Death

10 Reasons I’ve Stayed in the Funeral Business

I’m coming up on 10 years licensed, a significant milestone considering that my embalming professor told me that 70% of funeral students never make it to the decade mark. To be honest, I never thought I’d make it this far. After I graduated mortuary school, I told my dad, “I think I’ve only got about 10 years for this business.” At the time, the constant barrage of death and dying, the night calls that I was always running and the dynamics of death culture had me doubting my resiliency. I also had aspirations of becoming an academic (something I’m still pursuing because I’m a nerd). But, here I am 10 years later, more committed than ever to the funeral business, so I thought I’d list 10 reasons why I’ve been able to stay. These reasons aren’t a catch-all for every funeral director, but they’re reasons why I’m still here.

Service.

Admittedly, I don’t wear a smile when my cell phone rings at 2 AM in the morning for a death call. Although I’m eventually kind, courteous and congenial when I go on the midnight call, even after 10 years those midnight death calls still wear on my like a weight. The chaos of death isn’t a healthy lifestyle with its unscheduled hours, its highly emotive culture and the demands that come with it. I think most funeral directors will agree that this business is not easy. But something happens to me when I see the family of the deceased. One minute I’ll be tired, unhappy and beaten, and the next minute I’m full of compassion, energy, and resiliency. There’s still something wonderful about the service aspect of this industry that keeps me here, that sustains me during the tough hours.

Our Associates.

Ten years ago I didn’t have enough appreciation for the people we rub elbows with. Death has a way of drawing out the beauty in humanity, which is why funeral directors are privy to some of the most beautiful people in the world. Whether it be the hospice nurses who give so unselfishly, the flower shops who help us out at the last minute, the sextons that waive fees for infants, the pastors who work tirelessly to help families, and any angel who has ever given us free coffee. If I ever left the funeral business, I’d miss crossing paths with so many wonderful people.

Humor.

From tweets about tying shoestrings in preparation for the Zombie Apocolypse, to finding the lighter moments at funerals, I’ve managed to make a distinction between serious and solemn. Death is a serious matter, but it doesn’t have to be solemn. That permission to laugh and lighten the mood has been a key part of my resiliency in this business.

No

If there’s one word that is utter sacrilege in a smaller funeral home like ours, it’s this tiny two-letter word. We simply don’t use it. I mean, when can we ever say “no” to a family that just lost their loved one?

But if we’re to survive, we have to introduce it into our professional vocabulary. Death has a way of being more demanding than life, especially the personal life of a funeral director. Death constantly clears our personal schedule books. We’re supposed to go to our son’s baseball game, but there’s an evening viewing. We’re supposed to have Christmas dinner, but there’s a death call. We’re supposed to go on a date, but there’s a family that wants to come in and make arrangements in the evening.

We have to find a way to allow ourselves to live our own lives in the midst of death. Sometimes that means hiring others to do some of our work, and sometimes that means creating better organizational systems and sometimes it simply means saying “no.” If I hadn’t learned to say “no”, I would have burnt out of this business years ago.

Affirmation.

Being told, “You’ve made this so much easier for us.” or, “Mom hasn’t looked this beautiful since she first battled cancer”, or “You guys are like family to us” means a lot to me. It’s important to know that what you’re doing is meaningful for the person you’re doing it for.

That verbal affirmation is huge in sustaining those of us in the dismal trade.

The Calling

I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t like the term “calling”. I’ll also be the first to admit that I never felt called to this business.

Callings aren’t predetermined nor are they divinely ordained. Neither are they mystical or set in stone. They’re not our “dream jobs” that can only be obtained with supreme talent, intelligence and luck.

A calling is when we hear the voices of those needing our help. Callings can arise in the darkest jobs, in the most monotonous of tasks and at the “lowest” positions. Callings are something we learn to love. Callings are something we choose to do because we develop an ear to hear and an eye to see. A person who is “called” is a person who has seen a need and answered so many times that it becomes a part of who they are.

Now, more than a decade in, I’m staying in this business because this call is something I now answer so naturally that it’s become a part of who I am.

$$$

When I was younger, I thought money didn’t matter. I’m older now. Consistent paychecks are good.

The Stories.

I love hearing tales of death and dying. Call me morbid, but I just find so much wonder, sacredness, spirituality and beauty in death stories. The stories are my ballast.

Empathy Vs. Sympathy

There’s a saying in the funeral business that goes something like this, “treat every family as though they were your own family.” That’s a nice sentiment, but it is not entirely practical.

There are times (at funerals especially) when all we can give is sympathy. When it’s outside of our ability to fully empathize with a person’s situation. After all, the person laying in the casket isn’t my father. This isn’t my daughter. This isn’t my family.

And that’s our job. You pay us to be directors. And we couldn’t handle much more. We have to maintain a certain level of objectivity because there’s only so much pain, grief, and heartache we can share until we too start to crash … burn out.

But, there are other times when you can’t help but be drawn into the narrative so that you enter the narrative and become a character in the story. Not just a director, but an actual character in the drama of life and death.

Sometimes all I can do is sympathize. Other times, I empathize. Allowing myself the permission to do both has been key.

Self-Care

I’ve been close to being burnt out. Landed in the hospital. Reevaluated life. I started to seeing a psychologist. I started anti-depressants. I started writing more. I started going to the gym more. Saying “no” more often. I started to realize that if I wanted to take care of others, I had to take care of myself. Self-care is the unselfish act of selfishness and I know for a fact that I’d be out of this business if I didn’t practice it.

The Worst Kind of Suicide Shaming

Photo credit: wonker. License: Creative Commons Attribution License

We had a funeral last week for an elderly man who died under hospice care. The family requested that the hospice’s chaplain, Chaplain Gerry, make a visit to their dying loved one. Gerry stopped around a couple times and made such a positive impression on the now deceased and the family that they asked him to conduct the funeral service.

After the service was done, the chaplain rode me with me in the lead car in the funeral procession, which led to some pretty serious conversations about his job on our way to the cemetery for the interment service.

Hospice chaplains have a unique combination of training in both spirituality and bereavement care, a necessary combination to be sure. I graduated from seminary and I know too well that seminary training severely lacks in bereavement training. Seminary students come out of school with their heads filled to the brim with so much God knowledge that they are nearly incapable of sitting in the human silence of death.

But not hospice chaplains. These women and men know how to tame their seminary training, they know how to sit in silence, listen and their view of God is rarely one that leads to such horrible sayings as, “It was God’s will” or “God never makes mistakes.”

I was talking to the chaplain about bad platitudes people use around death and he quickly got very mad as he recalled something from very early on in his career.

“Caleb,” he said. “I remember the worst thing I’ve ever heard.”

“At the time, I was a new chaplain at Caln Hospital and I was also a new pastor of a small, local church. A lot going on all at once. Which is often what happens when you’re fresh out of seminary as a new pastor.”

“I got a phone call late one night and it was a member of our church calling me. She was just hysterical.”

“I was trying to get her to calm down so I could understand what she was saying. And finally, she caught her breath and she told me her son had just shot himself in the attic. He shot himself in the head. Dead.”

He continued, “I’d seen a number of suicides and suicide attempts at Caln Hospital, but I knew this boy.”

“About 10 minutes before the service started, the boy’s mother came to me crying. She said, ‘Gerry, I’ve been doing so good during the viewing and visitation’. Gerry specified that it was a huge viewing, full of “on-lookers” as he called them. “But,” she said, “someone just came up to me and told me that she’ll be praying for me because she can’t imagine what it must feel like to know he not only killed himself but now he’s in hell.”

“Is that true?” she pleaded with Gerry. “Is my boy really in hell?”

Gerry stopped telling the story momentarily to let it all sink in. “I gave her a huge hug, and I told her as confidently as I could, ‘He’s not in hell.’ But I was so pissed.”

I started to get angry too. So angry that I momentarily lost perspective as to what I was doing. When I get in these intense conversations with pastors while driving the lead car, sometimes I forget that I’m leading a line of 30 plus cars through the winding farm roads of Chester County. My anger translated to a heavy foot and before I knew it I had to slow down to let the hearse catch up.

I chimed in wanting to share my two cents. I have personally experienced suicidal ideation. And I knew that suicide usually happens when our pain trumps our hope. It happens when we feel like we’re causing more harm in the world than good. I suppose that there are some people who selfishly use suicide as vengeance, but for most people, it’s about pain. It’s about having one’s mind so clouded by pain, or sickness or mental illness that we feel like the best we can give the world is our absence from it.

Surely, I told Gerry, hell is the last place a loving God would send such a hurting person.

“The worst part is,” Gerry concluded, “is that all these years laters, that mother still calls me, asking me for reassurance. To this day, she can’t shake those words.”

An Explanation as to Why Those Caskets Are Floating in the Louisiana Flood

You’ve probably seen those utterly disturbing pictures of caskets floating downstream from the Louisiana Flood.

It’s horrible. The stuff of nightmares.

You probably have some questions:

Why do they float?

Can those bodies be easily identified?

Shouldn’t the vaults keep them contained in the ground?

To the first question.

There are a couple of kinds of caskets. There are wood and metal caskets. Within the metals, there are sealing caskets (also known as gasketed or protective) and non-sealing caskets. Sealing caskets have a rubber gasket that creates an airtight seal when the sliding lock bar is cranked shut with the casket key. You may have seen funeral directors use said key after the lid is closed at a funeral. We insert it into a small crank hole at the foot end of the casket and turn it until the lock bar is totally tight.

Sealing caskets are the only ones that will float. Even though you would think a wood casket would float, because wood caskets don’t seal, they’re more likely to fill up with water and stay put in their vault.

Can those caskets and the bodies contained in them be identified?

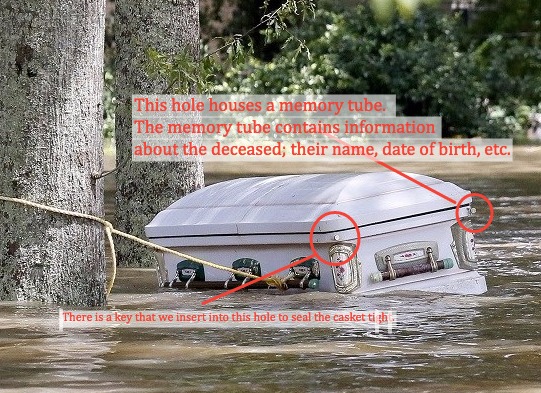

Most sealing caskets have what’s called a “memory tube.” You can see where that tube is located in the picture below.

If the funeral home filled out the memory tube, the process of identification is a whole lot easier. If the casket doesn’t have a memory tube, the process becomes much more complex. Although I’m not certain, I can imagine that DNA testing would be the last resort.

If the funeral home filled out the memory tube, the process of identification is a whole lot easier. If the casket doesn’t have a memory tube, the process becomes much more complex. Although I’m not certain, I can imagine that DNA testing would be the last resort.

Shouldn’t the vaults keep them contained in the ground?

Most cemeteries require vaults (a requirement that I disagree with, but that’s another blog post). Vaults, like caskets, can either be the sealing type or the non-sealing type. When the ground becomes over-saturated with water, the sealing vaults can pop out of the ground, causing the vault and the casket it contains to float away (see the picture below).

More often than not, it’s just the casket that floats away. In the case of the Louisiana Flooding, the vaults are exposed above ground (I would only assume it’s because there’s a high water table in these parts of the country). If the vault was buried underground as is the case in most cemeteries, it’s less likely that the caskets would pop out. But, since they’re that much closer to the top, it’s that much easier for them to stroll down the river when the flood waters come a rolling.

If you don’t want to go boating and floating after you’re dead, there are a few things you can do to make sure your body never washes away:

- Cremation

- Green burial

- Don’t use a sealing casket

- Tie your vault to an anchor.

Healed By Grief

The following guest post is written by Alise Chaffins:

A popular television show that ran during my formative years was Roseanne. It detailed the everyday life of a blue collar family trying to make it in the world. I watched the show, but it never fully resonated with me because I had a hard time believing that one family could encounter one bad experience after another. Surely at some point they would catch a break? It just felt a little unrealistic to me, watching with all of the wisdom of a high school student. No one has that many bad things happen to them.

For a long time, that was true. My life moved along with the kinds of ups and downs that you expect from life. Not free from pain, but certainly not categorized by pain.

Then from 2013-2014, everything in my life fell apart. My mom was diagnosed with ALS and passed away just 11 months later. I had an affair which ended my 16 year marriage. I got pregnant before my divorce was even final, and then suffered a stillbirth at almost 36 weeks of pregnancy. My oldest child came out as transgender and because we supported him, we were asked to leave our church.

Every time I felt like things were beginning to turn around, every time I felt like I was getting a handle on my life, something else would cause me to lose my grip. By August of 2014, I felt like I was drowning in grief.

I tried to ignore it. I tried to fight it, but as I did, the more that I discovered that I was consumed by it. There was no escaping grief, it went with me no matter where I was. Fighting might leave me with a temporary reprieve, but more often than not, it simply left me more exhausted than I already was.

Rather than ignoring or fighting, I began to realize that I had to be willing to experience my grief more fully in order to move through it. I had to find the places where hurt threatened to choke me and dig into them. Instead of looking to be healed from grief, I began to look for ways to be healed by grief.

As I opened up about my grief, I found that there were others who would join me in that sacred space. Not looking to fix me, just those who wanted to sit with me, to comfort me in my sadness. People who would listen to what I was saying, and to what I didn’t say. People who offered practical help when I asked, and even when I couldn’t ask.

I found that when I pulled my grief in close, it had less power over me. I felt less guilt about mourning various losses because I recognized that grief was not my enemy. I experienced less shame as I realized that I had a right to grieve losses, even if they were gains for others. By becoming more open about bereavement and leaning into grief, I was able to find hope, both from outside sources and from within me.

We will all experience loss at some point in our lives. We can try to run from it. We can try to fight it. We can try to numb it. We can try to heal from it.

Or we can embrace it. And we can be healed by it.

****

Her book Embracing Grief: Leaning Into Loss to Find Life is now available.

Miscarriage and the Confusion of Sinful Grief: A Response

© 2007 Melissa Doroquez, Flickr | CC-BY-SA | via Wylio

I stumbled upon an article entitled Miscarriage and the Confusion of Sinful Grief that was posted at the Reformed Christian website “The Gospel Coalition”.

Jamie Carlson (who recently miscarried) wrote the post as a reflection on sin and grief. Here’s a quick except from her post:

After my miscarriage, it hit me—grieving and sinning go together. Perhaps the most confusing and ongoing part of miscarriage recovery was fighting temptation and rooting out the sins laid bare by suffering. Grief came as expected, but the intensity of emotions made it so difficult to distinguish temptation and sin from grief that I was paralyzed—unable to move forward toward healing.

Jamie continues by stating that soon after she miscarried, a number of her friends started announcing their pregnancies. She classifies her reactions of jealousy, annoyance, anger and minimization to such announcements as “sin”, as something inherently wrong.

Part of me is sensitive to Jamie’s situation. My wife and I often experienced similar feelings of jealousy after we came to the realization that we were infertile. It was hard to share in another person’s pregnancy announcement when we knew we could never conceive.

And while I respect Jamie and her attempt to overcome her feelings of jealousy and anger towards other expecting mothers, I think it should be made absolutely clear that grief is NEVER inherently wrong.

As much as I disagree with Jamie’s basic idea that “sinning and grieving” go together, we should understand that we DO stupid things when we grieve. And there ARE healthy ways to grieve and unhealthy ways to grieve. Not every response to grief is good. Not every way of handling grief is healthy.

But the conversation becomes really convoluted when we shift our talk about grieving from “healthy grief vs. unhealthy grief” to Jamie’s language that points to “holy grief vs. sinful grief.”

Healthy grief is always messy, disorganized, and full of new, raw emotions. Healing a wound involves blood, scabs, stitches, bandages and other less desirable devices. Same with healing from grief (although I’m not sure we ever really heal from grief). There are healthy ways of healing a wound and there’s unhealthy ways. To think, though, that those unhealthy ways are sinful only adds another burden to the already burdened soul of the bereaved.

Associating grief with sin encourages our strong tendency for people to hid their grief. It’s culturally normal for us to repress our thoughts, our tears, our emotions to the detriment of our healing. Imagine how much more we’d repress our thoughts, our tears, our emotions if we thought such things were boarding sinful?

Grief must be shared. It must be talked about. And it should never be hidden like it’s some ugly sin.

I hope Jamie finds healing. And I hope she finds friends who let her share her very normal, very human and very messy grief.