Funeral Directing

This Is Hard for You to Understand

I picked up the phone with my rehearsed, “Hello. This is the Wilde Funeral Home. Caleb speaking.” The voice on the other end says abruptly, “I have a problem … my son-in-law was killed in a motorcycle accident yesterday.”

Now that I know the nature of her call, the next five or six sentences are as rehearsed as the first.

“I’m so sorry for your loss.”

“Thank you” she says.

I pause … waiting to see if the silence elicits any farther response; and, at the same time I’m contemplating if I should deviate from the script and ask her about details of the death.

Keeping with the script, I continue on, inquiring about the hospital he’s at, the name of her daughter, her daughter’s phone number and then the hardest question of them all:

“Do you know if you want embalming or cremation?” I say with hesitation.

And what proceeded was her only scripted response.

“It depends on the condition of his body. The coroner told us he slammed into a tree without his helmet on, but they wouldn’t tell us anymore. If he’s bad … cremation. If he’s okay … embalming.”

We then went over the plan of action, which consists of me calling the hospital to see if her son-in-law’s released, calling the coroner to inquire about the condition of the body and then calling her back to let her know a time she could come in to the funeral home and make arrangements.

I called the coroners.

Got the release from the hospital.

And an hour later I was standing in the morgue unzipping the body bag to see if the body of this 40 year old man was viewable. It was the back of the head that hit the tree … something we could fix for his wife and four young children (ages 5 to 13), so they could see their husband and daddy one last time.

15 hours of restoration. He still didn’t look right. Dead people never look right. We’re so used to seeing them alive that dead is never accurate … but this was different. This was a motorcycle accident that threw a man into a tree.

We gave the wife the choice to continue on with the public viewing or close the lid and she chose to keep it open, sharing the reality and source of her pain in all its distortion … sharing it even with her four young children and all their schoolmates that came out in support, many of whom saw unperfected death for the very first time.

The scheduled end of the viewing came and went but people kept coming to view.

Finally the last person filed past the casket and the family knew the time to say their last good-bye had approached.

The viewing was held in a church, with the casket positioned at the front of a totally full sanctuary. As a way to provide privacy to the family, we turned the open casket around so that the lid blocked the view from the pews … creating a private space where tears could be shed in all their honest shock.

The sanctuary echoed with the cries of four children and their mother.

And the sanctuary echoed with the cries of four weeping children and their mother … making time stand silent.

Until the grandfather came up to the casket, wrapped his arms around the children and said, “This is hard for you to understand.” The tear soaked porcelain skin cheeks. The last look of their father’s physical body save the memories their young minds have stored.

In those moments as the sanctuary resounded with the cries produced by an inexplicable death, there wasn’t a person in the room who understood.

Yet all tried to understand. All grasped for an explanation.

In these moments — as we watched these young children — we all became like them. With all the well intended cliches emptied of meaning, we allowed our minds to reconcile with what our hearts were telling us: we simply can’t understand something that doesn’t make sense.

Hi! My name is Caleb. I Carry Death.

Tears in the produce aisle of Wal-Mart.

Hugs at the gas station.

An affectionate gaze at the pizza shop.

Created by death.

To you, I’m all the depth without any superficial.

The person who helped you walk through the shadow.

The person who stood with you as you said your last goodbye.

As the lid was closed, I was there.

I am not your friend.

I am not your bar buddy.

We will never talk sports, or politics or local gossip.

I am almost your brother.

Almost family.

I am your funeral director.

And I carry your death experience.

I carry in my own heart your grief, you insecurities, your hardest moment.

I remind you of him, of her … in many cases, I remind you of them.

I carry the depth. Your deep is in me.

The depth of this community is my association.

Everywhere I go, I carry death.

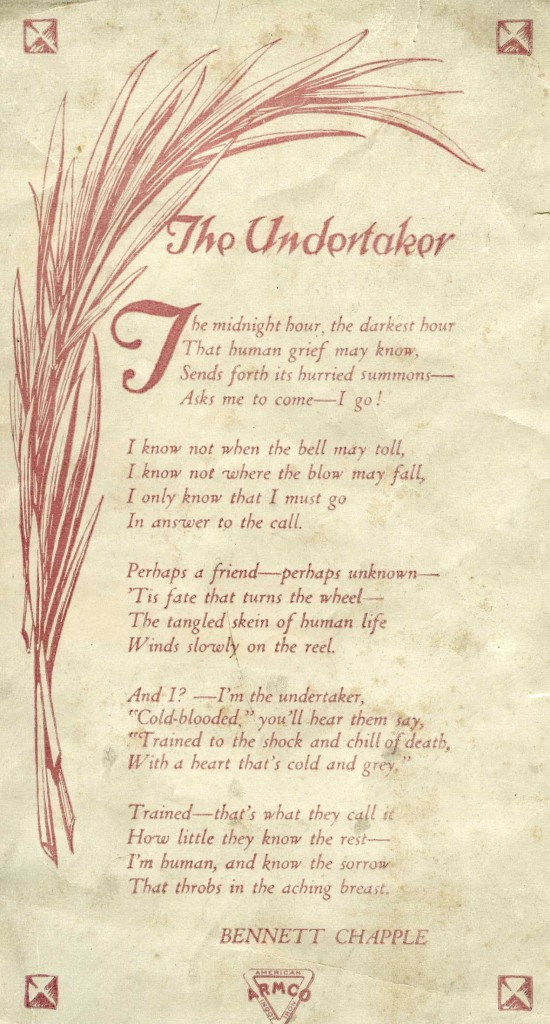

A Poetic Homage to Undertakers

My dad found this in the funeral home. It looks like it could easily be over 50 years old.

It captures the tension that exists in the funeral business … the tension of being so involved in humanity yet so easily perceived as cold hearted and un-human.

The Why That God Doesn’t Answer

This blog has afforded me a number of privileges, the greatest of which has been the connections I’ve made with those in the blogging community who are grieving. Grieving hard.

Young woman who have lost their spouses. Suicides. One man whose wife was raped then murdered. Miscarriages. Then, there are the slow deaths from dementia / Alzheimer’s / cancer, and the limbo of wondering, “What is wrong?” as the dementia turns to anger, abuse and eventual death.

Tragedies. All. Darkness I’ve been privileged to feel.

Many have expressed that they’ve wrestled with the “why” that God doesn’t answer.

The “why” that expects a response. The “why” that pastors say will one day be answered in the next life, when our perspective is clearer and our hearts are closer to God. The “why” that some Christians claim is soothed by the soft, quiet voice of the Holy Spirit. And others dismiss because they know with certainty that death was somehow “God’s will.”

Yet, for many believers, and nonbelievers, the answer to this why cannot hold out to the next life. For too many this “why” is answered, not by the soft, quiet voice of the Spirit, but by the darkness of silence.

A “why” that is only multiplied by silence. A “why” that grows into disbelief and continues to be solidified by the silence that started it.

*****

The other week we held the funeral for a 50 year old that was killed in a motorcycle accident at our funeral home.

What made this particular situation more tragic wasn’t just the way he died, but the fact that he left his wife, young son and even his father behind.

As I was parking the family vehicles in the procession line, I spoke with the deceased’s mother-in-law for about 10 minutes.

She wanted to talk and I wanted to listen.

She explained to me that, as there were no witnesses to the accident, the theory is that he lost control of his cycle as a result of a deer jumping out in front of him, causing him to attempt an evasive maneuver and lose control of his cycle.

The mother-in-law explained that nobody knows for sure a deer caused him to lose control – as there were no witnesses — but given his superior riding ability, his familiarity with the specific road he was on, and the fact that there were skid marks at the place of his accident all seem to support the theory that he was lost control while attempting to avoid something … that something probably being a deer.

Unknown and unexplainable deaths can often lead to a grey and confusing grief. I’ve noticed that grief works its way through a person in a slightly healthier manner when it has some explanation, but when there isn’t an explanation … it just sits like a morning fog.

*****

The forever question of “How did he die?” was answered not with a “real” answer, but with an answer that sufficed … that somehow made the grief that would otherwise be grey and confusing into something something slightly more healthy. It was an answer that we “imagined” from the best evidence we could supply. An answer from our own imaginations.

And I wonder how often the heavy “whys” of death and God aren’t just answered by our own imaginations. I wonder how often we simply speculate based on our knowledge that God is good, that death is bad, the man is somewhat free to mess up … that s*** happens. And after convincing ourselves numerous times over, we simply come to believe that our imagined answer is “the truth.”

The silence to the “why” is so maddening that we just fill it with answers of our own making.

It’s convenient.

It’s easy.

It works.

And maybe it’s somehow healthy for us.

And then I wonder if the silence to our “why” might just be due to the fact that God has no answer. Maybe he’s not there at all. Or, maybe we’re asking a question that’s inspired by something that has no response.

A Beeping Day in the Funeral Business

I had worked a 70 hour week, capped off with a Saturday funeral that lasted (viewing to burial) 7 hours (most last 3 hours).

I got home at five, settled in by watching Penn State football and then my cell phone rang.

“Caleb,” it was my grandfather’s voice, “we have a call at Such and Such Nursing Home.”

I grabbed my suit, put it back on, drove to the funeral home, loaded the collapsible stretcher into the hearse and off I went to Such and Such.

I’m tired.

Bleeping grumpy.

I pull up to the front door of the nursing home. A new nurse greets me and tells me she doesn’t want me “dragging the body through her wing.”

Too tired to persuade her with a smile, I jump back into the hearse, drive around to the other wing, and as I pull up there’s a younger man wearing a Phillies shirt, maybe a little older than me sitting in his electric wheel chair. As I get out, I try to cut the I’m-a-funeral-director-here-to-pick-up-a-dead-person awkwardness by striking up a conversation. I can tell rather quickly that he’s not a visitor. He – the not so older than me person of the wheel chair – is a patient.

His speech is slurred and slowed, but his mind’s still working as he jokes with me about the choking Phillies. And as we converse, I try to open the door to the nursing home but it’s locked, which kinda upsets me cause as I peer through the door I notice there’s no one around. No one.

The anger that starts rushing through my arteries is slowly abated by a “I dot da toad for da door.” He gives me the passcode and I give him a “See ya later” as I expect him to be gone when I come back.

But 45 minutes later he’s still there.

Sitting.

Alone. He’s a little older than me.

I open the door and park the collapsible stretcher on the porch as I open the door on the hearse and he says, “So, you dedided to go intu da bisiness, Caleb?”

A question with an obvious answer, but it wasn’t meant to be answered … it was meant for awareness.

There was only one person I knew who was wheelchair bound that was my age.

In high school one of my good friends got drunk with one of his buddies, drove his sports car, wrecked it, flipped it, but not before throwing his buddy/passanger out of the vehicle, paralyzing this guy.

“Jackson,” I said. “I remember you.” Which was the answer he was looking for.

And then I continued with some bitching and moaning about working 80 hours this past week, which comes so naturally at times that I was able to hold my own private conversation inside my head, thinking, “How ungrateful am I complaining about working when this guy sits all day, mostly paralyzed.”

I can sometimes do two things at once. Rarely can I do three.

But here I tried: I was talking to him, trying to think about what his life’s like and then, for honor’s sake, I started to load the body into the hearse. And it wouldn’t go.

The collapsible stretcher wouldn’t collapse.

I tried to put the body laden stretcher into the hearse once, twice and on the third time I pushed extra hard and … BEEP, BEEP, BEEP, BEEP, BEEP ….

Somehow when I had pushed the third time I must have squeezed the panic button on the keyless entry device in my hand and had begun to ruin the quit peace of the Such and Such Nursing Home.

It was so loud!

I hit the panic button again thinking that would stop it. Nope. Tried the “unlock” button. Nope. And it was here I tried the fourth time to get the stretcher into the van to no avail. Dilemma. I thought, “If I start the car, it will probably stop … but if I start the car, I have to leave the stretcher hanging out the back of the hearse.” But I had no choice.

We were sitting on the top of a hill and the worst case scenario was running through my head … a scenario that – if it had happened – I wouldn’t be telling it here, on my blog. But the fear of losing a stretcher down a forty foot hill with a decent sloop scared me enough to try and secure it. I then ran to the driver seat, turned the key … nope.

So I quick get out and go back to attending the stretcher all the while I’m expecting a nurse or supervisor to come out and rip into me.

For some reason I hit the panic button again and while the alarm goes off, in place of it I hear this loud, almost barking kind of a noise coming from the wheelchair: “Arf! Arf! Arf!”

Jackson’s barely able to suck in air as he lets out his massive belly laughs one loud yelp at a time. He finally gets his breath, I finally get the body in the hearse and he starts yelling, “I wish (gasps for air) I tad a camera (sucks in another deep breath) I’d put dat on (deeeeep breath) dootube!”

I had made his day … maybe his week.

The beeping crescendo of my awful week was the laughing pinnacle of his.

And his laughter somehow made all the problems of my week fade away.