Funeral Directing

On Being Friends with an Undertaker: 10 Things You Should Know

One. We’ll Disappoint You

I suppose every friend will disappoint you once in a while; but funeral directors will probably do it more often. We might miss your birthday party, we might have to leave in the middle of dinner.

Death has this way of keeping an untimely schedule. And as death’s minions, we’re tied to that schedule. Whether it be in the middle of the night, or in the middle of your wedding, when death calls, we have to respond.

Two. We Might Ask You to Help Us on a Death Call or on a Funeral

Every once in a while, we need some help at work. And don’t be surprised if we end up calling you. Most of my friends have helped me once or twice on a death call. One specifically (ADAM!!!) refused to help, which is fine … even though I was willing to pay him. If you don’t want to go on a death call with your funeral friend, you can use Adam’s line, “No amount of money is enough to touch a dead body.” Fair enough 🙂

Three. The Conversation Starter “What did you do today?” Isn’t a Good Question to Ask a Funeral Director

Especially around dinner. We might make you lose your appetite. Or we could just make you depressed.

Four. Keep Pursuing Us

The schedule of our work can be very rigorous. And free time can be hard to come by. Sometimes we don’t get to see our families very often and the little free time we have, we want to spend it with our partner and children. And sometimes we just have to say “no” when you invite us out to dinner or a ball game. But don’t be hurt by our “no” and please keep asking us to visit with you. Funeral directors need friends too.

Five. We Tend to Party Hard

There’s a variety of reasons funeral directors like to have fun; but probably one of the main reasons is that death has made us realize the fleeting nature of life. And some of us (like myself) don’t naturally fit into the dress suit and tie persona; so when we’re out of the suit and tie, we let our hair down.

Six. Unicorns

Every single funeral director in the entire world loves unicorns. So if you don’t know what to get us for Christmas or our birthday, buy us a unicorn.

Seven. It’s Okay If We’re Slightly Depressed

If you’re hanging out with a funeral director and you notice they’re down, it’s not a reflection on you. Most of the time we are the stable minds in the midst of the bereaved unstable souls. But sometimes — whether it be the death of a child, or a particularly tragic death — our job throws us down.

Eight. We Tend to be Givers

The nature of our business is service. And many of us enter and stay in this business because we enjoy serving. This “servant hearted” nature bleeds out to our family and friends. We like to give things, whether it be paying for your meal, or giving nice Christmas gifts, or nice cards. Accept our gifts. It might be hard. But gifts and service is how we show you our love.

Nine. Yes, We Might Have a Morbid Sense of Humor

We’re notorious for having an odd sense of humor. So be forewarned.

Ten. We Need You.

Our family and friends are our life. Literally. Our jobs are dark and at times depressing. You are the light that gives us life. And in a job that consumes so much of us, if we’ve invested in you it means that we really value you. Sometimes, you — our friends and family — are the only thing that keep us grounded. Even though it might be hard for us to show it, we not only love you, but we need you in our lives.

How to Speak the Language of Grief

You walk into a house full of fresh grief. It’s fresh because the death just occurred. Your best friend’s husband went out to the bar last night, drowned his hard day in hard drink and he never made it back home. Fresh. Because both you and your friend have never experienced death this close.

You open the door like you have so many times before, but this time the familiarity of the house is unexpected different, dark and lonely. What once housed parties, life and love now houses something you’ve never known before. Like a river, everything is in the same place it was when you last saw it, but this home has changed.

You see your friend’s children sitting on the sofa, staring into space.

You ask them, “Where’s your mom?”

And as you reach to hug them, they snap back to reality and whisper, “Upstairs.”

Each step brings you closer to what you know is only an apparition of your friend. The nerves build. Fear begins to build. You repress it as you ready yourself to meet your closest friend who has all of a sudden become someone you may no longer know.

“Can I come in?” you ask. No response.

You push open the cracked bedroom door and see the body of your friend collapsed on her bed, with used tissues surrounding her like a moat.

You tip-toe into the room, slowly sit down on the bed, and not sure if she’s awake or asleep, you reach for your friends shoulder and begin rubbing her back. Her blood shot eyes open, look at you and then, they slowly look through you.

You fill the weird silence with an “It’s going to be alright”.

“It’s not”, she whispers. “I’m alone with two kids and no job.” Her voice suddenly raises as anger courses through her body, “Why the f*** would he do this to me?”

The curse word chides you into recognizing that you’ve not only misspoken, but you’ve spoken too soon, so you decide to wait in silence. She starts to cry. You respond to her tears with your own. Even though you want to respond with words, you know this isn’t the time for words. There’s no perfection words here. There’s no perfect anything here. And so you wait.

You stay. Listen. Silence. You take her pain into your soul. Hours pass. She rises out of bed and makes the children dinner.

You’ve spoken, not with words or advice; not by trying to solve the problem; nor by placing a limit on your time. You’ve taken the uncomfortable silence, allow the grace for tears, for brokenness; you’ve allowed yourself to sit in the unrest without trying to fix it.

With your presence. With your love. In your honest acknowledgement of real loss, you’ve spoken the language of grief.

Although the language of grief is usually spoken in love, presence and time, sometimes it’s spoken in words. And when it is, here are five practical “do”s and “don’ts”

The “DON’T”S:

1. At least she lived a long life, many people die young

2. He is in a better place

3. She brought this on herself

4. There is a reason for everything

5. Aren’t you over him yet, he has been dead for awhile now

The “DO”S:

1. I am so sorry for your loss.

2. I wish I had the right words, just know I care.

3. I don’t know how you feel, but I am here to help in anyway I can.

4. You and your loved one will be in my thoughts and prayers.

5. My favorite memory of your loved one is…

Why Funeral Directors Become Narcissists: Seven Reasons

There’s a fine line between being a funeral director and being a narcissist. We’re called to be directors, to display confidence, knowledge, authority and strength during people’s weakest moments. But this environment that asks us to lead can too often enable us to self-enhance. We talk over our heads, project authority in situations that are best left to the family and tense up in disdain whenever we’re questioned..

Unfortunately, many funeral directors become narcissists (the funeral industry also has a tendency to harbor narcissists who gravitate towards the pomp and professionalism of funeral service). And while it would be easy to simply call these guys and girls “jerks”, the situation is usually more complex. For many, the tendency for funeral directors to become self-absorbed isn’t a product of nature, but of nurture. And recognizing the environmental factors that produce narcissism in funeral directors is a big step in making sure we keep focused on the heart of the funeral industry: serving others. Here are seven factors that tend to produce narcissism in the funeral industry and therefore keep us from being the public servants we’re called to be.

One. Power.

Families come to us in despair, their minds clouded by grief and the unknown. They pay us to be the stable minds. And they give us power. They give us power every time they trust us with their deceased loved one and their grief. And when they give us that power, there’s a certain satisfaction that comes with treating that vulnerability with as much honor as we can.

But sometimes that power can bloat our egos.

Two. Praise.

Being told, “You’ve made this so much easier for us.” or, “Mom hasn’t looked this beautiful since she first battled cancer”, or “You guys are like family to us” means a lot to me. It’s important to know that what we’re doing is meaningful for the person we’re doing it for.

That verbal affirmation is a big reason why I continue to serve as a funeral director.

But that praise doesn’t mean we know it all. It doesn’t mean we’re never wrong. And it certainly doesn’t mean we’re the unquestioned authority on all things funeral.

Three. Pomp.

We get up in the morning, put on our nice clothes, park in the parking lots of our grandiose funeral home and pull out our grandiose Cadillac and Lincoln funeral coaches. Pomp has a tendency to make us think we’re important and to make us forget that all that pomp isn’t for us, it’s for the family we’re serving.

Four. Lack of Criticism.

So, when people ACTUALLY do question you, when your beliefs are questioned and when you’re criticized, it’s important for us to remember that we’re here to help families, not give them all the answers. Our pride isn’t in ourselves. Our pride is in service; and criticism — as hard as it is to hear — is often a very healthy way to enhance our understanding of how we can better serve.

Five. Secrecy and Professionalism.

Leon Seltzer writes, “(Narcissists are) highly reactive to criticism. Or anything they assume or interpret as negatively evaluating their personality or performance. This is why if they’re asked a question that might oblige them to admit some vulnerability, deficiency, or culpability, they’re apt to falsify the evidence (i.e., lie—yet without really acknowledging such prevarication to themselves), hastily change the subject, or respond as though they’d been asked something entirely different.”

The secrecy (which is often clouded in a pretentious form of professionalism) of the funeral industry often allows an out for narcissists. If their work is questioned or criticized, they will often pull the professionalism card

Six. Micro Markets.

There’s nobody that knows the people in your community better than you. You are the best person to serve those that walk through your door. YOU have poured yourself into the community, you have give your holidays, your late nights, your overtime for people. And sometimes we feel like we know our market so well that we know it better than the ones we serve. I’ve seen it happen. You may have invested decades into your community, but that doesn’t mean you these are “my families” and “my people.”

Seven. Education.

In a culture of death denial, we are one of the few segments of the population that think about death on a regular basis. And in a culture that rarely thinks about death, it doesn’t take much knowledge to feel like a “death expert”.

Let’s just make a couple things clear: funeral directors aren’t psychologists, we aren’t philosophers, we aren’t grief experts and because there’s such a vast array of funeral customs and practices, we aren’t even funeral experts. Sure, you know your demographic, but your demographic is a very small sample of global funeral customs. Narcissists have grandiose sense of self-importance and often times this leads to funeral directors thinking they are the end all be all of death education.

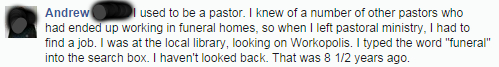

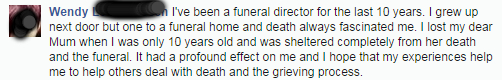

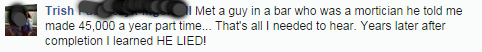

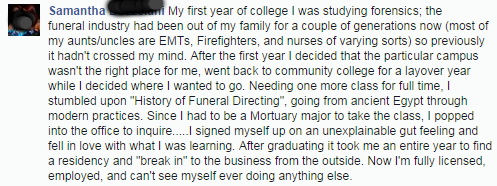

Why Normal People Enter Death Care: 20 Short Stories of Inspiration

I asked this question to the Confessions of a Funeral Director community:

If you’re in (or going to be in) the funeral trade, what reason(s), experience(s) and/or event(s) inspired you to take the plunge?

These 20 very short stories help dispel the idea that funeral directors are innately money-hungry creepy people. Creepy people who stuffed their first piece of road kill at the age of 10. People who were born and wrapped in a black baby blanket and put in a coffin shaped crib with hearses and trocars dangling from our crib carousels.

Yes, death makes us different but most of us entered death care as normal, good-hearted people who want to make a living while making a difference.

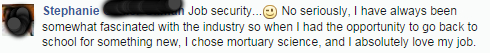

1.

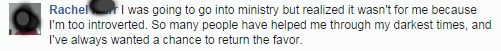

2.

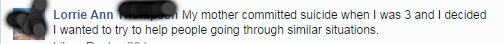

3.

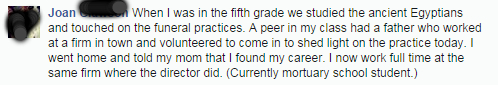

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

FIVE MYTHS ABOUT FUNERAL DIRECTORS

Today’s guest post is written by Pastor Dieter Reda:

Over the last 34 years of pastoral ministry I have conducted hundreds of funerals. That means I have worked with scores of funeral professionals. My ride to the cemetery is usually in the lead car, which normally is driven by the director who is in charge of a particular funeral. Sometimes it is a short ride, but there have been some longer trips also to distant cemeteries or to burials in a rural cemetery way out in the boonies. The conversations have ranged from the polite professional, to swapping stories, to the occasional theological conversation. In any case, when you spend time in close confinement with someone on a repeated basis, you get to know something about their personality and what makes them tick. And then there were two years of hiatus from ministry; time that I needed to heal some personal wounds. In that time I worked first at cemetery sales, and then spent a year in a corporate funeral home. That presented even more opportunity to spend time with funeral directors up close.

The majority of the men and women I worked with are capable and compassionate professionals, who believe strongly in what they do, and sincerely try to help the families they serve. For some however it is just a job, and a very small minority should probably be in a different line of work. But that is true of all professions, including the ministry. Some of the people I worked with, I would trust to look after my family, and in fact one of them did. A very few I would not trust with the burial of my dog. Several have remained my friends to this day.

Many directors struggle with the myths and stereotypical generalizations about their work and their role. . Here are some of the more common myths and my response based on being up close and personal with a number of these professionals.

- Funeral Directors are only in the business for the money. That is partially true for almost anyone who is gainfully employed. Everyone would like fair compensation and many if not most of us think that should be as much as possible. Some of the funeral directors that I was close to revealed their income level to me and frankly I was appalled how little they are paid. I would suggest that it takes a special kind of person with a deep commitment to what they do, to work the long hours that funeral professionals do, which often includes holy days and public holidays on which the general work force is paid not to work. Like doctors, nurses, police, fire fighters, ministers and others, a funeral director often has to work when everybody else is having fun. Some of the others are paid double time for those efforts, but not the funeral director. When a death happens on Christmas Day, we expect someone to be available when we call the funeral home. If you want to be in something “just for the money”, the funeral business is not the place to be, unless you happen to own a funeral home. Nowadays many of them are owned by huge corporations, and yes they are very profitable.

- Funeral Directors are opportunists who prey on other peoples’ vulnerability. The assumption is that funeral homes take advantage of the fact that you are emotionally distraught as you come to make final arrangements and that therefore they will manipulate you into spending as much money as possible. While there are unscrupulous people in every profession, the truth that I have observed is that most funeral directors prefer that the principal mourner not be alone when it comes to financial decisions such as what casket to purchase. Most encourage that other members of the family, or perhaps even close friends take part, in order to avoid making emotional and unwise decisions. I have known more than one director who has persuaded someone to consider a more affordable option. That is why they also advocate making pre-arrangements at a time when one can carefully consider what is affordable.

- Funeral Directors are aggressive sales people. My experience has shown me that actually very few of them are skilled sales people. Most of them are “order takers” who try and find what it is that the customer wants, and then make that happen. I have seen the “used car salesman” type of funeral director only in the movies. In real life, a mortician couldn’t stay in business if he or she had a reputation about such antics.

- Funeral Directors are insensitive Fakes. I actually met one, but only one such professional. It seems that no matter where you saw him, he had weepy eyes that actually could produce tears on demand, and he always spoke in that soft stained glass whisper. We don’t expect funeral professionals to pretend to be mourners. I have always appreciated the ones that are respectful in their demeanor, even when the funeral involves rituals that are contrary to a director’s beliefs. I don’t expect a director to sing the hymns, recite the creed or the prayers, but I would appreciate it if he did not whisper and joke with a colleague during such moments, and yes I have seen that too! When a family is a gravesite, the worst sight for them is to see the funeral staff standing behind the cars laughing and joking during the service, only to put on the soft whisper when they hold open the door to the limousine. That is fake, but according to my observation that is the exception, rather than the rule. Most of those that I have observed are respectfully professional, and others are genuinely compassionate.

- Funeral Directors are Experts about Everything on Death and Dying. To be honest, some of the younger newly licenced directors do come across that way. I had to remind one young colleague that he often served people who were much more educated than he, and know more about psychology, grief, to name just a few things. While more and more funeral directors now have university degrees, here in Ontario the educational requirements are minimal. A High School diploma will get you admitted into the “Funeral Services” program at one of the colleges in Toronto. This involves 1 year (2 semesters) of classes and embalming labs, followed by a 1 year apprenticeship in a licenced funeral home, after which time the provincial licence exam is written. The licence entitles you to embalm, and to sell and make at-need funeral arrangements. It does not however make you an authority on grief counselling, financial and estate planning, medical issues, and many other things that some funeral directors like to pontificate about. Neither does it make you a theologian, although I was surprised by how many former ministers ended up in the death care industry.

I have come to the conclusion that it takes a very special person to pursue this calling. Someone with a unique set of skills to deal with both the living and the dead. My advice: get to know one, preferably before you need to.

*****

Dieter Reda has been an ordained Minister for the past 34 years and served various churches in central and western Canada. Since 2003 he is senior pastor at Mission Baptist Church in Hamilton, Ontario (Canada). His blog of pastoral musings on various issues is at www.dieterreda.com and you can follow him on Twitter @Dieterreda.