Funeral Directing

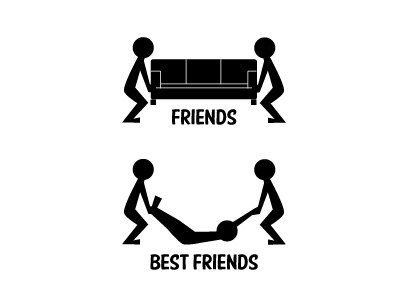

“Will You Help Me Pick Up a Body?”

This is a question I’ve had to ask a few of my friends ever once upon a busy day at the funeral home.

House removals are different than hospital and nursing home removals. “House calls” as we call them often involves obstacles (like stairs, furniture, dogs etc.) that one person cannot overcome alone.

While hospital and nursing home removals usually only require ONE person to make the removal, house calls require TWO (sometimes more depending on the place of death and the size of the deceased).

There’s three of us at the funeral home who are capable of making house removals. When one out of those three is on vacation, leaving two behind, things can get sticky. Every once upon a busy day when we are picking up more bodies than our personnel can handle, I’ll have to randomly call in some back up … which usually ends of being one of my buddies.

Last year I called two separate friends on two separate occasions.

When I called both of them, I gave them this line:

“Do you want to make $150 dollars for an hour’s worth of work?”

“Sure!”, they said.

And when I told them HOW that $150 was to be made, both were still willing. After telling them what to wear, how the whole procedure would work and what they should expect, they both did a wonderful job. In fact, on one occasion, we arrived at the home of the deceased and the family fed us pizza. I paid my buddy $150 and he got free pizza too. Good deal.

This past Friday I was in the too-many-calls-with-too-little-personnel situation. Both of the friends I had called before were on vacation, so I called up another friend.

“Do you want to make $150 for an hours worth of work?”

“Sure”, he said. And then he asked, “Do I have to touch a dead body?”

“Yes.”, I said.

“Then $150 isn’t enough. I don’t want to touch a dead person.”, he stated.

I totally understood his position, told him I’d hold this over him forever and was able to find someone else who was willing to touch the dead.

So, how much would I have to pay you to help me go on a house call?

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

Some of the Mistakes I’ve Made as a Funeral Director

Funeral directing can be a lot like parenting.

If you have just one kid, you can usually keep the chaos at bay. When there are two kids, life can get hectic real quick. When there are three kids or more? The six-month-old is crying because he’s hungry, your three-year-old has magically found the fragile wine glass you had left out the night before, and when you ask your six-year-old for help, he starts to sass you because “he was right in the middle of his game.” All that happens in the span of a minute while you’re trying to cook dinner. For those of us that know the chaos, it’s not “can I stop the chaos”, it’s “how much can I limit the chaos?”

Mistakes happen. The three-year-old drops the glass, you drop the egg that you were about to crack for the quiche, and your six-year-old slams down the PS4 controller in protest, while you trip over the six-month-old and cut your knee on remanents of your broken stemware.

Running funerals are the same (without the quiche and the wine … although wine at funerals isn’t an awful idea). You have one funeral going, and it’s fairly simple. You can give your undivided time to just that one family. But all of a sudden, two more people die and now you have three funerals that you’re juggling, doing your best to maintain a semblance of order.

At this point, mistakes can happen. You do your best to create checklists and accountability measures. You do your best to overcommunicate the small details, but sometimes mistakes still happen

“Well, why don’t you just hire more staff? When you have too many kids, you get some help.” Oh, sage-of-the-internet-who-assumes-everyone-has-less-intelligence, let me answer that by saying this: things can get so busy all at once (which is the weird and unpredictable nature of this business) that it’s like going from one child to 10 children in a matter of hours. One minute you have too many staff at the funeral home, and the next minute you’re short staffed.

I met with a family the other week who instructed me to place a specific t-shirt at the foot of their husband’s casket during the public viewing. The day I was supposed to dress him, I got sick (I get semi-yearly days of utter brain fog that supposedly results from my Lyme’s Disease), leaving my grandfather to do my work.

In my sickened state, I forgot to tell Pop-pop to put the t-shirt at the foot of the casket. He put the t-shirt on the deceased.

I pulled myself out of bed for the funeral the following day, and when I saw what had happened, my heart sank. I apologized profusely to the family. They forgave me. That was a couple weeks ago and I’m still upset about it all.

But shit happens in life and shit happens in death.

Have you misspelled words in an email? I’ve misspelled words in an obituary.

Have you dropped a cup of coffee before? When I first started, I had a loaded stretcher collapse on me in the middle of a parking lot.

Have you ever confused your kids and put one to sleep in the wrong bed? Funeral directors might put a body in the wrong casket.

Have you ever thrown something in a fire, only to have that thing explode and cause 10K worth of damage? Well, I’ve missed a pacemaker or two in my career and reaped the consequences.

Maybe you’ve had a random collapsible stretcher loaded with a dead body and you were trying to get it into the bed of a van at a nursing home and it just wouldn’t collapse … and you tried and tried and a crowd started to gather as they watched you struggle to get the loaded stretcher into a van, and you just couldn’t and you almost started crying, and then after five minutes of trying to get it in the van you realized you were pulling the wrong leaver and you were almost at the point where you just wanted to crawl in the back of the van with the dead person and be dead too?

No? Just me.

As a parent, I realize my mistakes. I learn from them. I correct them if I can. And I tell my kids when I’m wrong. I don’t act like a know-it-all around my kids. I don’t give them the impression I’m a saint.

It’s hard for funeral directors to be honest with their mistakes because the whole process of putting a funeral together is SO EMOTIONALLY CHARGED. It’s not like I gave you Quarter Pounder instead of the Big Mac that you wanted. I can correct that mistake. We get one shot to do everything right. A mispelled name in an obituary can cause a firestorm. A pacemaker exploding in a retort can cost $10,000. Combing the hair the wrong way on the deceased can incite a flood of tears in the family. Everything needs to be done right.

But let me tell you from experience, it’s so much easier to be honest with your mistakes than it is to put together an elaborate lie or blame it on someone else. As tempting as it is to make excuses, I’ve learned that mistakes are human and apologies cultivate our humanity.

Love you all 🙂

P.S. If you’re feeling brave, I’d love to hear about your mistakes as well!

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

The Unknown Underground of Funeral Director Fight Clubs

Photo Author: emilykneeter

Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/emilykneeter/

License: Creative Commons Attribution License

Unlike the Chuck Palahniuk novel and subsequent movie, these fight clubs don’t happen in basements. They happen in Facebook groups. And unlike the movie, these Fight Clubs aren’t a way to let out existential steam…. these fighters are out for blood.

There’s SO MUCH ARGUING IN THE FUNERAL INDUSTRY!!! For those of you that are in closed Facebook funeral groups, you know. My god, you know. It get’s so serious in these groups that one faction will try to have the funeral licenses removed from another faction. One faction will report perceived offenses to the state board, hoping to get an enemy they’ve made in one of these Facebook groups fined or fired. And it’s worked. On more than one occasion, these Facebook funeral director fights have gotten people dismissed from their jobs, in some cases blacklisted. Livelihoods have been ruined by these kerfuffles.

It’s gone so far that one faction will hack another faction’s funeral home website. One faction will splinter off from one group to create another group that makes fun of the original group. One faction will bully the other to no end until the victim leaves the group.

It’s dirty. It’s drama. It’s a legit reality TV show where there are about a dozen main characters and the rest of us just sit back and watch the shit show.

Embalmers / funeral directors are like the Protestant / Evangelical / Baptist Churches. It’s common knowledge that Protestants / Evangelicals / Baptists have a history of breaking off from each other to create new churches that distinguish themselves by being different than the original. I know because I grew up in such a splinter church that broke off from another because we had a disagreement over the morality of the insurance coverage offered to the pastor. I learned a couple things along the ways about people, opinions, maturity, and unity in the midst of individuality.

If you’re in the funeral director fight club, you have absolutely no desire to hear me out. Most of you have already expressed your feelings of antagonism towards me. But for those of us who watch the funeral director fight club, here are my thoughts on where things can go wrong:

TWO DIFFERENT WAYS CAN BOTH BE RIGHT

You live in New York City. Your buddy lives in Nashville. You’re both driving to Orlando for a family vacation at Disney World.

The best way for your buddy is to drive the 75 straight to Orlando. The best way for you is probably 95 all the way down. It’s utterly silly for you to argue with your buddy by telling him that “95 is the only way to Orlando.” Because different locations require different approaches. And your starting point often determines your journey. As long as you both end up in Orlando, you did it right.

If you’re in funeral service, different locations require different approaches. It’s sometimes possible that both funeral director combatants are right because we all come from different towns, different cultures, and from a different set of expectations. What’s right for funerals in Parkesburg might be wrong for funerals in New York City. What’s expected of me in Parkesburg, might not be expected of me in Nashville. What you emphasize might be different than what I’m expected to emphasize.

DON’T BASE YOUR IDENTITY ON YOUR JOB

Because if you do, when people question your job, it’s like they’re questioning you. When they question how you do your job, it’s like they’re questioning how you live your life. When they question your job performance, it’s like they’re questioning your value. When they question your job acumen, it’s like they’re questioning your intelligence. When they disagree with how you do things, it’s like they’re disagreeing with your lifestyle.

If the funeral business is your identity, any discussion about how you do your job, the correct way to do your job, etc. becomes incredibly and intensely personal. Because I’m not just questioning your job, I’m questing your very identity.

When discussions about funerals become charged, I step away. Not because I don’t have an opinion, but because my identity is wrapped up in this business, but this business is not my identity.

FUNERAL FUNDAMENTALISM:

Here’s how religious fundamentalism works. There are three tiers of belief. The strong set of beliefs is what you could call “core beliefs”. These are the beliefs you hold most deep, and they usually have to do with who and what you love. Secondary to “core beliefs” is what you could call “values”. Values are practices and attitudes that we believe best enable us to serve our core beliefs. And the last category is what you might call “opinions.” This is the category where two people who share the same “core beliefs” and “values” simply differ and it’s no big deal (unless you want to make it one).

Fundamentalism doesn’t recognize these tiers. For the fundamentalist, everything is a “core belief.” Everything is worth fighting over. Opinions aren’t just opinions. Values aren’t just values. There is no context. There is no relativity.

The funeral fundamentalist has a problem with anything new. They have a problem with creativity. They have a problem with younger people offering a contextual perspective BECAUSE THE CORE BELIEFS HAVE ALREADY BEEN SET.

NARCISSISM

There’s a fine line between being a funeral director and being a narcissist. We’re called to be directors, to display confidence, knowledge, authority and strength during people’s weakest moments. But this environment that asks us to lead can too often enable us to self-enhance. We talk over our heads, project authority in situations that are best left to the family and tense up in disdain whenever we’re questioned.

Unfortunately, many funeral directors become narcissists (the funeral industry also has a tendency to harbor narcissists who gravitate towards the pomp and professionalism of funeral service). And while it would be easy to simply call these guys and girls “jerks”, the situation is usually more complex. For many, the tendency for funeral directors to become self-absorbed isn’t a product of nature, but of nurture. And recognizing the environmental factors that produce narcissism in funeral directors is a big step in making sure we keep focused on the heart of the funeral industry: serving others.

Until the stupid fighting stops, you’ll know where you can find me:

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

Why I’ve Stopped Being Nice (And Why You Should Stop Being Nice too)

Somewhere along the way, “being nice” became a supreme virtue in the United States. In fact, I think it may have taken the place of it’s predecessor … “being tolerant.” I never liked the word “tolerant”, and I’ve come to dislike the word “nice” for the same reasons I cringed at “tolerant”

“Tolerant” is an easy virtue to dislike, not because I think we should insulate ourselves from those who aren’t like us. Not because I’m racist, homophobic, or a religious bigot. I don’t like that word because all it does is ask us to “put up” with differences. I’m a white, heterosexual male. I don’t tolerate African Americans. I don’t tolerate homosexuals. I don’t tolerate women. Tolerate is something you do with an annoying younger sibling. Tolerate is what you do when you’re stuck in traffic and can’t do anything about it.

I open my heart to understanding a person and perspective that I can only see if I’m willing to put myself in someone else’s shoes. I don’t expect them to teach me (that’s not their job). But I do ask them questions and I listen to their responses because I’m interested in loving, understanding and celebrating differences, not just tolerate the differences. I celebrate my LGBTQ friends, POC, and religious diversity because I’m doing more than tolerate, I’m learning.

“Nice” is equally as empty a term.

As a funeral director, I’m expected to be supremely nice. Like, the nicest person ever. Like, picture the nicest person you know and then double their niceness is the kind of nice funeral directors are supposed to have. And there was a point in my career that I thought “being nice” was one of the main parts of my job. But, no longer.

I stopped being a nice funeral director when I saw how nice people tend to be enablers.

I stopped being a nice funeral director when I saw how nice people can’t communicate personal boundaries.

I stopped being a nice funeral director because I learned how to say “no.”

I stopped being a nice funeral director when I saw nice people getting burned out in this industry.

I stopped being a nice funeral director when I saw that grieving people don’t actually want a nice funeral director.

I stopped being nice when I saw how it’s as fake as the “how are you doing?” greeting.

Nice is what rich people are when they’re dealing with poor people. It’s the next step after tolerance. It’s tolerance, but with a smile on top. It’s what a CEO is when he does some PR with his minimum wage workers. It’s what white people are when they go to third-world countries. It’s how you act when a salesman calls your phone.

“Nice” is an okay virtue, but it’s so far down my list of important virtues, I don’t even try anymore.

I do, however, try to be empathetic, recognizing and embracing the humanity in those around me.

I do try to be vulnerable by making myself open to different perspectives, and honest about my own.

I try to be intelligent and educated, so that I know what I know and — more importantly — know what I don’t know.

I try to be present, fully engaged with the person(s) I’m talking to (And I’ll admit, this one is the one I fail at the most).

I try to be welcoming and hospitable by enabling people to be themselves around me and not what they think they should be around me.

I also to be true to myself and set healthy boundaries for my personal life and family.

But nice? Nah. I’m not trying to give off the impression that I’m nice. In fact, when people describe me, I hope “nice” is one of the last words they use, because I’m no longer trying to be a nice person or a nice funeral director. I’m pretty sure it’s one of the least important virtues if it’s a virtue at all.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

A Letter to the Good Funeral Director Working at a Bad Funeral Home

Author: Stephan Ridgway Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/stephanridgway/ Title: Raj’s funeral Year: 2011 Source: Flickr Source URL: https://www.flickr.com License: Creative Commons Attribution License License Url: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ License Shorthand: CC-BY

You joined this business because at some point in your life you realized that you could do something good in death care.

Maybe you lost a loved one, and you wanted to use your pain and experience to help others walk through the difficulty.

Maybe a funeral director’s love and helpfulness inspired you to want to be the same.

Maybe you felt called to the dismal trade, knowing that deep inside you resides a resilience that few other people possess.

Whatever your reason for working in death care, the end was clear: you pursued this profession because you knew something good could come of it.

Then you started to look for a job. And the market was much tougher than you realized. The business was harder to crack than you could have imagined. The family-run funeral homes that you wanted to work for didn’t have any open positions. And the large, machine-like homes only offered positions with tough hours and cheap pay.

Whatever your story, you either ended up at a funeral home that you thought was great, or you ended up at a funeral home that was less than ideal.

*****

For some of you, you worked your way up from the bottom. You put in your due. The night shifts. You worked on holidays. You cleaned the prep room. You parked the cars. You mowed the lawn. You worked with Larry, the son-in-law of the owner who constantly makes off-color and sometimes sexist jokes.

Or maybe you got stuck with Robert, the owner’s nephew who slacks off, rarely pulls his weight, and constantly complains.

Then there’s John/Johanna, the supervisor. When he/she’s in front of the public, he/she’s the consummate professional: caring, compassionate and consistent. But when he/she’s out of the spotlight, his/her ability to supervise is nowhere near his/her ability to be a funeral director. His/her temper is short, he/she blames failures on everyone else except himself/herself and the only time you’ve ever seen him/her smile is when he/she’s bragging about himself/herself or leaving for vacation.

You’ve finally worked your way up the ladder and now you’re making arrangements … doing the thing you’ve always wanted to do.

Except, you’re not just expected to care for people, you’re expected to care primarily for the bottom-line of the business. The tag-line of the funeral home would imply that families come first, but the truth you’re realizing more and more is that it’s really the dollar.

Upsell the caskets.

Upsell the packages.

Push embalming.

Obfuscate, obfuscate, obfuscate so that families don’t know the money saving options.

Use lines like, “This is the casket your loved one deserves.”

And, “This casket honors your dad’s life like no other.”

Or whatever line the kids are using these days.

*****

First off, if this is you, I’m sorry.

Unmet expectations are difficult to digest. Lousy supervisors make a difficult job even more demanding. And finding out that — for some funeral homes — it really ISN’T all about service … finding out that many of these dudes are in it for the money … that discovery is enough to deflate the reason you pursued this career in the first place.

There’s a couple options for you at this point: Sometimes, the good funeral director in a bad funeral home holds onto his/her job. They kowtow to the system because — let’s face it — it might not be the best income, but it’s a job.

Some quit. Let me correct myself … many quit. They’ll go looking for a better funeral home with better people. And those funeral homes are out there. They really are.

Others will try to start their own funeral home, or buy out an old one so that they can implement their original vision of what death care should look like.

But for many, they wash their hands of this industry and make the healthy choice to find another profession.

To the good funeral director currently working at a bad funeral home, I’m not going to promise you that it get’s better. Some things don’t get better. Some things need to be burnt down (I’m talking figuratively of course). Some things can be changed, through hard work and a labor of love, to be something better. Some things need to be abandoned.

Whoever you are. Wherever you’re at. Let me say this: death care needs you, but you don’t need it.

If you entered this business with a heart to serve, YOU are what families need when they encounter a sudden death and have minimal funds. YOU are what families need when they just want someone to honestly tell them their options. YOUR ability to bring some sense of order to chaos is exactly what we need.

But, let me be clear: YOUR DESIRE TO SERVE DOESN’T NEED THIS INDUSTRY. That heart to serve can play out in so many different professions. EMT. Nursing. Coroner. Medical Doctor. Anywhere, really. Because the world always has a shortage of people who genuinely want to help others, and if you genuinely want to help others, you’ll never have a shortage of opportunities.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):