Dying Well

Let’s Talk about Brittany Maynard

Despite all the negativity and divisiveness I’ve witnessed on social media concerning Brittany Maynard’s decision, I can’t help but think that she’s performed a modern day miracle: She’s enabled a large scale death conversation. She’s enabled us to think about end-of-life decisions. And hopefully, she’s inspired us to think about our own mortality.

Like with anything powerful, there’s always the danger of it being abused. And this conversation – the conversation about Brittany’s choice – is incredibly powerful. The abuse of the conversation looks like this: judgment towards Brittany Maynard. Let’s be clear. Brittany Maynard is dead. No amount of judgment will bring her back or reverse her decision.

You can disagree with her decision. That’s fine. In fact, that’s the point. The point is NOT for you sit by and ignore the Brittany Maynard conversation with formulaic clichés; the point is for you to deal with these thoughts internally … to let them settle into your being and find a home. The point is for you to think about how you want to die and what you would do if you found out that you were terminal. You’ll kill this very valuable conversation by getting stuck in judgment instead of asking yourself some very important questions.

Her death, whether you agree with it or not, has provided you with an opportunity to grab ahold of the end-of-life conversation, and help create a future for yourself where you know what YOU want.

Do you want palliative care?

Hospice care is a fantastic way of bringing terminally ill patients home while simultaneously relieving their physical and emotional pain through various forms of care. Is that something you want?

Do you want “death with dignity” laws in your state?

As of today, only Oregon, Washington and Vermont have “death with dignity” laws. If this is something you’re pro or against, it’s time to start voicing your opinion; and make sure you have legitimate reasons behind your opinion.

Have you thought about a living will?

Do you want to die with tubes hooked into your body, being sustained indefinitely by machines while your unconscious body lives on in a semi vegetative state? I don’t. And I’ve made it clear that I don’t. If you want the cyborg death and you don’t want anyone “pulling the plugs”, that’s fine … but either way you should probably make it official by creating a LIVING WILL.

At what point will you say, “I’m done with the medical ‘miracles’ and I’m ready to die”?

Perhaps one day you’ll be under dialysis, or have cancer that “might” be able to be fought through an undetermined amount of chemotherapy. How much are willing to tolerate? At what point are you ready to say, “enough is enough”?

If we look to answer these questions and refrain from judging Brittany’s very personal decision, value will come from Brittany’s death … and not more divisiveness. Because, according to Gallop, this issue IS the most divisive issue in America. It’s more divisive than abortion. It’s more divisive than LGBTQ rights.

And this is the reason it’s so divisive: we’ve given such little thought to end-of-life decisions that when we talk about “death with dignity” our reactions are almost entirely emotional. We react entirely out of anger, or compassion and we have little to say in the vein of reason. We talk about “slippery slope” or we use the “God argument” or we harken back to how we put down our dog when the dog couldn’t walk anymore (which really isn’t helpful to compare people to animals).

As I — and many others — have said, most Americans obsessively attempt to deny their own mortality. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross writes in “Death: The Final Stage”:

Dying is an integral part of life, as natural and predictable as being born. But whereas birth is cause for celebration, death has become a dreaded and unspeakable issue to be avoided by every means possible in our modern society. … It is difficult to accept death in this society because it is unfamiliar. In spite of the fact that it happens all the time, we never see it. When a person dies in a hospital, he is quickly whisked away; a magical disappearing act does away with the evidence before it could upset anyone. … But if we can learn to view death from a different perspective, to reintroduce it into our lives so that it comes not as a dreaded stranger but as an expected companion to our life, then we can also learn to live our lives with meaning— with full appreciation of our finiteness, of the limits on our time here.

Where does the end-of-life conversation go from here … after Brittany Maynard? I don’t know. Nobody knows. Because the conversation is partially up to you and me. Do we let the conversation die in judgment and emotions? Or do we take the stage that Brittany’s death created and talk about something we rarely talk about? Can we learn to make death the “expected companion”? I hope we take the stage. I hope we share. I hope we embrace mortality and the life that comes with it.

11 Reasons You Need to Think about Your Death RIGHT NOW

One. Paul Blart.

Two weeks ago we had a family that was verbally fighting over “what mom wants” for her funeral. The fighting got so intense that one side actually brought a security guard with them to the funeral.

Don’t have Paul Blart security guards at your funeral. Determine what you want at your funeral now so your family doesn’t fight over it later.

Two. The Cyborg Death.

Thinking about your death now, also makes us think about how we die. Do you want to die with tubes hooked into your body, being sustained indefinitely by machines while your body lives on in a semi vegetative state? I don’t. And I’ve made it clear that I don’t. If you want the cyborg death and you don’t want anyone “pulling the plugs”, that’s fine … but either way you should probably make it official by creating a LIVING WILL.

Three. Breast Augmentation.

That legal document (called “a will” or “testament”) that makes sure your stuff doesn’t somehow end up funding your ex-husband’s new trophy wife’s breast augmentation is important to do BEFORE you die.

Four. Your debts don’t pay off themselves.

And if all the stuff you have is debt and darkness and you don’t want to leave your parents paying for your college or your children paying for your house, you may want to think about term life insurance. Unlike General Motors, you don’t receive a bailout when you die.

Five. Because you don’t know the difference between an executor and a power of attorney.

Six. The Stupid Tax.

Because the less you think about death (your own death and the death of your loved ones), the more likely you’ll be hit hard with the stupid tax.

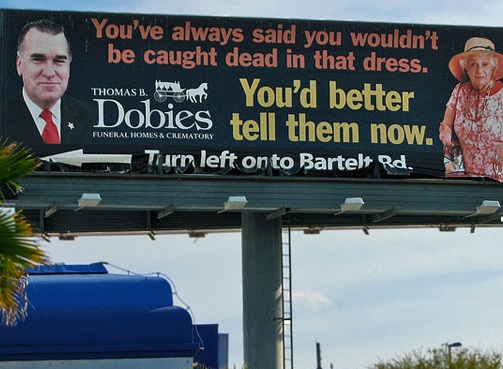

The stupid tax applies to funerals: Did you know that if you can save money by planning for a natural burial and/or a home funeral?

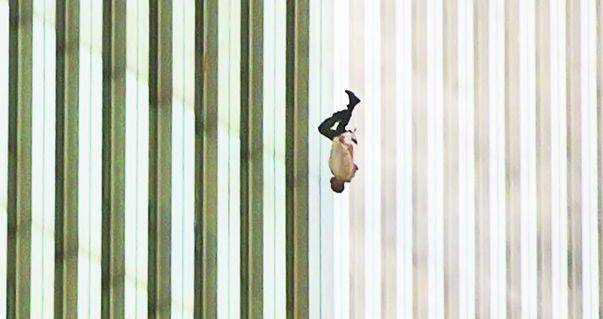

Seven. This.

Eight. You Can Be a neo-Zombie.

One organ donor can save up to eight lives. So, be an organ donor and pieces of you will be walking around long after you’re gone. You’ll be like a Zombie, but a living one … which is cooler. It’s like a neo-Zombie.

Nine. Fido Doesn’t Want to be Euthanized

You have godparents for your kids. But do you have godparents for your pets? Make sure someone is there to take care of your animals because if no one steps up they could go to the rescue. And while nobody at the rescue wants to euthanize Fido, sometimes it has to happen.

Ten. Dying Makes You Drunk

I know. You’re not dying right now. And Death probably isn’t scheduled into your calendar anytime soon. But you think, “I’ll probably die of cancer at an older age and then I’ll get my house in order. I’ll write my will, I’ll determine my Living Will, I’ll name my power of attorney and executor, I’ll make my prearrangements for my funeral, etc. etc.”

There’s a slight problem with that line of thinking. Dying kind of makes you drunk. Not drunk in the “let’s have a good time” sense, but drunk in the “I really shouldn’t be making big decisions right now” sense. Dying often changes us. And it often prompts us to make less than objective decisions.

So, if you want to leave all those big decisions up to drunk you, go ahead. Just let me know, so I can take your money. Bwhahahaha.

Eleven. Life.

Because the more you think about death, the more you realize that all of this has an end. And the more you realize that you, your parents, you friends and your family will eventually die, the more you can embrace this precious thing called life.

By embracing death, we embrace life.