old’s funeral was held in the White House, and for years afterward, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln would often converse with her dead son. She would go on to outlive three of her four children, as well as her husband, who was assassinated in her presence. She was committed to an institution for a year, suffering from what was likely depression exacerbated by bereavement overload and very complicated grief. She would spend the last decade of her life largely hidden from society.

John F. Kennedy (1961-1963): President Kennedy and his wife Jacqueline brought a youthful energy to the White House that many Americans were completely enamored with, awed by the seemingly perfect, beautiful couple and delighting in the antics of their young children, Caroline and John Jr. (who was born three weeks after his father’s election to the presidency). Unbeknownst to many, Mrs. Kennedy suffered a miscarriage in 1955 and gave birth to a stillborn daughter in August of 1956. On August 7, 1963, the First Lady gave birth to a son, Patrick, while the family was vacationing in Massachusetts. For 39 hours, doctors tried to keep the baby, who had been born 5 ½ weeks early, alive while the president kept a nearly uninterrupted vigil, watching over the youngster. Patrick died on August 9. Within 3 ½ months, the First Lady would again find herself mourning – this time for her husband, who was assassinated on November 22, 1963, in Dallas. The president, Jackie, Patrick, and the couple’s stillborn daughter are all buried next to one another in Arlington National Cemetery.

This is but a sampling of those who experienced the death of a child or spouse before or during their tenure in office. Six other first ladies besides Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Kennedy had to mourn amid the tears of a nation when their husbands died in office, whether of illness (William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, Warren G. Harding, and Franklin D. Roosevelt) or an assassin’s bullet (James Garfield and William McKinley). The White House may be one of the most secure homes in the world, but not even high-tech security can insulate presidents and their families from death and the resulting wave of grief.

*****

About the author: Chad Harris is a graduate student at Hood College in Maryland, where he is pursuing a master’s degree in thanatology, as well as coursework in gerontology. He also holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Central Arkansas, as well as a master’s degree in social work from Case Western Reserve University. He is currently researching the role of mass media in shaping people’s perceptions of death and the impact of media coverage on grief and mourning, with the hopes of helping promote more responsible coverage of tragic events.

10 Ways Children Can Be Involved in Funerals

There’s a concept called “disenfranchised grief.” The idea is that there’s certain types of grief relationships that society either downplays as less important or outright ignores. For example, the grief over a pet’s death; the death of an ex-spouse; and — a big one — miscarriages and stillbirths. But perhaps the biggest segment of disenfranchised grievers are children.

Children are disenfranchised for two reasons: their parents haven’t confronted death on a personal level and have become so frightened of it that their natural reaction is to shield their children from the perceived “monster of death.” And two, parents simply repeat the evasive cliches and religious euphemisms they’ve been taught, leaving kids to believe that the deceased is just “sleeping” or “gone to be with the angels.” Cliches act as an unintentional defense mechanism that often keep the children from full death confrontation and thus grief.

I believe that allowing children to be a part of the death conversation and allowing them to be a part of the funeral gives them permission to be a part of the community of grief.

Many of the following suggestions depend on the age, maturity and level of comfort the child has with death. Certainly you never want to force a child to confront death. But if they want a role in the funeral process, here’s ten ideas (many of which were sourced and screen captured from the Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook community):

1. Presence.

Involvement doesn’t necessarily mean DOING something. Involvement can simply mean BEING present in the context of community. When it comes to death, perhaps the greatest form of involvement is presence. And perhaps the easiest way to determine if your child should or shouldn’t be present is to simply ask them.

As a funeral director, I’ve seen children of all stages at the deathbed of the deceased, many have been brought while their parents made the funeral arrangements, they’ve been present for private viewings, present for public viewings and present for the funeral. It’s okay (maybe even healthy) to involve your children in as much of the funeral process as you want them to see.

2. Burial Involvement.

3. Greetings.

Have them great the family and friends that are coming to the funeral. Usually there’s a stand with a registrar book and memorial cards. I’ve seen young children take charge of getting people to sign in and handing out the memorial cards. It’s a very positive and fulfilling role for the children.

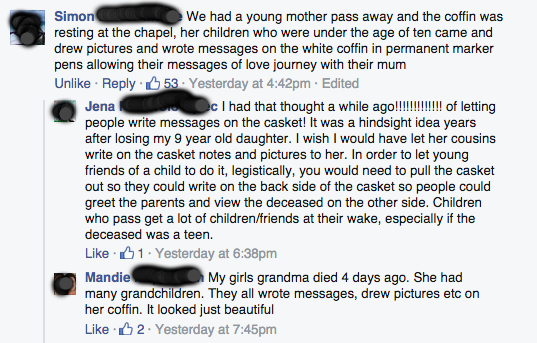

4. Artwork

5. Sing Some Songs.

6. Hand Out Flowers at the Graveside.

Sometimes flowers will be handed out at the graveside as a “final token of remembrance.” It’s a beautiful thing when children hand out the flowers.

7. Junior Pallbearers.

8. Tactile Death Confrontation

9. Eulogize the Deceased.  10. Bedside Care.

10. Bedside Care.

Nine Benefits of Hiring a Funeral Director

© 2014 Raina Gauthier, Flickr | CC-BY | via Wylio

There’s a lot of “death hacks” and DIY options that all but eliminate the need for a funeral director. But, this doesn’t mean funeral directors are outdated and unneeded. Like taxes, wedding planning, buying a house or even giving birth, there’s a range of symbiotic DIY options and professional involvement. While it’s usually possible to have a DIY funeral, funeral directors are beneficial during the death process.

Here are nine benefits to hiring a funeral director:

1. Documents, Applications, Paperwork, etc.

We’re kind of pros at this stuff. From death certificates to burial permits, to military marker applications to Social Security reporting, we can fill them out like Brian Williams can make up war stories.

2. Good hugs.

I’d like to believe I give some of the best hugs. I’ve probably hugged more people than Hugh Heffner has slept with (okay, that might be an exaggeration). I’ve perfected my squeeze, my hold length (not too longer and not too short) and I know the right time to give a little kiss on the cheek. Yes, we give hugs to people who don’t hire us, but we give more hugs to the people that do.

3. Logistical Stress Relief.

When my wife and I got married we were young and situated in the poverty bracket. Our wedding was put together by the good will of our family and friends. We — my wife and I — did much of the logistical and orderly work ourselves before and during our wedding day. It’s hard to look back at our wedding and say, “Oh yeah, we had a blast” because we were the one’s pulling together the last minute details and making sure the wedding orchestration was on point.

Weddings are stressful. So are funerals. To have a wedding planner would have helped the joy of our wedding day. To have a funeral director can often help the grief of death.

4. Stable Minds for Unstable Souls.

I don’t really like the term “funeral director” because I believe our role should be less directing and more guiding. We can do either, but our experience, the fact that “we’ve done this” a lot allows us to provide you with a stability reference point when you’re at your most unstable moment. In some sense, we are like hiking guides. We can help you trek through some of the stages of a foreign environment.

5. Reference Gold Mine.

We know people. Pastors. Celebrants. Insurance Companies. Estate lawyers. Newspaper contacts. Flower shops. Funeral catering companies. Bagpipers. Organists. Irish Dancers. Bar tenders. VA Benefits Personnel.

6. At Need Attention.

When a death in your family occurs, your mind can become a crazy whirlwind of thoughts and feelings. Rarely do those thoughts and feelings pop into your mind in a nice orderly fashion. They come early in the morning, late at night, etc. and we’re there — usually a phone call away — from helping within our capacity.

7. Product Availability.

Yes, Walmart sells caskets. But we’re like the Walmart of funeral products: we’re that one stop shop for all things funeral. And if we don’t have the urn or casket or thing you’re looking for, we usually have the connections to those who do.

8. Back Rubs.

The code phrase is “Grin Reaper”. If you say that phrase to any funeral director, we’ll be obligated to give you a back rub that will rid your body of grief pain.

9. Embalming.

If funeral directors think embalming is the very best we have to offer the grieving masses, we’re missing out on our true potential.

But, with that said, when a death is tragic and the body has been disfigured and there’s a desire to see the deceased in a less disfigured state, embalming and restorative art offer a real value to the bereaved that only we can provide.

Five Ways Funeral Directors Can Bully Their Customers

© 2006 Gregory Veen, Flickr | CC-BY-SA | via Wylio

There are bullies in every business. In the funeral industry — because of the customers emotional vulnerability and the fact that the purchases are often of high value — there’s a greater opportunity for bully funeral directors to exploit their customers.

Back in elementary school, I learned a lesson about bullies: they gain their value off provoking emotional reactions and thrive off feeling a sense of power over you. Take away the power, take away the emotional reactions, and — they might still be mean — but they no longer have the power and value they so desperately seek.

While I continue to believe that the majority of funeral director are honest, empathetic and service oriented, some funeral director will bully their clients into more expensive funerals, especially pricier vaults and caskets purchases. While the elementary school bullying has evolved, the intention is still the same: to exploit emotions and gain power.

Here are five ways — and some cliche lines — funeral directors use to manipulate their customers into upsells:

Creating false and/or unsubstantiated expectations:

If you buy this vault, your husband will be protected for ALL ETERNITY.

Buying this casket will ensure that your son will stay in perfect shape for the next hundred years.

Guilt Trip.

I’m sure he was the best dad ever. He certainly deserves the best casket.

I wouldn’t put my dog in that vault.

You may not have been able to provide the best stuff for your son in life, but you can give him the best in death.

Emotional Manipulation.

I hate the thought of worms eating my loved one’s flesh, which is why this sealer vault gives me peace of mind.

Can you put a price on your peace of mind?

Religious Persuasion.

Jesus Christ had a sealer tomb.

Insects, mice, nothing can get into this casket except the Lord Jesus Christ on Resurrection Day.

(I’ve actually heard of funeral directors who dissuade customers from cremation with religious reasons. Yes, Islam and Judaism traditionally prohibit cremation, but all Christian traditions [except for Eastern Orthodoxy] allow for the cremation of the deceased’s remains).

Aggressive Sales Tactics.

THIS is the casket you need.

I KNEW your father and I KNOW that your father would want this vault.

You don’t want a CHEAP casket. Do you?

*****

As I’ve said before, if you EVER feel like you’re being manipulated or exploited by a funeral director, fire your funeral director. Walk out and tell them, “I’m taking my business somewhere else.” Death causes us to be emotional vulnerable and the last thing you need is a funeral director attempting to weasel his/her way into your wallet.

If you’re already the type of person who is susceptible to manipulation (you’re a “people pleaser”, you lack assertiveness, low self-esteem, etc.), it’s smart to bring someone with you when you to make arrangements. The last thing you need while coping with a death is to feel like you’ve been exploited by a funeral director.

Pitfalls of Kubler-Ross

Today’s guest post is written by Chad Harris:

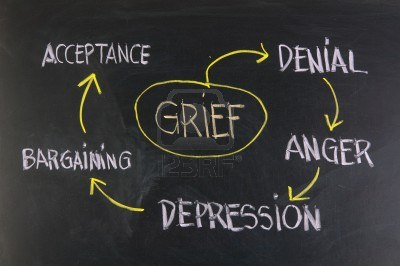

Ask most people what they know about grief, and they will likely mention that it’s made up of 5 stages:

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

Makes it all sound neat, tidy, and orderly, doesn’t it?

Problem is, grief is messy!

Kubler-Ross did not originally intend for her model to be widely accepted as a model of grief and loss – in fact, her stage theory came out of her work with those who were actively dying, not those who were grieving the death of a loved one. Yet, the medical establishment and the general public embraced this model, in no small part because it seemed intuitive and orderly. However, classifying them as stages diminishes the fact that people may not move through these thoughts, feelings, or actions in order. In fact, they may skip ahead, work through them out of order, go backwards between stages, or even repeat stages. Perhaps most troubling, such a model makes those around the griever more likely to think they know what the person is going through – and that they can helpfully tell the person what to expect next.

Did I mention that this is rarely the case since grief is messy?

In the years since Kubler-Ross’s work started gaining ground in the late 1960s, a number of alternate theories have been proposed, and while there is no one grand unified theory of grief – and no one theory can explain everyone’s grief (since it’s messy!), one that has gained much traction and that helps provide meaning to the rituals of mourning through which we express our grief is found in the work of psychologist Dr. J. William Worden.

In his 1982 book “Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy”, Worden proposed that when we are faced with grief, we make sense of that grief (as much as is possible) and find our way back to some semblance of daily functioning through the act of mourning – our public “face” of grieving a death.

Worden proposed that each grieving person undertakes four tasks in order to process the death of someone meaningful, and by doing so, a griever comes closer to finding their way to their new normal.

Worden’s Four Tasks of Mourning

- Accept the reality of the loss.

- Work through the pain of grief.

- Adjust to an environment in which the deceased is missing.

- Find a way to form an enduring connection with the deceased while embarking on a new life.

Accepting the reality of the loss is vital. In order to heal, we must first understand that we’re hurting and that something is not the same. Sadly, growth and change is often spurred by discomfort. While there are a number of ways to begin to either accept the reality ourselves or to help others, among the most effective are funerals/memorial services and using words that aren’t cloaked in platitudes or euphemisms. The loved one in question didn’t get lost, nor did he or she expire like a carton of milk. He or she died. People die. It’s part of the human life cycle, and it’s important to embrace this fact.

Working through the pain enables us to not feel stuck and to begin to find some level of healing. It keeps us active, engaged, and moving ahead, helping to keep us from feeling stuck. Will we feel stuck sometimes? Of course! As long as we remain open and honest, though, we will make our way forward in our own time and in a way that makes sense to us.

Adjusting to an environment in which the deceased is missing does not mean forgetting the person existed. It merely means understanding that our worldview has been irrevocably changed, and though the person is no longer physically present, our memories will keep them with us.

Finding a way to create an enduring connection means honoring the person through our actions and carrying them with us in our hearts. Pictures, favorite books, or even volunteer activities that you do in their memory can help create this lasting, meaningful connection. As long as we hold the person close to us and honor that connection, they are not lost to us, even if they may not be physically present.

Worden’s tasks allow grievers to move ahead at their own pace. Yes, they are placed in some semblance of order, but they are tasks, and not merely things that happen to us or thoughts, feelings, or emotions we are carried through in a passive manner – which is how a reliance on the Kubler-Ross model can often make people feel. Worden’s tasks are active. Worden’s tasks empower grievers, giving a greater sense of control than models like Kubler-Ross’s.

Worden’s model isn’t perfect, of course. It appears quite linear and it may also seem as though there is no room for sliding backwards amid the tasks. After all, grief is messy, and a griever may often feel waylaid by what Dr. Therese Rando calls “sudden, temporary upsurges of grief”, or STUGs. No matter how long it has been since our loved one has died, we are going to have moments when we are a complete mess and miss the person even more than we thought we could – and we may feel like all of our progress to this point has been for naught.

It’s important to remember, though, that on any journey, no matter the model we subscribe to, we stumble – and that’s especially likely on a journey like the one through grief that is never-ending. Whether we’re grieving or supporting someone who is, it is important to remember that we will stumble and struggle. These are not failures…they’re simply realities that happen. We may have moments of sadness, even though we feel as though we’ve moved far beyond that point – or we may have moments of joy when we feel as though it’s not appropriate. Never judge nor apologize for what you or someone else is feeling. That’s our subjective reality in the moment, and everyone is entitled to those feelings.

*****

About the author: Chad Harris is a graduate student at Hood College in Maryland, where he is pursuing a master’s degree in thanatology, as well as coursework in gerontology. He also holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Central Arkansas, as well as a master’s degree in social work from Case Western Reserve University. He is currently researching the role of mass media in shaping people’s perceptions of death and the impact of media coverage on grief and mourning, with the hopes of helping promote more responsible coverage of tragic events.