Grief

Grief Shaming: Why some people believe your grief over Robin Williams is misguided

My social media feeds have been spattered with statuses such as this:

“People need to wake up! He was JUST a celebrity!”

Or this:

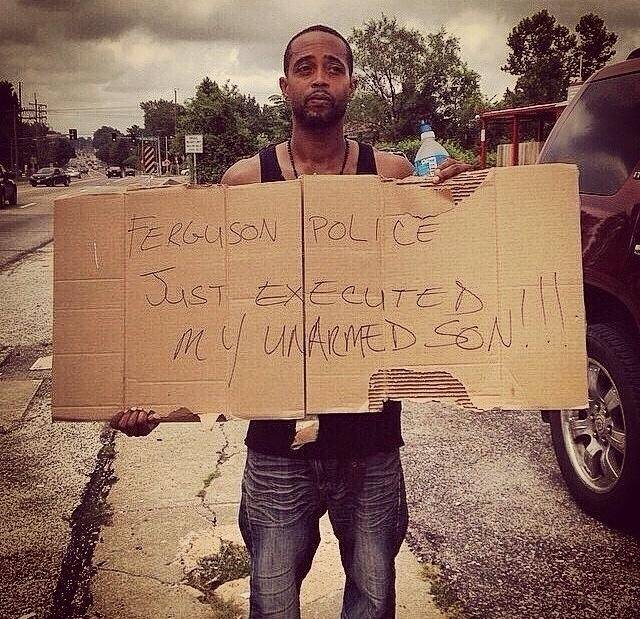

“Why are so many people grieving over Robin Williams when Mike Brown was shot and killed for NO REASON!!!”

And then there’s the complaint that we forget crimes against humanity, like those atrocities being committed by ISIS against the innocent:

“The media covers celebrity deaths, but they totally forget that ISIS is slaughtering children.”

And I admit, I’m guilty of the same type of grief shaming and grief measuring. There’s been a few times when I’ve walked into a nursing home, hospital or home to see the grandchildren and children weeping over the body of a 90+ year old deceased person. And I want to say, “You know last week I buried a 15 year old boy who was struck by a car … that family has a right to grieve, but this person that you’re crying over … this person has lived 90 full years of life.”

Or, something like this: “Most people never get to see their parents live into their 90s. You should be celebrating that fact that you shared so much time with your loved one. STAAAAPH CRYING!!!”

And, from a level of objectivity, I (we) are right.

I mean, have you read about the recent Mike Brown tragedy? An eighteen year old unarmed black male gunned down by a white cop in Ferguson, Missouri.

And the ISIS stories are so horrific that it’s difficult to recount. ISIS is slaughtering children. And turning other children into monsters.

ALL THIS IS GOING ON IN THE WORLD AND YOU’RE MOURNING THE DEATH OF A COMEDIAN??? A COMEDIAN WHO COMMITTED SUICIDE???

The problem with grief shaming and grief measuring is this: there isn’t objectivity.

See, grief is proportional to love and intimacy. The more you love someone and the closer you are to them, the more you grieve. And telling someone that their grief is misguided is as wrong as telling someone their love is misguided.

Sure, the death of a 90 year old isn’t as tragic as the death of a 15 year old, but that doesn’t make the grief for the 90 year old any less real or any less valid. You grieve because you love and we all love differently. We love different people. We love those people in different ways. And our attachments are as varied as we are unique. I’ve learned the grief NEVER deserves judgment, but it ALWAYS deserves compassion.

My friend Tracy, who has an incredible way with her words, wrote this:

I saw a thing today complaining about the focus on Robin Williams’ death instead of the horrible atrocities in Iraq and around the world. Can I tell you something? Mr. Williams’ death HAS affected me more deeply. Even if that makes me a bad person.

I think it’s because I understand something about depression and have no concept of being a refugee. I think it’s because I’ve considered suicide at one point in my life but I’ve never needed to climb into a rescue helicopter to escape genocide. I think it’s because I’ve been touched more than once by mental illness and addiction in the lives of those around me but I’ve never had to see a neighbor child cut in half. I think it’s because I can’t do absolutely anything at all about Iraq or Sudan or DRC, but I can look in the eyes of the people around me and make sure they are actually ok and not just pretending. Step up to my own war against profound and crushing grief and sadness. Do something small to release the stigma of mental illness in my own corner of the world.

I’m not one to really care much about celebrities and their divorces/affairs/babies/

movies/whatever, but this one hits me. And instead of lashing out at those who mourn a suicide by calling their attention to “more important” deaths, maybe we need to check in with the people who are mourning Mr. Williams and make sure they’re ok. (I’m ok, really. Thanks.)

Many of us grew up with Robin Williams.

He was the Genie in Aladdin that made us laugh.

He made us believe in the magic of Neverland.

Williams sparked our imagination in ‘Jumanji’.

He somehow softened the blow of divorce in Mrs. Doubtfire

And now, he’s making many of us reconsider our understanding of depression and suicide.

Instead of shaming and measuring other people’s grief, isn’t it more helpful if we open up a space in our hearts for compassion and empathy? And maybe, if we show others empathy for their grief, they will in turn show empathy for ours.

The key to solving problems like ISIS and the injustice of the Mike Brown tragedy doesn’t start with shame and judgment. The key to solving problems big and small starts with showing compassion. It is love, after all, and not judgment, that covers a multitude of sins.

“Real” Men and Mourning

I’m a big fan of the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles. I read their website every day, watch all their games and follow the off-season stories.

Exactly two years ago the Eagles’ former Head Coach (current Head Coach of the Kansas City Chiefs), Andy Reid, lost his 29 year old son Garrett to a battle with drug addiction. Garrett died on a Monday. Garrett’s funeral was the following Tuesday. And Andy Reid — Garrett’s father — was back to coaching the Eagles THE DAY AFTER the funeral for their first preseason game.

I don’t comment on a person’s grief work, so if Andy Reid thinks that going to his job the day after his son’s funeral is the right thing for him and his family, then so be it.

Men will often attempt to use work as a way to process their grief. We will also attempt to care for others as a means to process our grief and may neglect our own needs for the sake of one’s family, or — in Andy’s case — his team. So, as I said, I’m not judging Andy’s grief work.

But I do want to comment on HOW Reid’s quick return to work is being interpreted by his players.

Jason Kelce, the Eagles starting center, had this to say some two years ago:

“I think this is just Andy. We’ve got guys who lose relatives all the time on the team, and they’re gone for a significant amount of time, and Andy’s talking about being back already. That just goes to show his level of professionalism — his level of manhood really. There’s no question it’s eating at him inside. To be able to not show it, to be able to hold it down just so the team doesn’t see him like that, that’s impressive.“

To be able to not show his grief over the tragic death of his son … to be able to hold it down so the team doesn’t see him “like that”, that’s impressive? What?

What is Kelce implying? Is he implying that Reid’s “level of manhood” would be in question if the team saw him grieve … if the team saw him cry? Is Kelce implying that manhood equals emotional repression? Yup, I think that’s what Kelce means. And Kelce is implying that showing one’s emotions IS NOT manly and would not be good for other men to see.

Seriously? Are our young boys still being taught this crap by their male role models?

Let me clear a few things up for Mr. Kelce.

1. While it may be true that men are generally less emotional, manhood is not increased (or decreased) by one’s ability to repress emotion.

2. You may want to be strong when a death occurs, but strength — like manhood — isn’t determined by one’s ability to repress emotion.

3. There is no “manly” way to grieve, so don’t let someone (especially another man) tell you how you should feel or shouldn’t feel.

4. Mourning IS manly IF it’s performed by a man.

5. If you show grief in front of other men, and they judge you or attempt to diminish your mourning, find other company so that you can work through your grief in a more healthy environment.

Whether by nature or nurture, men and emotions have a difficult relationship that is farther complicated by a highly complex and uncontrollable experience like death. The bottom line is this: there isn’t a RIGHT or WRONG way for men (or woman or children) to grieve and mourn. But, it is healthy if you can find a place, space and group that can allow you to work through your grief on your own pace. Ideally, look for a group of people who can walk with you through the valley, and if you find that place and those people who can allow you to work through your grief, you are on a healthy path.

If You’re Dealing with Complicated Grief, Seek First Your Therapist, Not Your Pastor

Ernest Becker proposes that depressed individuals (specifically those depressed from death) suffer both doubt in their faith and doubt their value within their worldview. In other words, grieving people often doubt their religion and the God of their religion.

Kenneth Doka suggests that “one of the most significant tasks in grief is to reconstruct faith or philosophical systems, now challenged by the loss” (Loss of the Assumptive World; 49). All forms of grief, normal, complicated and especially traumatic grief produce doubts about one’s faith.

If you’re dealing with grief, your entire worldview is probably being challenged. It’s only natural that we attempt to seek council in such times; but, it might not be your best choice to seek your church and pastor’s help.

As many of you know, I’ve battled depression this past year; and while grief and depression are different, there’s many similarities. As I’ve adjusted to life with depression, there’s a number of things that I’ve learned and this is one of them: Most churches and pastors (and religious friends) aren’t equipped to recognize and address the depressed. We should not expect them to be equipped. But we do. They haven’t been trained to understand the psychosomatic nature of depression; nor have they a background in tasks of mourning or grief work models; the different types of grief and how each one should be approached.

And it’s okay to recognize the limitations in our religious community.

Today’s church speaks the language of affirmation, the language of light (cataphatic theology as opposed apophatic theology) to such a degree that doubt and darkness can sometimes be viewed as sin.

Depression, for some religious communities, is sometimes seen as a curse of God.

And grief, per the theology of many religious communities, is something that God might not feel, so neither should we (at least for an extended period of time).

And while some churches can be understanding of grief, and the doubt and depression that comes with it, few are prepared to understand how said grief, doubt and depression affects you.

We can become more course, more rigid and more … unacceptable. And, honestly, it’s possible that we do indeed become unacceptable for many churches, as our darkness and our doubt takes us out of the comfort realm for many within the church.

Indeed, many pastors recognize the limits of their training and can recommend professionals to help with your grief, etc., but some don’t recognize their limits. They can provide first or second level assessment (i.e., “you need some professional guidance”), but the deeper levels of assessment and counsel should be left to those grief specialists.

Unless your church or pastor has a professional background in understanding depression and/or grief, I think we do both our pastors, our religious friends and ourselves a great service by seeing someone who is professionally trained.

Should We Medicate Grief?

Last year The American Psychiatric Association (APA) published their Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5); and it’s created no small stir among the psychiatrist community.

One of the main issues that psychiatrists are having with the DSM-5 is that it is lumping normal grief into Major Depressive Disorder. Here’s a quote from Dr. Allen Frances, professor emeritus of Duke’s School of Medicine:

(In the new DSM-5) Normal grief will become Major Depressive Disorder, thus medicalizing and trivializing our expectable and necessary emotional reactions to the loss of a loved one and substituting pills and superficial medical rituals for the deep consolations of family, friends, religion, and the resiliency that comes with time and the acceptance of the limitations of life.

*****

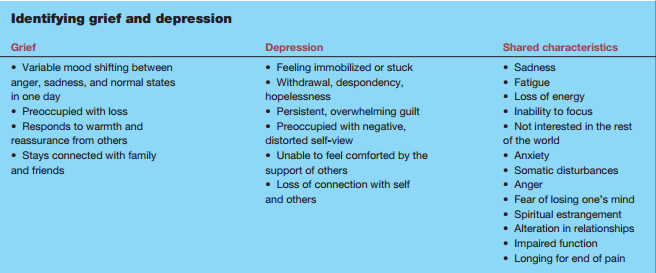

There are many shared characteristics between grief and depression, but there’s also some distinct differences. Dr. Ginette G. Ferszt states this:

Although everyone grieves differently, grief and depression share several common characteristics. Both may include intense sadness, fatigue, sleep and appetite disturbances, low energy, loss of pleasure, and difficulty concentrating. The key difference is that a grieving person usually stays connected to others, periodically experiences pleasure, and continues functioning as he rebuilds his life. With depression, a connection with others and the ability to experience even brief periods of pleasure are generally missing. Sometimes people describe feeling as if they have fallen into a black hole and fear they may never climb out. Overwhelming emotions interfere with the ability to cope with everyday stressors.

Here is a chart that shows the similarities and differences between depression and grief.

*****

Should we medicate grief?

Mostly “no”, but in some cases “yes”. Here is when grief may need some type of medication:

- If grief-related anxiety is so severe that it interferes with daily life, anti-anxiety medication may be helpful.

- If the person is experiencing sleep problems, short-term use of prescription sleep aids may be helpful.

- If symptoms last longer than two months after the loss and the diagnostic criteria are met, the person may be suffering from Major Depressive Disorder. In this case, antidepressants would be an appropriate therapy.

Here is are some criteria to determine if grief has transitioned to Major Depressive Disorder.

- Feelings of guilt not related to the loved one’s death

- Thoughts of death other than feelings he or she would be better off dead or should have died with the deceased person

- Morbid preoccupation with worthlessness

- Sluggishness or hesitant and confused speech

- Prolonged and marked difficulty in carrying out the activities of day-to-day living

- Hallucinations other than thinking he or she hears the voice of or sees the deceased person. (From Nancy Schimelpfening’s “Grief and Depression”).

Ultimately, grief is the response to loss. And no amount of medication is going to bring that loss back. We must learn to live with the loss of someone integral to our very being. If medication hurts that learning process, then it’s destructive. If it can help us learn to live in the “new normal”, then it becomes an aid to understanding life after loss.

I think the following quote sums up the core of why medicating grief is usually not healthy:

15 Things I Wish I’d Known About Grief

Today’s guest post is written by Teryn O’Brien:

After a year of grief, I’ve learned a lot. I’ve also made some mistakes along the way. Today, I jotted down 15 things I wish I’d known about grief when I started my own process.

I pass this onto anyone on the journey.

1. You will feel like the world has ended. I promise, it hasn’t. Life willgo on, slowly. A new normal will come, slowly.

2. No matter how bad a day feels, it is only a day. When you go to sleep crying, you will wake up to a new day.

3. Grief comes in waves. You might be okay one hour, not okay the next. Okay one day, not okay the next day. Okay one month, not okay the next. Learn to go with the flow of what your heart and mind are feeling.

4. It’s okay to cry. Do it often. But it’s okay to laugh, too. Don’t feel guilty for feeling positive emotions even when dealing with loss.

5. Take care of yourself, even if you don’t feel like it. Eat healthily. Work out. Do the things you love. Remember that you are still living.

6. Don’t shut people out. Don’t cut yourself off from relationships. You will hurt yourself and others.

7. No one will respond perfectly to your grief. People–even people you love–will let you down. Friends you thought would be there won’t be there, and people you hardly know will reach out. Be prepared to give others grace. Be prepared to work through hurt and forgiveness at others’ reactions.

8. God will be there for you perfectly. He will never, ever let you down. He will let you scream, cry, and question. Throw all your emotions at Him. He is near to the brokenhearted.

9. Take time to truly remember the person you lost. Write about him or her, go back to all your memories with them, truly soak in all the good times you had with that person. It will help.

10. Facing the grief is better than running. Don’t hide from the pain. If you do, it will fester and grow and consume you.

11. You will ask “Why?” more times than you thought possible, but you may never get an answer. What helps is asking, “How? How can I live life more fully to honor my loved one? How can I love better, how can I embrace others, how can I change and grow because of this?”

12. You will try to escape grief by getting busy, busy, busy. You will think that if you don’t think about it, it’ll just go away. This isn’t really true. Take time to process and heal.

13. Liquor, sex, drugs, hobbies, work, relationships, etc., will not take the pain away. If you are using anything to try and numb the pain, it will make things worse in the long run. Seek help if you’re dealing with the sorrow in unhealthy ways.

14. It’s okay to ask for help. It’s okay to need people. It’s okay, it’s okay, it’s okay.

15. Grief can be beautiful and deep and profound. Don’t be afraid of it. Walk alongside it. You may be surprised at what grief can teach you.

What are things you’ve learned about grief that you wish you’d known when your loss first happened?

*****

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Teryn O’Brien works in marketing with various religious imprints of Penguin Random House. She spends her free time roaming the mountains of Colorado, writing a series of novels, and combating sex trafficking. She’s of Irish descent, which is probably where she gets her warrior spirit of fighting for the broken, the hurting, the underdog. Read her blog, follow her on Twitter, or connect with her on Facebook.