Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

The Tragic Story of the Generous Funeral Director

The following is a fictitious story based on all too real trends in the funeral industry.

****

I sit down in Larry’s office and do a quick look around before we start. Framed pictures of his three girls, a couple grandchildren and his wife are standing scattered on his desk. Golf clubs lie in the corner. A giant professionally drawn water color of the “Wellington Funeral Home” hangs on the north wall. And directly behind Larry’s desk a certificate is prominently displayed stating, “The State of New York Board of Funeral Directors hereby Licenses LARRY WELLINGTON to Practice as a Funeral Director.”

That photo, and others, are a couple weeks away from being removed. The “Wellington Funeral Home” had been the last of the family owned funeral homes in this town; that is, until Larry sold it to a corporation. And that’s why I was here. To cover the story for our county newspaper. An economically depressed region, Larry’s business represented one of the few success stories in our area. He was well loved by our town, respected by his business peers and his thundering golf swing had become a tall tale at the local courses.

Larry sat behind his dated metal desk and I in front of it, we know each other well enough that I bypassed the bull and got straight to the point, “Why are you selling?”

“I can’t do it any longer. After 30 years of service, it’s become a business. And I’m done with it.”

“Let’s start from the beginning,” I interrupted. “Why does a 20 year old Larry Wellington decide to become a funeral director?”

“Thirty some years ago my mother died.” Larry told me how his mom – a single mother (his dad was absent all throughout his life) – had been his rock. “She was everything to me” were his exact words. Worked two jobs as long as he could remember and sacrificed everything for Larry – her only child.

“When she died suddenly on that warm July evening – God, I can remember that phone call as clear as day — I had absolutely no idea what to do. Someone suggested that I call what used to be “Thomas Funeral Home” up in Hamilton County. So I called Dale Thomas and he guided me through the whole process of arranging the funeral, settling Mom’s accounts and he would even check up on me months after the funeral was over.”

“About six months after Mom’s death, I had her life savings in my name and I knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to be like Dale Thomas. I wanted to be a funeral director. And I used Mom’s money to go to the McAllister Institute of Funeral Service. I soon met my wife, I graduated McAllister and we moved here – Joan’s hometown – and I started a funeral home with the heart of an angel.”

At this point, Larry became reflective, his face relaxed in a pensive stare. He had been telling me his story like he was reading it out of a book … the facts of his life. And we had reached the point in his story where the facts began to blend with his current reality.

“I started this business with angel’s wings.” He waited, looking at nothing as though he was looking at a vision of himself that only he could see. “After years of being too generous, I’m tired.”

Slowing moving back to a fact teller, Larry explained how his lower prices both helped the success of the start up funeral home and laid the foundation for its demise.

“No professional service charge for children.

If they didn’t have money, I’d work with them.

If there was no insurance policy, I’d trust them.

Before I knew, I had a target on my back, “If you can’t pay, go to Wellingtons.”

At first, I didn’t mind getting beat out of a funeral. Over time — with nearly 7 percent of my customers not paying their bills — it started to wear on me. So, if I didn’t know the family, I’d ask them a litany of questions about payment and money. I then started asking people to pay all the cash advances up front. And even with the unpaid bills, I was still making a sustainable living, but my faith in humanity and my ability to tolerate deception was beginning to reach an unsustainable level.

About a year ago I buried a gentleman in his 50s who died in a car accident. Tragic. Very tragic. I didn’t know anyone in the family … they were from this side of Tioga county. The family – in their distress? – looked me in the eye, told me they had the money for the $10,000 funeral they wanted (real nice Maple casket, the best vault, etc. … they could’ve gone A LOT cheaper) and after the burial I never heard from them again.”

“I lost my wings after that” he said. “Oh, I had been beat before, but this was the one that broke me.”

Moving back to the reality that is, Larry looked at me intensely and said, “I came to a place where I’d been beat — unpaid — by so many people that I was going to have to charge them up front for their funeral. And I couldn’t do that. So I sold it to people who could.”

He continued, “I got in this line of work because I wanted to serve people, but I’ve become too jaded. Too many people are taking advantage of me. And I can’t force myself to take advantage of them.”

And with eyes that begged me for an answer, he asked, “What would you do? What would you have done?”

I didn’t have an answer. We looked at each other for a couple seconds and right before it started to feel awkward he continued, “_____ Funeral Corporation offered me enough for an early retirement and I took it.”

And the tragedy is this: It’s hard enough to run a business in this world. It’s nearly impossible to do so when you’re uncompromisingly generous. And yet, it’s the generous business people that we so desperately need.

Larry will be moving out of his funeral home and a new Funeral Corporation will be moving in. The funeral home name won’t change, but you won’t find Larry in his office. Instead, he tells me, you’ll find him on the greens, creating more tall tales on the local golf course with each long drive.

10 Ways Funeral Directors Cope with the Stress of Death

Here’s 10 coping methods I’ve seen funeral directors use.

The first five are coping methods that are negative techniques.

The last five are positive coping methods. One or more of these methods MUST be used if a person is to stay in this profession AND maintain a healthy personal and family life.

NEGATIVE COPING METHODS

One. Displacement.

Funeral service is a business that is both uncontrollable and unpredictable. Since funeral directors can’t control death and death’s schedule, we attempt to control those things and/or people that we DO have power over. We too often take out our frustrations, fears and anger on those closest to us.

Two. Attack.

And we often displace those emotions on those closest to us with some kind of aggression. In an attempt to cope and find a sense of control in our uncontrolled and unpredictable world, we will often emotionally and verbally manipulate and control our family, co-workers, employees, associates and those closest to us, making us seem nearly bi-polar as we treat the grieving families that we serve with love and support and yet treat our staff and family with all the emotional turmoil that we’re feeling inside.

Three. Emotional Suppression.

We are paid to be the stable minds in the midst of unstable souls. We withhold and withhold and withhold and then … then the floodgates open, turning our normally stable personality into a blithering, sobbing mess, or creating a monster of seething anger and rage. During different occasions, I have become both the mess and the monster. The difficulty is only compounded by the fact that you just cannot make your spouse or best friend understand how raising the carotid artery of a nine-month old infant disturbs your mind.

Four. Self-harm.

We cope with alcohol. I know a number who attempt to waste their troubles away with a bottle.

Substance abuse.

Sexual callousness. The sexual philandering that occurred in Six Feet Under was not just for higher TV ratings.

Five. Trivializing.

Compassion fatigue happens to all of us in funeral service. If we can’t bounce back from the fatigue, we begin a journey down the road to callousness. Once calloused, we tell ourselves that “death isn’t as bad as ‘these people’ are making it seem.” Once we trivialize the grief and death we see, we can easily justify charging the hell out of the families we serve.

POSITIVE COPING METHODS

Six. Avoidance.

If this business is wrecking your life and the lives of those around you, then salvage what you have left and quit this business. Quitting doesn’t make you a failure. Quitting doesn’t make you weak. You know more than anyone that you only have one life to life. Live it to its fullest by doing something that breathes life into your soul.

Seven. Altruism.

Learn to love serving others. Probably the best means to cope with the funeral business is found in the people we serve. Love them intentionally and don’t be afraid to find joy in meeting their needs. Don’t be afraid to hear their stories and become apart of their family.

Eight. Problem-solve.

Don’t be passive with the burdens you carry. Actively attempt to find positive ways to deal with your burden. Exercise. Eat better. Take a vacation. Go out with your friends. If you can’t shed your burdens on your own, seek counseling. Find a psychologist. Find a psychiatrist. Talk out your problems with someone wiser than you.

Nine. Spiritual Community and Personal Growth.

Using religion as an opiate to ignore reality is something I speak AGAINST on a regular basis. Instead, seek a community where there’s faith authenticity. Find people who can encourage you with their love and support as you worship together and ponder the mysteries and truths of a better world.

Ten. Benefit-finding.

Emerson said, “When it is darkest men see the stars.” We try our best to deny the darkness of death; we consciously and unconsciously build our immortality projects, hoping that we can live immortally through them.

And then death. Weeping. Our projects come tumbling down. And it’s in those ashes, in the pain, in the grief, through the tears, we see beauty in the darkness. This is a perspective that funeral directors are privy to view on a constant basis. And, in many cases, the darkness can be beautiful.

It’s That Time of Year When Morticians Become Monsters

Funeral directors can crack anytime of the year, but during the winter, it seems our mental state becomes much more vulnerable to suffering from the occupational hazards of burnout, compassion fatigue and depression. Sure, many of us who live in the colder climates of the world suffer through the winter blues; but for those in funeral service, winter often means more sickness, more death and more stress placed upon our shoulders.

Death runs strong before, during and after the holidays … and then somewhere before the start of spring, it seems he pulls a double shift. And as those who follow Death’s movements, we too start pulling the double shifts.

After a month or so of pulling long days, we reach a point and suddenly we feel like we have nothing left to give. So, we push through our exhaustion and it isn’t too long before we morph into stress induced monsters. Yes, monsters.

Death is wild. It has no desire to be tamed. And it’s a capricious boss. It doesn’t follow a schedule. It doesn’t listen to our cries for reprieve. It doesn’t stop when we’re exhausted. We have no control.

And this lack of control is the problem. Since death doesn’t hear our complaints, since it can’t be fought and subdued, we funeral directors will often displace our aggression onto ourselves and our families. And this is where the monster is made.

Pedersen, Gonzales, & Miller write that,

“Displaced aggression is thought to occur when a person who is initially provoked cannot retaliate directly against the source of that provocation and, instead, subsequently aggresses against a seemingly innocent target.”

This “seemingly innocent target” is usually those around us: our spouses, our children, our friends and ourselves.

It’s in these time of burnout that some of us start to drink more heavily; some of us will see our families fall apart before our eyes; and others (like me) will spiral down into deep dark places of depression. Those in the funeral industry can suffer burnout anytime of the year; but during this time of the year particularly, the road can become very difficult.

Often we don’t realize we’re burnt out until it’s too late. We’ve been working so hard trying to stay on top of the funerals we’re arranging that we simply don’t have time to reflect and take stock of our personal lives. Our schedules become so busy that we stop going to the gym, we stop eating healthy, getting enough sleep; and we let our hobbies fall on the wayside.

And out of nowhere our partner leaves us.

Out of nowhere we’re contemplating suicide.

Out of nowhere we’re using a destructive coping mechanism to get through the stress of Death’s spree.

Maybe I’m wrong, but I’ve noticed that the funeral industry doesn’t offer a good support system when it comes to the personal mental and physical health of its workers. When one of us gets burnt out, there’s rarely someone there to council you. Maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t see those in funeral service being encouraged to see out professional help from psychologists.

And maybe it’s time to change that. Maybe it’s time we start recognizing that it happens often in this industry. Maybe it’s time to start doing something about it.

So, if you’re burnt out right now, let me encourage you: seek help. It’s not okay for you to be burnt out. In fact, you’re robbing your family and friends, the people you serve and yourself. You are NOT strong enough to do this on your own. It’s time to overcome the monster.

Battling Burnout: How Funeral Directors Find Peace in the Midst Of Chaos

(This article was originally published in the October issue of The Director. Written for ASD – Answering Service for Directors by Jessica Fowler. Used by permission.

We — at the Wilde Funeral Home — daily use the answering services of ASD; and our customers, no matter how distraught when they call, are always met with a professional and caring voice.)

Funeral Director Thomas Gale counts ceiling tiles. Each one represents another moment in his life to remember not to take for granted. For nearly 20 years, Gale has been a funeral director at Currie Funeral Home in Kilmarnock, VA, and has learned how to balance his professional and personal life after his own brush with mortality.

Gale remembers lying immobile in a hospital bed during a heart procedure several years ago, his only outlet the ceiling tiles above him. When he counts them now, it is to remind him to take regular breaks, set time aside for hobbies and accept assistance from others.

“We take better care of our cars than we take care of ourselves,” Gale says. “If you see a blinking red light in your car, you’re going to pull off the road to get it serviced. Yet, we have warning signs go off in our lives all the time, but we keep driving until we have a major crash.”

A funeral home operates on a constant, 24-hour rotation that never sleeps. On a daily basis, funeral directors must deal with economic, operational and emotional stress, as well as the demands of providing compassion to the bereaved. In Funeral Home Customer Service A-Z: Creating Exceptional Experiences for Today’s Families, author Dr. Alan Wolfelt outlines the symptoms of what he calls “funeral director fatigue syndrome.” Known generally as “compassion fatigue”, this syndrome is common among caregivers who focus solely on others without practicing self-care, leading to destructive behaviors. Some common symptoms include:

*Exhaustion and loss of energy

*Irritability and impatience

*Cynicism and detachment

*Physical complaints and depression

*Isolation from others

While the admirable goal of helping bereaved families may alone seem to justify emotional sacrifices, ultimately we are not helping others effectively when we ignore what we are experiencing within ourselves,” Wolfelt says. “Emotional overload, circumstances surrounding death and caring about the bereaved will unavoidably result in times of funeral director fatigue syndrome.”

Dramatically changing these behavior patterns and adopting positive, healthy habits help these symptoms diminish overtime. While it can be easy for funeral directors to get swept up in the workload, it is often considerably more difficult to allocate free time for leisure. Here are some tips from directors and experts on how to defeat feelings of funeral director burnout:

Family Matters

According to Tim O’Brien, author of A Season for Healing – A Reason for Hope: The Grief & Mourning Guide and Journal, funeral professionals must maintain a near-constant demeanor of strength and self-possession, rarely displaying their emotions.

“Those characteristics are exactly why they need to take time for themselves and practice sound stress management techniques,” O’Brien says. “Yes, they do have to show outward composure and be the steady hand in public. However, they can and should have private time for exploring and expressing emotions. The alternative is often premature death.”

In a recent article for The Director, O’Brien cited irregular hours, interpersonal relationships with employees, limited free time and the often-depressing environment that grief can create as some of the main reasons directors experience compassion fatigue. However, finding a way to strike a balance between professional and personal isn’t as simple for small town funeral homes where the two categories are often one and the same.

Director Stephen Hall grew up in the funeral home business and has worked at the family owned and operated Trefz & Bowser Funeral Home in Hummelstown, PA since he was 12 years old. As an experienced director living in a small town, it is often difficult for Hall to step away from his numerous responsibilities but he has found that the nature of the job offers its own share of rewards as well.

“When my kids were younger, if there was a slow day at the funeral home I was free to attend activities at school because I set my own schedule,” Hall says.

The fine line between personal and professional has always been especially faint for Funeral Director Derek Krentz. He resides at the Gardner Funeral Home in White Salmon, WA with his wife Dominique, also a director, and their children. While Krentz rarely takes vacations, he feels fortunate to work side by side with his wife and still function as a family.

“Its not on common for the kids to do their homework while we’re working. Very often we’re folding memorial folders and laundry at the same time in the middle of the living room floor,” Krentz says. “We rarely go anywhere more than an hour away. You just learn to enjoy being at home.”

Embrace Technological Solutions

In the past, funeral professionals would remain near their firm’s telephone at all times to secure new business and provide families with assistance day or night. Many firms still operate with skeletal staffs, employing only a handful of full-time employees to share the workload. However, in the past decade, new technology and services have emerged that cater to the funeral home industry and help directors conduct business more efficiently.

“With new technology, we’re no longer tethered to a physical location anymore,” Hall says. “Pagers and cell phones have given us the freedom to run our business practically from anywhere.”

Improvements in telecommunications have allowed directors to remain available to families anytime they step out of the office. Whenever Hall has to step out of the office, either for a few minutes or for the evening, he forwards his phone lines to a funeral home exclusive answering service that records detailed messages and contacts Hall for any urgent or first calls.

“When ASD (Answering Service for Directors) came around it was a god send because their people know the profession. All of our calls are screened so we only have to address important concerns right away. ASD can field a lot of the questions that would have been another phone call for me to make,” Hall says. “Now that they have broadened out with the web connection I can log in to see the activity and if there is anything that needs to be addressed immediately.”

Other organizations work to decrease the time consumed by daily tasks at the funeral home. Life insurance assignment companies expedite insurance payments that can otherwise take months for funeral homes to receive. Many funeral professionals rely on removal services to transport decedents after office hours. Software companies have adopted new technology to speed up the process of death certificate filing, obituary placement, and much more.

Yet there is a still a slight stigma associated with modern funeral home practices and some multi-generational and small town firms continue to employ an older business model based on 24/7 availability. Many funeral home owners avoid hiring extra help or seeking assistance from other companies in an effort to provide families with a more personal touch.

“I’m not that computer savvy so I just prefer sitting down with a family while they’re making arrangements and write it down rather than type it into a computer,” Krentz says. “I just find it more personable.”

As President of the Association of Independent Funeral Homes of Virginia and a director in a small, tight-knit community, Gale knows first hand the pressure placed on directors to uphold traditional values. It is the reason why he still sometimes counts the ceiling tiles above his desk—to remember to never ignore his own needs or take his life for granted.

“I remember the old regime of remaining available all the time,” Gale says. “While you still have to be available, you don’t have to do it all alone.”

Care For Yourself So You Can Care For Others

According to O’Brien, funeral professionals are highly likely to develop compassion fatigue without “professional detachment, a positive attitude in the midst of an apparent negative atmosphere, regular personal time and good dietary, sleep and exercise habits.”

Every person needs an outlet: an activity they enjoy that should never feel like work. For funeral professionals, it is essential to seize any opportunity for personal enjoyment, even if only for a few hours.

“I don’t get away a lot but I’ve learned that when things are slow, go fishing, because you don’t know when the phone is going to ring again,” Krentz says.

Like Kretz, Gale is also an avid fisherman and finds the peace and serenity of being out on the water help him restore his state of mind and return to the funeral home with a clearer perspective. He also believes that surrounding yourself with other community members is invaluable to never losing sight of the reason you do your work.

According to Gale, “You’ll become a better person, a better funeral director and just a better over all servant to the people around you if you can care for yourself.”

A change of scenery is also a vital ingredient for maintaining a balanced lifestyle. Apart from the time spent away, physical space acts as a barrier between the mind and the stress agent, in this case, the funeral home office. No one can consistently give 100 percent day in and day out. Regular breaks provide the rest necessary to renew motivation for returning to work.

Last year, Gale took a vacation to spend time with his family in Virginia Beach, VA. For the first time ever, he wanted to free his mind and pretend for one straight week that the funeral home did not exist. At first, the time apart was excruciating. He spent the first 24 hours fighting the urge to check his messages, unable to break decade-old habits of remaining on top of all business, no matter the time or day.

Eventually, he was able to settle in and truly enjoy his break.

“Even the greatest of engines can’t run all of the time without being serviced,” Gale says.

*****

Jessica Fowler is a freelance writer and Public Relations Specialist for ASD – Answering Service for Director where she has answered calls for funeral homes for more than 8 years. Jessica earned her Degree in Journalism from Temple University in Philadelphia, PA and has written articles for The Director, Mortuary Management and American Funeral Director in addition to local travel publications. She can be reached at jess.fowler@myasd.com.

Jessica Fowler is a freelance writer and Public Relations Specialist for ASD – Answering Service for Director where she has answered calls for funeral homes for more than 8 years. Jessica earned her Degree in Journalism from Temple University in Philadelphia, PA and has written articles for The Director, Mortuary Management and American Funeral Director in addition to local travel publications. She can be reached at jess.fowler@myasd.com.

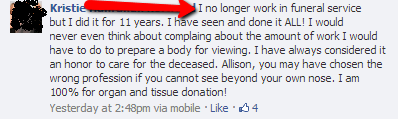

I Don’t Smile When I Embalm Bodies

Earlier this week a contentious discussion brewed on my Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook page. And I’d like to address the topic in my blog’s forum.

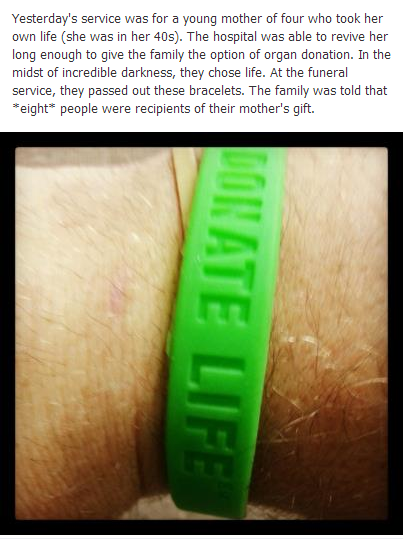

The discussion was kick-started when I posted this status:

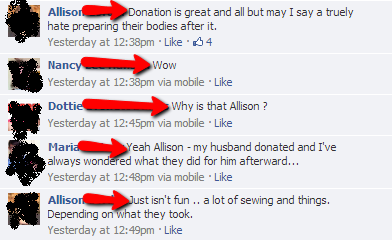

The second comment on the above status was from a fellow embalmer named Allison, who said this:

Allison’s initial comment eventual prompted this comment from a former embalmer named Kristie.

First off, let me say it’s possible for an embalmer to be both 100% for tissue/organ donation and not enjoy the process of preparing a donor. It’s possible for us to be both professionals and human. I’m one such funeral director. I am firmly and unequivocally a supporter of those who choose to find life in a tragic death, and yet when a donor body comes through the morgue door, it’s not Christmas morning.

I know that the best donors are usually young and they usually die from tragic (not necessarily violent) circumstances that leave their body in decent condition to be harvested.

I have immense respect for families who — in the midst of incredible tragedy and darkness — find a way to overcome their pain and chose life by allowing for the harvesting of a body they love so dearly. This act of donation is one of the few genuinely unselfish acts to be found in humanity.

Yet, while I recognize the intense moral beauty and life saving value of organ donation, I’m less than excited to embalm and prepare a donor’s bodies.

Each funeral home and funeral director is different. Some funeral homes are large enough to have shift work; still others are large enough to employ full-time embalmers, who basically embalm body after body all day. Some funeral homes have secretaries, prearrangement directors, at-need directors, full-time pick-up people, etc., etc. But for many of us small firms, we play role of embalmer, secretary, pick-up/livery person, funeral director, at-need director and pre-need director. We’re on call 24/7 and rarely have an uninterrupted holiday.

Our personal lives are not just blurred with our professional lives, they become one and the same, often resulting in sad endings. Divorce. Depression. Burnout.

Our pay doesn’t always justify what this profession takes from us. According to the BLS, the average embalmer makes $45,060, which isn’t bad until you consider that the salary often comes at the expense of our souls. I’ve worked 20 hour days. I’ve worked 100 hour weeks. Most months I get two days off. This month, my weekend off happens to be this weekend and with the snow coming, I may have to work the plow on one of my “days off.” And when I am home, it’s hard to get comfortable as I’m one phone call away from going back to work.

I was up until 12 midnight writing this post and then at 3:30 AM I was called into work. I won’t be finished work until roughly 5:30 PM.

Here’s a picture of me at the nursing home at 4:40 this morning. The smile is real … the nurses were making fun of me for taking the photo.

And although this isn’t about me and the burdens I carry, I will say that my experience isn’t exceptional. The at-need demand, emotional and long hours take their toll on us as people.

So, when the heart is donated and I have to raise six arteries instead of one, I don’t smile.

When there’s bone donation, I don’t look forward to moving the Styrofoam rods around to make the appendages look natural.

When skin is grafted, I don’t smile when I’m cleaning the seepage off the floor.

When I get various liquids on myself because of the intrinsic messy nature of donor bodies, my face doesn’t crack a grin.

Unless I’m listening to stand-up comedy on the morgue’s radio, I don’t embalm bodies with a smile.

I appreciate Kristie’s assertion that she has never thought about complaining when preparing a body. And I appreciate that she always sees it as an honor. I will be the first to admit that Kristie is probably a better person and funeral director than I am. Maybe her suggestion to Allison (that Allison should find another profession) applies to me as well.

But, I, in contrast to Kristie, think it does us funeral directors well to be honest. Maybe not in a public forum like I’m doing now, but we need to recognize that we’re both professionals and human. We love to serve you, but there’s times when we too need to be helped. We need to fight that perception that to be a professional means being an unfeeling robot. We need to ask for help, sometimes we need to seek counselling. If you’re a funeral director and you don’t embalm donor bodies with a smile, it’s okay.