Death

An open letter to Heroin from a funeral director

Photograph Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/raschau/

Title: Fuck Heroin

Fuck Heroin. FUCK. IT.

That’s what I want to say when I get a phone call from a crying son, daughter, husband, wife, girlfriend, or boyfriend telling me their loved one has died from an overdose. But I don’t say that. I don’t say it because it’s impolite and I’m supposed to be the even minded professional to your grief clouded bereavement.

But, “I’m sorry for your loss” and “my deepest condolences” just don’t work when a 19-year-old daughter was found in the basement of her friend’s house after two stints in rehab and five months clean. This was supposed to be the beginning of her life, not the horrible end.

Or, what do I say to the sixteen-year-old son who wants me to call him as soon as I get his mom to the funeral home because “that will be the first time in my life that I’ll know exactly where she’s at”.

Or, what do I say to the 30-year-old wife with three kids and no income, little support and now she has no husband.

Fuck it. FUCK HEROIN. That’s what I want to say.

How about the parents who tell me, “I’m glad it’s over. I haven’t slept in years, but last night I actually slept because I knew he wasn’t out hurting himself or someone else.”

Or the parents who tell me with blank expressions that they had absolutely no idea their daughter was using. That she was excelling in college, holding a steady relationship with her boyfriend, working part-time and now she’s on our morgue table.

What do I say to the young husband who tells me, “We don’t have any money for a funeral, she blew our savings and her life on this relapse.”

How do I respond when that very same young husband follows it up with, “how do I explain this to my kids?”

And then there are the times when the body has been left somewhere, abandoned by so called friends, and it’s starting to decompose. “Can I just see my dad one more time?” the young man asks. “Yes, you can,” I say, “but this doesn’t look like the man you expect to see.” The son replies, “That’s fine. I haven’t seen him in five years so I don’t have any expectations.”

FUCK HEROIN. I’m getting tired of these stories. I’m tired of unstitching and embalming autopsied bodies that are discolored and broken down by addiction. I’m tired of hearing the empty cries of “My, baby, my baby! How did this happen?” How did we get here?” when the mother sees her son in a casket. I’m tired of children asking, “what happened to mommy?” and “when will she wake up?” at funerals.

I’m getting tired of these stories. I know addiction is a disease. I understand that shame is never the path to healing. There’s no shame here towards the addict. The enemy is very clear. We can all agree that this particular disease, this particular addiction is worthy of our most harsh, most striking, most caustic curse words we can find.

For all the fatherless and motherless children I’ve served …

For all the widows and widowers I’ve walked with through the valley …

For all the bereaved parents now childless …

For all the individual lives you’ve stolen, all the futures you’ve killed, and all the love you’ve grieved …

I raise my middle finger to you, heroin.

Fuck you.

via GIPHY

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

10 Pieces of Advice for New Funeral Directors

One. Nobody who “wants” to be a funeral director will make it.

It isn’t something you want in the way that you want a boy/girlfriend or a new car. No. It’s more like marriage. It’s a commitment that’s intended to last. It’s not a job … nor is it just a profession … this business is a lifestyle. And if you’re not ready to marry it, then move to another job that demands a less committed relationship.

Two. Dress Above Your Station

I’m always impressed by a funeral director who dresses well. Find a good tailor, buy good shoes, spend extra on that suit that fits you really well, keep your hair in shape and smell good. It might cost you money that you don’t have, but it will pay you back in confidence and numerous good-humored flirtatious advances from people three times your age.

Three. In the words of Aaron Burr, “Smile more. Talk less.”

What made Hamilton cool is that he didn’t care about his image, he cared about his legacy. Burr was the antagonist only because he cared about his image and never forfeited that image for something lasting. But Burr’s adage of “Smile more. Talk less.” isn’t all bad per se. It may have been bad for Hamilton, but for those of us in the funeral industry, it’s pretty good advice.

Four. Don’t try to be a perfect professional

One of the common pitfalls I see in young funeral professionals is that they’re entirely too stressed out in their pursuit to be the perfect funeral professional. Families don’t want you to be stressed out. They don’t need a perfect funeral director. They need you to be calm, in control of your stress and ready to be present. It’s hard, I know because I was once that stressed out “professional”, but somewhere along the way I stopped trying to be a consummate “professional” and it was then, and only then, that I really started being present and helping families.

This also means that you know your knowledge boundaries. Direct those questions outside our professional knowledge to the people who are qualified to answer. We aren’t lawyers, doctors, grief counselors or theologians. And when we don’t know an answer to a funeral question, ask a mentor. It’s okay if you don’t know an answer; what’s wrong is when we let our pride get the better of us and we act like we do.

Five. You will get used to the schedule

When you first start in this business, ITS SOOOOOO DAMNNNN TOUGHHHHHHHHH!!!!! The holidays. The weekends. It even takes our nights! And after it takes our weekends, and our sleep, it tells us to get back up at 7 AM because there are two funerals we have to work the very next day. It really does take awhile for our bodies and minds to get used to the schedule. Sometimes our bodies and minds need help getting used to the schedule. Sometimes we might need a psychologist. Sometimes we might need a fitness instructor. But most times we just need a good nap. If you stick to it, you’ll eventually be able to keep up.

Six. Allow yourself to learn patience

Have you ever been around grieving people? At times grieving people act like they’re out of their minds. And, there’s times when grieving people can act … well … they act kinda crazy. And it’s their right. In fact, it’s the reason WE exist. Their world has been pulled out from under them, they haven’t a foot to stand on and everything that they used to know is suddenly … gone. And you’re here to help create semblance in the crazy.

It can be tough to learn patience, especially when we’re working on small amounts of sleep and are arranging multiple funerals at once. But it’s something we have to do.

Seven. Continually remind yourself why you’re here

The secret to learning patience, to getting used to the schedule, to finding resilience during the tough schedule is this: Learn to love serving others. Probably the best means to cope with the funeral business is found in the people we serve. Love them intentionally and don’t be afraid to find joy in meeting their needs. Don’t be afraid to hear their stories and become part of their family.

Eight. It takes a while to grow into this business (in other words, have patience with yourself)

Generally, you work with older people and older people prefer to work with people within their generation. It can be hard for a younger person to establish themselves in this business, but it’s very possible. There are no Mark Zuckerburg 18-year-old prodigies in funeral service because being a funeral director is about life experience, not business acumen.

Nine. Find a Mentor

This doesn’t have to be anything official. You don’t have to update your Facebook status to “in a mentor relationship with ….” Find someone you respect in this profession, someone who has more experience than you do, someone who is willing to answer your numerous question and stick close to that person (it’s best if you work with that person). At one time, this industry was a trade; in other words, it wasn’t taught in schools and regulated by state boards. It was a trade that was taught by a mentor to an apprentice and the skills and business acumen were passed down through word, practice and in house training. I do believe that the best funeral directors are still being produced when they treat this work like a trade. They find a mentor, and they learn by the guidance of someone older and wiser.

Ten. Learn to practice self-care

I’ve been close to being burnt out. Landed in the hospital. Reevaluated life. I started to see a psychologist. I started anti-depressants. I started writing more. I started going to the gym more. Saying “no” more often. I started to realize that if I wanted to take care of others, I had to take care of myself. Self-care is the unselfish act of selfishness and I know for a fact that I’d be out of this business if I didn’t practice it.

If you’re a new funeral director (or you want to be one), I do believe you’ll gain a lot of perspective from my book. It’s a transparent and personal look at the rigors of being a funeral director.

10 Simple Ways to Avoid Being an Asshole around Death

One. Don’t use a death as an object lesson

The first piece I ever wrote for a magazine was about the death of Jackass crew member Ryan Dunn and how people were using his reckless driving death as an object lesson.

Even though it’s tough to do, especially when we want to teach our kids a lesson about “why drugs are bad” and “why you shouldn’t drink and drive”, turning a life into an object lesson grades against the heart of what it means to be human. People aren’t objects. And death isn’t a lesson. Death is this cauldron of feelings, loss, void, laughter, fear, … it’s everything that is human. Let’s keep it that way.

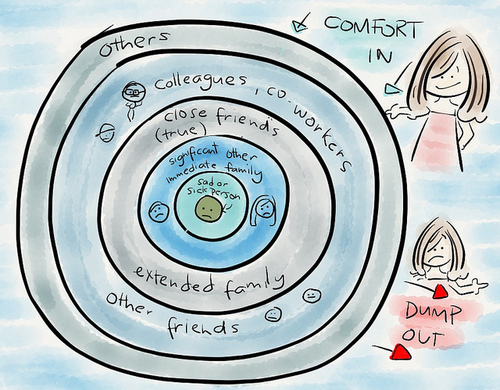

Two. Remember the Circles of Grief

The circles of grief (AKA the Ring Theory) is this: Imagine concentric circles (see photo above). The smallest ring in the center is the person closest to the deceased, whether that person is the deceased’s spouse, a parent, a child or all of the above. The next circle is representative of the immediate family and very close friends. A third ring could be extended family, close co-workers, etc. A fourth ring might be schoolmates, or church acquaintances, etc. The rings keep going.

The idea with the circles of grief is that comfort always goes in, and dumping always goes out. If you’re a secondary relationship, it’s not your right to dump all of your grief on the spouse of the deceased. If you’re a fourth ring relationship, you should NOT expect a close friend to comfort you. If you’re the closest to the deceased, it’s okay if you dump outward. And if you’re an outer ring, you should expect to comfort the inner rings. These circles act as a great template for any of us who are ever in a position to comfort the bereaved. If you act otherwise, you’re probably being an asshole.

Three. Avoid cliches

When people use comfort cliches like “you’ll see him again someday” or “things will get better”, they are often more concerned with comforting themselves than comforting the bereaved. Comfort cliches are the practical outpouring of death denial. Cliches are band-aids that people try to put on a massive wound. These band-aids oversimplify the problem, they minimalize grief and they trivialize the death. If you don’t want to be an asshole around death, avoid them at all cost.

Four. Don’t Join Westboro Baptist Church

Just saying.

Five. Don’t Say or Write Negative Things about the Deceased

This is simply death etiquette. It doesn’t matter if the deceased was the worst bastard you’ve ever known, it’s never cool or respectable to take a shot at someone when they can’t defend themselves. And nobody is more “unarmed” than when they’re dead.

Six. Don’t Fill Silence with Words

“The real art of conversation is not only to say the right thing at the right place but to leave unsaid the wrong thing at the tempting moment.” —

Dorothy Nevill

When you’re around grief, sometimes you speak too soon, so you decide to wait in silence. Your friend starts to cry. You respond to her tears with your own. Even though you want to respond with words, you know this isn’t the time for words. There are no perfect words here. There’s no perfect anything here. And so you wait.

You stay. Listen. Silence. You take her pain into your soul. Hours pass.

You’ve spoken, not with words or advice; not by trying to solve the problem; nor by placing a limit on your time. You’ve taken the uncomfortable silence, allow the grace for tears, for brokenness; you’ve allowed yourself to sit in the unrest without trying to fix it.

Seven. Don’t Make the Funeral about You

This past Saturday night, I stood there behind the register book, striking up a conversation with people as they enter the sanctuary. The viewing line snakes around the church, down the hall, and into the basement as we try to extend it through the corridors of the church so as to keep the line from going out into the hot and humid weather of a Pennsylvania summer. The family of the deceased is taking their time, talking to each and every person who has come out on this sweaty night.

“Other funeral directors stand by the family’s receiving line and tell them to keep their conversations short and simple”, one person stated.

“We don’t do that”, I said politely.

Another couple comes through the line and complains that they’ve been standing in line for half-an-hour AND by the look of things, they’ll probably be in line for another half-an-hour. “Can’t you do anything?” they beg.

After having this conversation about 10 times over the next hour, I’m getting tired of my joke and I’m getting tired of people complaining.

I want to pull them close to my face and whisper, “This isn’t about you.”

Perhaps the greatest loss that comes with the drone of our busy lives is that in losing silence, we’ve lost patience, and in losing patience we’ve become so inherently selfish that when we go to a funeral we forget that it’s not about us. Too many of us have become funeral assholes.

Eight. Don’t Use Death to Evangelize

Our funeral home’s website has online obituaries for those we are serving. When someone goes to an obituary on our website, they can write out condolences and post it for the family of the deceased. A couple years ago we had to ban about five users who went to every one of the obituaries and left a “condolences” that said something like this: “Although we don’t know you, we are sorry for your loss. Use this time to contemplate your salvation and your relationship with Jesus.” These “condolence evangelists” may have been well-intentioned, but they totally missed the point.

The point is to remember the deceased and be near to those who loved and lost. The point isn’t to “get people to heaven” but to bring heaven down through love, community and lots of really good comfort food.

Nine. Be Culturally Sensitive

We all know that when somebody dies, bacon is by far the best dish to bring the grieving family … unless that family is Jewish or Muslim. We also know that cremation is a viable option, but let’s not preach about the sins of embalming and the environmental impact of a full burial to an Eastern Orthodox family. Don’t be THAT asshole.

Ten. Avoid Grief Timelines

Validate, validate, validate. It’s okay if somebody is grieving years after they lost their spouse. It’s okay if their grief expressions look different than yours. Sure, some grief might need the help of professionals, but that doesn’t mean the grief is wrong or sick. And because we validate, we never, never, never say, “Well, you should be over this by now!” or “you’ve been grieving for two years now, it’s time to move on.” There is no timeline for grief, but there is no timeline for love. We let love express itself and we validate that expression (unless that expression is cutting off the heads of cats and using those heads to make a mosaic of the deceased’s face. At that point you call Dr. Phil.)

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

10 Subculture Funerals that Would Be Really Cool

One. Nudist Funeral.

From an embalming perspective, laying out a nude nudist for a viewing would be difficult. Displaying a naked body for a viewing would mean that I’d have to hide all my sutures through some expert waxwork, and I’d have to make sure the embalming fluid was evenly distributed to stave off any odd discoloration. Generally, if an embalmer gets good distribution and an even color in the head and the hands, we’re good, because the head and the hands are the only parts of the skin visible for the viewing. Even in a thoroughly embalmed body, there might be some discoloration in the feet, or other parts of the body. But, it’d be a fun challenge and would demand that I’d do some of my best work.

Two. Trekkie Funeral

“Beam me six feet down, Scotty”

Three. A Furry Funeral

This would be the exact opposite of a nudist funeral because no skin would be showing if the deceased wanted to be embalmed. If the disposition was cremation, we’d get one of those Teddy Bear Urns.

Four. Cosplay Funeral

So many ideas! If the deceased wanted to be Wonder Woman, that whole even distribution thing would come into play. If the deceased wanted to be dressed as Nintendo’s Mario, it’d be easier. The casket could even be made to look like a Mario Cart. If I was working the funeral, I’d probably dress up as Gomez Addams or a suit-clad Dracula (“I vant to drain your blood!”).

Author: Fernando Branquinho

Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/aki_jazz/

Five. A Drag Funeral

I’d totally dress in drag for the funeral, but I’d probably go for a David Bowie gender blending look to maintain a level of distinction. Dressing a deceased person in drag would be beyond my capability. I’d find a friend of the deceased in the drag world to help with the dressing and makeup, but Lord knows I probably don’t have enough makeup in the prep room to pull it off.

Six. Juggalo Funeral

Nope. Wouldn’t do this one.

Seven. Steampunk Funeral

This would be so fun. The things you could do to a casket to make it steampunk. I’m getting excited just thinking about it. You could make a really elaborate locking system with a weighted lid so that you’d click a button and the lid would lower and lock in place. Click it again, and the lid would rise on its own. But, if you’d make something this awesome, it’d be really hard to bury it beneath the ground.

Of course, this steam powered hearse would be an absolute must.

Eight. Neo-Victorian Funeral

This would be boon for me because the Victorians were known for their absolutely lavish funerals. Sell alllll the copper caskets! Do you want two Prometheans? How about a vault made out of gold?

Nine. Bro Funeral

I’d mix a little “extra tan” dye in the embalming fluid to give the bro that sun-kissed look. I’d have the image of Ryan Lochte painted on the casket lid. The deceased would be dressed in Southern Tide flannel shirts, and John Mayer would be playing during the viewing. Once the bro slice would be buried, all his bros would pour beer on his grave while chanting his fraternity motto.

Ten. Bodybuilding Funeral

ADD SOME PROTEIN POWDER IN THE EMBALMING FLUID! Turn up the pressure on the embalming machine and get those arteries and veins distended. Turn on the workout music for the viewing. We’d only need one pallbearer who could deadlift the casket and snatch walk it all the way to the hearse. But really, who needs a hearse when you have men who could throw

If you like my writing, you might like my book: