Disposition

Alkaline Hydrolysis: Water Cremation and the “Ick Factor”

By Traci Rylands

Today’s guest post is a little graphic in describing how cremation works.

I recently wrote about the history of cremation in America and how it’s becoming more popular every year. However, an alternative form of cremation is gaining attention that’s truly different. Resomation, bio-cremation and flameless cremation are a few of the buzzwords used, but the scientific name for the procedure is alkaline hydrolysis (AH).

So how do you cremate a body without a fire?

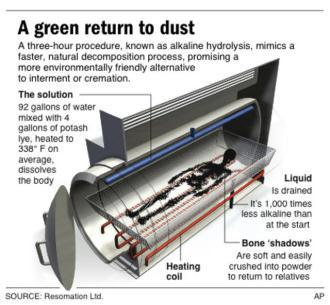

This graphic from Resomation, Ltd. explains the alkaline hydrolysis process. The company was founded in 2007 in Glasgow, Scotland by Sandy Sullivan. Ironically, AH is still not legal in the U.K. at this time.

Alkaline hydrolysis is a water-based chemical resolving process using strong alkali in water at temperatures of up to 350F (180C), which quickly reduces the body to bone fragments. Experts say it’s basically a very accelerated version of natural decomposition that occurs to the body over many years after it is buried in the soil.

AH was originally developed in Europe in the 1990s as a method of disposing of cows infected with mad cow disease. In England, AH for humans is not fully legalized yet. It’s usually referred to as resomation there because the commercial process was first introduced and trademarked by Resomation, Ltd. They received the Jupiter Big Idea Award (from actor Colin Firth, no less) at the 2010 Observer Ethical Awards.

Yes, that’s Colin Firth (aka Mr. Darcy) on the end. He presented the Jupiter Big Idea Award to Resomation, Ltd. at the 2010 The Observer Ethical Awards. The firm’s founder, Sandy Sullivan, is standing to his left. Photo courtesy of The Observer.

The University of Florida and the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota already use AH to dispose of cadavers. It’s not surprising that both states were among the first to legalize its use. The other states are Colorado, Oregon, Illinois, Kansas, Maine and Maryland.

But why would someone want to do what amounts to liquifying the body with lye instead of traditional cremation? Some people worry about the carbon footprint left behind by traditional cremation. AH is supposed to remove that problem.

In the traditional process that uses fire, cremating one corpse requires two to three hours and more than 1,800 degrees of heat. That’s enough energy to release 573 lbs. of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, according to environmental analysts. In many cases, dental compounds such as fillings also go up in smoke, sending mercury vapors into the air unless the crematorium has a chimney filter.

During AH, a body is placed in a steel chamber along with a mixture of water and potassium hydroxide. Air pressure inside the vessel is increased to about 145 pounds per square inch, and the temperature is raised to about 355F. After two to three hours, the corpse is reduced to bones that are then crushed into a fine, white powder. That dust can be scattered by families or placed in an urn. Dental fillings are separated out for safe disposal.

Anthony A. Lombardi, division manager for Matthews Cremation, demonstrates a bio-cremation (AH) machine. Photo courtesy of Ricardo Ramirez Buxeda/The Orlando Sentinel.

AH is purported to use about one-seventh of the energy required for traditional cremation. Some studies indicate that AH could save 30-million board feet of hardwood each year from cremation coffins. That’s very attractive to some people. However, one question remains. What happens to what’s leftover from the process (besides the ashes)?

That’s when the “Ick Factor” comes in.

Leftover liquids – including acids and soaps from body fat – plus the added water and chemicals, are disposed of through a waste water treatment process, according to John Ross, executive director of the Cremation Association of North America.

In other words, it goes down the drain like everything else.

“It’s very similar to the treatment of excess water from any (industrial) facility. In fact, it probably has less of a chemical signature than would you find (in liquids) coming out of most (industrial) plants,” Ross said.

Ryan Cattoni, funeral director at AquaGreen Dispositions LLC, offers the first “flameless cremation” in Illinois. Photo courtesy of Brian Jackson/The Sun-Times.

Still, the visual picture that creates is not very attractive. In fact, a 2008 article about AH said the thick coffee-colored liquid left behind resembles motor oil and has a strong ammonia smell. Not exactly something you want to put on a colorful marketing brochure.

AH became legal in Colorado in 2011. Steffani Blackstone, executive director of the Colorado Funeral Directors Association, spoke frankly about the “Ick Factor” when legislation to approve AH was being crafted.

“People seem to have objections when they actually think about that too long. They ask: ‘Well what happens? Does (the body) turn to sludge?’ And the thought of grandma being sludge is kind of disgusting to them.”

While currently legal in only eight states, the movement to make it so in others is real. In New York, the legislation became known as “Hannibal Lechter’s Bill.” New Hampshire legalized AH in 2006 but banned it a year later. In Ohio, the Catholic Church is a vocal opponent to AH and it has yet to be fully approved there.

Jeff Edwards, an Ohio funeral director who performed several AH procedures before being told to stop, filed a lawsuit in March 2011 against the Ohio Department of Health and the Ohio Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors after ODH quit issuing permits for AH body disposals. A judge ruled that ODH and the board had the authority to determine what is an acceptable form of disposition of a human body, as set forth in the Ohio Revised Code.

The cost of an AH machine can range from $200,000 to $400,000, depending on its size and capacity. That hefty price tag did not stop Anderson-McQueen Funeral Home in St. Petersburg, Fla., from becoming the first in the state to purchase one to provide AH to their clients. They refer to AH as “flameless cremation”.

Funeral home president and owner John McQueen said in a 2011 article that he planned to charge clients the same prices for AH cremations as the traditional ones, which can cost from $1,000 to $2,000.

Anderson McQueen became the first funeral home in Florida to offer alkaline hydrolysis to its clients. They call it “flameless cremation”.

So what do I think? In the end, traditional cremation sends its byproducts up into the air. AH sends them into the water for treatment. Which is better for the environment? I don’t know. I’m not fond of the idea of being burned up or liquified, especially the latter. The “Ick Factor” does give me pause.

A pine box in the cemetery still sounds better to me.

*****

Todays’ guest post is written by Traci Rylands of Atlanta, Ga. Traci writes, “I’m a photo volunteer for Findagrave.com, a database of cemeteries around the world. I enjoy learning about the stories of those individuals whose graves I find while educating others about death and dying.”

Please visit Traci’s blog, “Adventures in Cemetery Hopping.”

You can also like her blog on Facebook. And follow her on Twitter.

More Room for Me . . . at the Cemetery

Today’s guest post is written by Ed Munger:

*****

It’s always a fitting time to consider what kind of environmental destruction I’ll leave in my wake once I depart.

Others, I’m afraid to say, are more concerned with their environmental footprint – or body print – than I am. For them, there’s a veritable cornucopia of options for final remains, aside from traditional cemetery burial.

Some offer the option of leaving a real statement that says “hey, this guy really cared about the planet.”

Some of the natural and green burial movements aren’t a major departure from tradition, but these options do seek to reduce the human impact after death.

Cemeteries are gradually opening up spaces dedicated to environmentalists – some go so far as to offer wildflower meadows devoid of headstones and markers.

These options further reduce environmental impact by eliminating all the mowing of grass and weed-whacking that makes use of fossil fuels. It’s one of the less-extreme measures that’s taking root on the American burial scene.

More-extreme to me is this mushroom death suit I’ve been reading about. According to the Infinity Project, studies and tests are underway to develop the perfect mushroom that would “consume” what’s left of a person.

A prototype of the suit isn’t too pretty, the one I saw was black in color and looked like something you’d wear on a deep ocean dive (see below).

But it’s supposedly filled with mushroom spores which, once I started going sour, would consume all that’s left of me including all the mercury I’ve collected from eating fish I caught.

I’ll have to assume these mushrooms are not edible. I hope they place a sign or something near them so people who pick berries and wild fruit don’t accidentally make soup out of them.

I’m unsure if there’s a quiet disagreement underway between the green burial clan and the cremation club. Cremation doesn’t leave much but ash – yet it requires combustion and ultimately puts ‘people smoke’ up into the air.

I’m not going to look it up. I’m sure somebody out there has detailed all the byproducts of people combustion.

For those willing to accept a little smokestack pollution, there’s a big list of otherwise nature-friendly options for final remains.

Scattering is one of the more-senior of these options. Mariners are providing the service, offering people a chance to have their remains scattered into the ocean.

That’s a viable option for those who love the sea.

So too is the idea of incorporating a person’s cremated remains into an appropriate shape for a reef – offering tiny sea creatures a new home with a human touch.

In terms of reducing the impact my dirty remains will have on the Earth, being cremated then sent into outer space seems like an option worth looking into.

There’s a company that will send a “symbolic portion” of cremains out into space on a commercial flight that’s heading up anyway to bring a satellite into orbit.

The company, Celstis, boasts responsibility for the first human burial on the moon back in 1999.

I’m not sure if I’m happy about this idea. I haven’t decided yet if I want to create an environmental movement dedicated to the moon, plus I’m still thinking about pitching a new idea to situate a landfill up there, so I’m a bit conflicted.

It might be a stretch to get tradition-minded people to consider having their remains cast off the planet, but that doesn’t make these people anti-environment either.

The next best thing for the terrestrial environmental burial also involves cremation ashes – placed into the Bio Urn.

These types of final resting places entail putting people’s ashes into a biodegradable cup filled with a seed so that the deceased will be engrained into a tree that grows and reaches towards the sky.

Trees produce oxygen too, so it’s a way of giving back some of the air we selfish humans think nothing of breathing in all the time.

It seems to me new methods of dealing with our final remains just keep surfacing, which is a great thing in terms of giving people options.

It’s even better for me – I consider myself among the most selfish people on my planet.

It’s no secret people are opting for cremation at increasing rates, reducing what’s left of themselves to a bucketful of ash.

Whether these remains are stored in a columbarium or scattered over the desert, ocean, or tossed on a shelf, they are taking up much less space than we, as a people, used to in the old days.

Picking up candy bar wrappers when I’m out in the woods hunting probably doesn’t get me into the environmentalist club.

Nor does keeping the heat on at 70-degrees in my house when it’s chilly.

And I need four-wheel-drive, living in Upstate New York, which requires a bit more fuel. I mow my lawn with a gas-powered mower and have no problem letting machinery do the work when there is a machine to do it.

I consider that an expression of my pride in the accomplishments of industrious, inventive people.

For a stodgy and uninteresting person like myself, all these new-age and environmentally-friendly burial methods are a source of happiness.

But that’s not because I have any intention of taking advantage of them.

I tried to envision myself as a coral reef but can’t get the thought of my old fish tank – and what the fish did to the pretend reefs I put on the bottom – out of my head.

I am equally uninterested in having a bunch of fungi feed off of my hide.

Ultimately, I plan to get the whole nine yards of a funeral just like my grandfather and his grandfather and the rest of my family.

I’ll be taking up a slew of space underground and bringing all my chemicals with me, along with my stamp collection.

So the continued movement towards Earth-friendly final remains disposition is a good thing for me.

It means it’s less-likely I’ll be told there’s no room for me in the cemetery.

*****

Ed Munger oversees social media and assists with communications for the New York State Funeral Directors Association. Ed was previously a newspaper reporter, winning several prestigious awards from the NYS Associated Press Association. Ed is the main contributor for the blog Sympathy Notes, at http://www.sympathynotes.org/Follow him on Twitter @SympathyNotes

My Visit to a Green Cemetery

There are only a few green cemeteries in the Eastern part of Pennsylvania, none of which are close to my funeral home’s location. Based solely on the information on their website, I decided to visit “Green Meadow” Cemetery some two hours away in Lehigh Valley. I called the “contact” number and soon heard a woman’s pleasant voice on the other end. “Hello”, she said cheerfully. As much as I was pleased to find such cheerfulness, I was also somewhat confused as I expected her to say, “Hello. Green Meadow Cemetery.” It seemed as though I had called someone’s home telephone number. I started, “Hi. My name is Caleb. Is Ed available?” “One minute”, she replied. Ed – the name attached to the website’s contact number — grabbed the phone and we chatted for 15 minutes about Green Meadow and the philosophy behind it. I explained that I was writing a small paper on green cemeteries for my post-grad class and we set a date for me to come up to Green Meadow and take a tour.

I arrived on time to find Ed already waiting. He was a young man in his seventies. I say “young” because it seemed Green Meadow was an inspiration for him that brought out the energy of youth. He explained that twelve years ago the Fountain Hill Cemetery (founded in 1872) had exhausted its perpetual care funding and – like many cemeteries – was on the brink of death.

The cemetery was unassociated with a church or organization and was simply a non-profit with no owner or director. Ed and a few others took it upon themselves to revive the dying cemetery and after 12 years of volunteer work the cemetery was just starting to stand on its own. Part of the revival of the old cemetery has been the inclusion of Green Meadow, which sits within the boundaries of Fountain Hill Cemetery on a half-acre of wildflowers, grasses and shrubs.

Through a mutual friend, Ed was introduced to Mark Harris, the author of a Green Burial standard entitled “Grave Matters: A Journey through the Modern Funeral Industry to a Way of Natural Burial.” After numerous conversations, Ed and the board at Fountain Hill partnered with Mark to create a philosophically sound green cemetery some four years ago. Ed said that “Mark remains the cemetery’s greatest proponent.” Mark writes in his book, “The modern funeral has become so entrenched, so routinized, in fact, that most families believe it’s all but required when death comes calling (Harris 2007; 47). Green Meadow cemetery calls into question the “all but required” traditional American funeral.

On a larger front, the green burial movement is interrelated with the natural death movement, home funerals and the natural birth movement as it underscores the desire to move away from the Promethean attempts of industrialized science and technology (Verhey 2011; 32 – 33). Paula Hendrick, who surveyed the natural death movement in America notes that “our focus on personal autonomy and self-development have made it very hard for us to accept the inevitability of death” (Albery and Wienrich 2000; 11). Michael Ignatieff writing for “The New Republic” echoes Hendrick when he states, “’Cultures that live by the values of self-realisation and self-mastery are not especially good at dying, at submitting to those experiences where freedom ends and biological fate begins. Why should they be? Their strong side is Promethean ambition: the defiance and transcendence of fate, the material and social limit. Their weak side is submitting to the inevitable” (Albery and Wienrich 2000; 12).

Indeed, buried beneath a full ten-acre American cemetery is enough wood to build forty houses, twenty thousand tons of concrete from the vaults, over nine-hundred tons of casket steel, and enough embalming fluid to fill a small swimming pool (Harris 2007; 38). The idea of natural burial accepts the inevitable that despite concrete, wood, steel, preservative agents and the idealized attempt at physical immortality, the body will eventually decompose back to dust. Natural burial will, per Mark Harris,

allow and even invite, the decay of one’s physical body … and return what remains to the very elements it sprang from, as directly and simply as possible. In their last, final act, the deceased … have taken care in death to give back to the earth some very small measure of the vast resources they drew from it in life, and in the process, perpetuate the cycles of nature, of growth and decay, of death and rebirth, that sustain all of us. (Harris 2007; 42).

Mark’s ideas are the heart behind the little cemetery “Green Meadows”, a place where one can “degrade naturally and rejoin the elements, to use what’s left of a life to regenerate new life, to return dust to dust” (http://www.greenmeadowpa.org/about-us/). As Ed and I walked through the snow covered cemetery – stamped with the snow tracks of deer and birds — Ed pointed out the various graves. He noted that the first prominent burial in Green Meadow spurred some media attention. Patrick B. Ytsma, a well known local bicyclist, was struck and killed while riding his bicycle. His decision to be buried in Green Meadow inspired a newspaper article featuring the cemetery as well as the donation of labor and supplies for the erection of the cemetery’s sign.

And yet despite Mark’s advocacy and the attention that Ytsma’s burial gained, the demand for green burial in the Lehigh Valley remains small with only an average of two burials per year. Ed – a generation ahead of his time – anticipates that the young generation that have been inspired by the larger green movement will slowly but surely begin to fill the beautiful little natural hillside that is Green Meadow. This, in many respects, is Ed’s heritage to the next generation and gift to a brighter, greener future.

Ten Things About Embalming

One. It’s weird.

Yes, we lay a nekked person on a table and take out their blood, replacing said blood with embalming fluid. Weird? Yes.

But so is cremation, sky burial, endocannibalism, famadihana and mummification.

Two. It does not preserve the body indefinitely.

You can’t dig up an embalmed body from 1920 and expect it to be a perfect specimen of unblemished human anatomy. It’s possible that the body is in good shape, but not probable.

The official definition from the American Board of Funeral Service Education states that embalming is “the process of chemically treating the dead human body to reduce the presence and growth of microorganisms, to retard organic decomposition, and to restore an acceptable physical appearance.”

Reduce, retard and restore. Mainly the restore part.

So … about Vladimir Lenin and his dead-since-1924 body that is still viewable today? Harry Potter magic and a few other tricks is the answer.

Three. In most states, what is pushed out of the body goes down the drain and out into public sewage.

Now you know.

Four. Embalming doesn’t promote the public health.

There’s an idea (possibly perpetuated by societal laws, originating back to Mosaic Law and certified in pandemics like “The Plague”) that you can catch death by hanging around a dead body.

For the most part, it’s just not true. They’re safe. Sure, you shouldn’t want to be all buddy-buddy with a dead body, but an unembalmed body won’t kill you. Dead bodies aren’t zombies

Five. It guarantees you won’t be buried alive.

If you fear getting cremated alive or buried alive, embalming guarantees neither of those things will happen. But if you live in a “First World” country, you don’t have to worry about getting buried or cremated alive. We’re pretty good at determining death. For the most part.

Six. It helps make the symbol of death look pretty.

The dead body is the symbol and it’s a symbol that needs to be seen. It needs to be seen for reasons of grief work and for death denial confrontation. Dr. Erich Lindemann (grief management pioneer) says that a defining characteristic of persons dealing with complicated bereavement is that they never saw the dead body of their loved one.

An embalmed body helps the symbol look good. There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s a good thing. In fact, at times it’s a beautiful thing.

Certainly, embalming isn’t necessary AT ALL to see the dead body. But, it can help.

Seven. Embalming fluid is not environmentally friendly.

The most environmentally friendly form of burial is a natural burial. Plain and simple. Cremation isn’t wonderful for the atmosphere. And embalming fluid isn’t wonderful for the ground.

Eight. Embalming isn’t the “Traditional Funeral”.

We didn’t do the whole arterial embalming thing until the mid-1800s. Before that it was all natural and dirt and fire and other things. The “traditional funeral” is actually rather non-traditional when you consider the sum history of Homo sapiens.

Nine. It is rarely required.

If you’re getting cremated, it’s OBVIOUSLY not required. For viewings and burials, local laws differ on embalming requirements (some areas require a body to be embalmed if it isn’t buried after it’s been dead for 10 days). Alabama, Alaska, and New Jersey require embalming if you’re transporting a body to their state (which is a stupid law). Various types of refrigeration are an alternative form of temporary preservation while awaiting a funeral service and/or viewing.

Ten: Embalming fluid shouldn’t be smoked.

Seriously. Don’t smoke wet. Embalming fluid is meant for dead people.

Home Funerals, What are they?

It’s strange how professional practices can reverse themselves.

Traditionally, in America, funerals have been held in the “parlour” of the deceased’s home. During the beginning decades of the twentieth century, the funeral business became more industrialized and funerals were moved to what we now call “Funeral Homes”, or “Funeral parlours.” Recently, however, there seems to be an interesting trending back toward “home funerals.”

This could be related to an evolution in understanding what the funeral is meant to accomplish for the grieving family. Having a funeral at a funeral home allows the director to take care of things for the family, but it also, by default, creates a disconnect between the funeral arrangements and their naturally occurring emotions.

In actuality, it causes a temporary shut-down of the grieving process for the length of time between the initial meeting with the funeral director and the post-reception gathering. This is not a bad thing—just the way it works.

On the other hand, with “home funerals,” the grieving process is allowed to progress uninterrupted. There is no unfamiliar setting for the funeral, no feeling that one has to put on a brave face in public. The family and friends are in their loved one’s home (or that of a close relative or friend), surrounded by familiar objects and memories. This fosters a feeling of security, so that it is safe to cry because everyone else understands, okay to laugh at funny memories, all right just to sit and take your time dealing with the loss. All this happens while the funeral director patiently talks the family through their tough decisions in the comfort of their own family room or at the kitchen table. The funeral director may even share meals and quiet time with the family. The developing familiarity and friendship prepares them to feel more comfortable during the funeral service itself.

Another benefit of home funerals is that schedules are much more relaxed for everyone. Home funerals are actually a two or three day experience, because many of the preparatory tasks ordinarily handled at the funeral home are done at the family’s home; the funeral director simply drops by the house when matters need to be tended to. Grieving cannot be rushed, so this new type of funeral offers a more personalized approach. Unlike funeral parlors which close at a set hour, with “home funerals,” people can sit with the deceased all night if they want or need to. No one will tell them that they have to leave.

Home funerals meet the needs of a growing percentage of grieving families. They are obviously not practical for large gatherings, so they will probably never become the norm—but it is comforting to know that they are an option.

****

Today’s guest post comes the hard working, creative entrepreneur, Matthew White. Matthew graduated from Cambridge in 2002 majoring in English after which he traveled Central America, Australia and South East Asia. While abroad he gained an abundance of cultural experience and also taught English in various places. He worked for Life Trends Magazine as the creative director from 2008-2009.

Since then, he has been working on developing resources to help grieving families, which resulted in opening the website funeralparlour.com which currently specializes in obituary templates and their complete customizations. He plans on broadening the scope of this website in the near future. Give him your “like” on his Facebook page.