Caleb Wilde

(218 comments, 980 posts)

Posts by Caleb Wilde

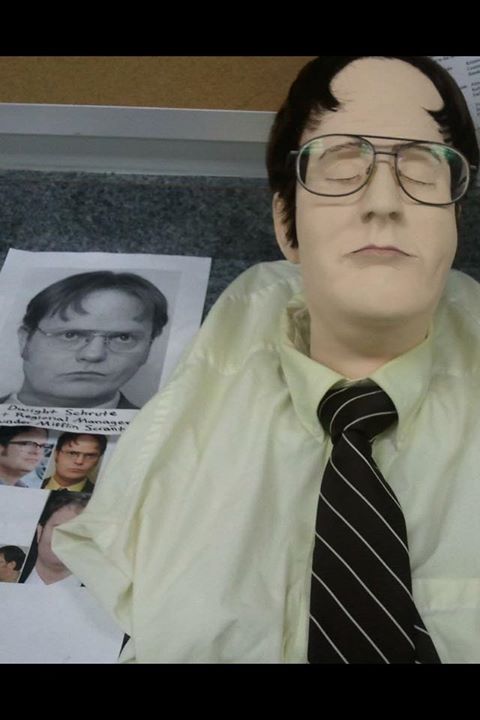

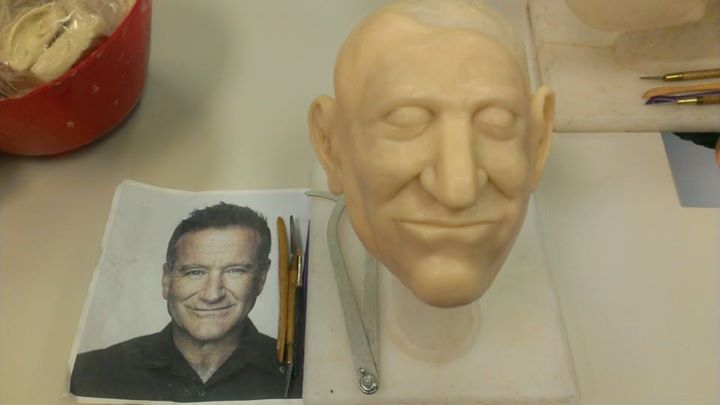

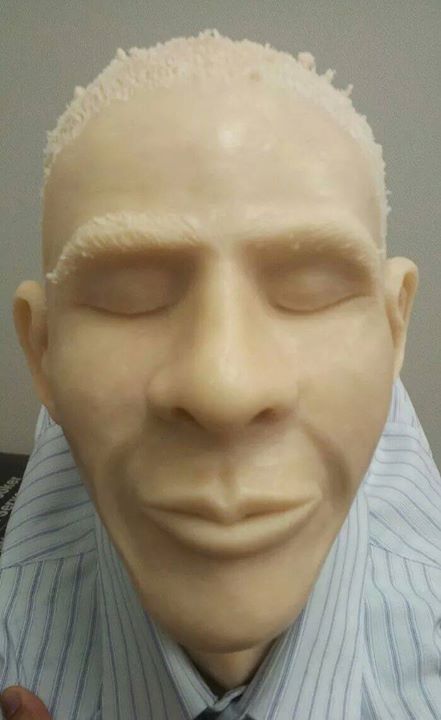

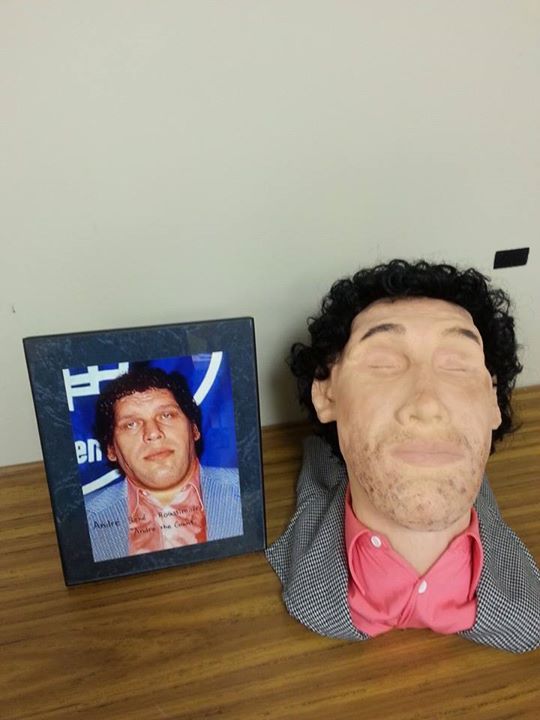

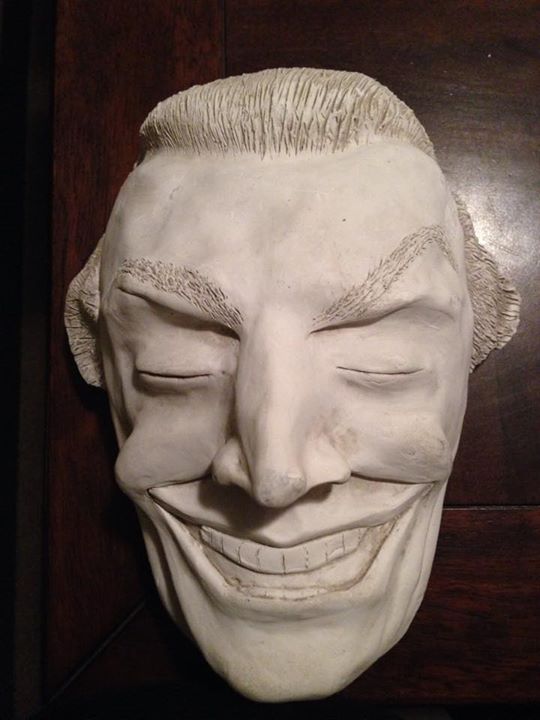

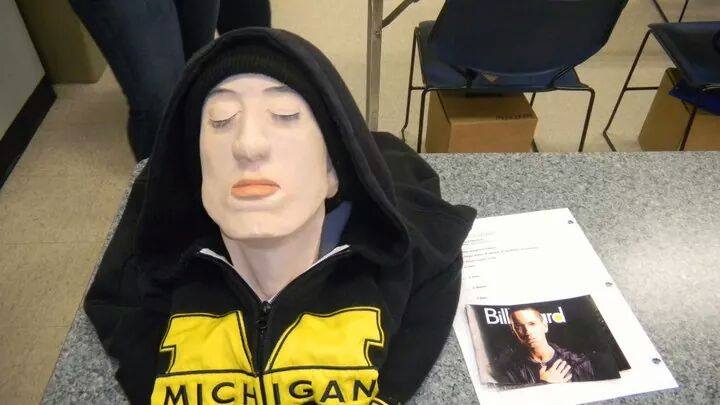

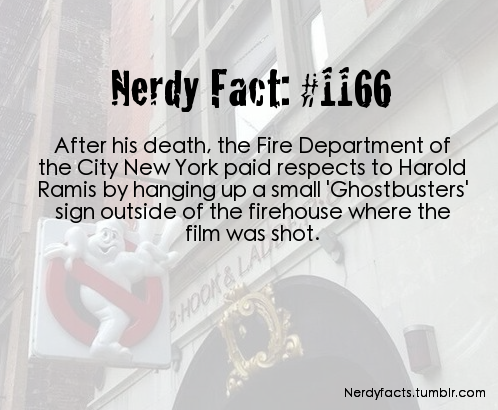

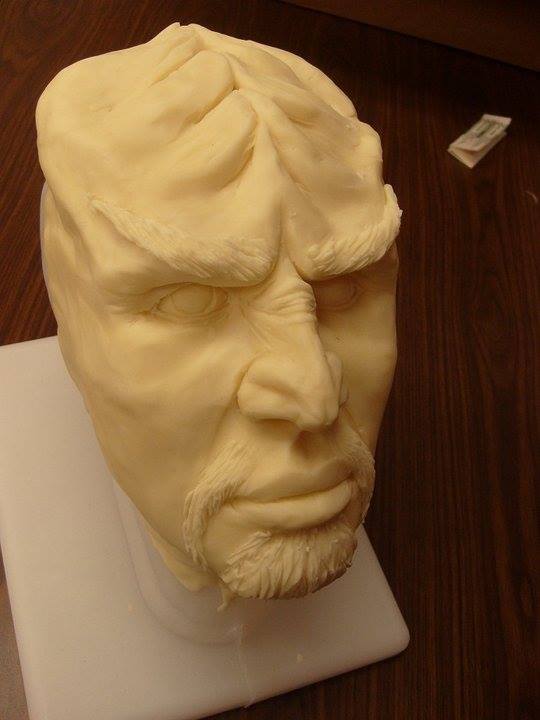

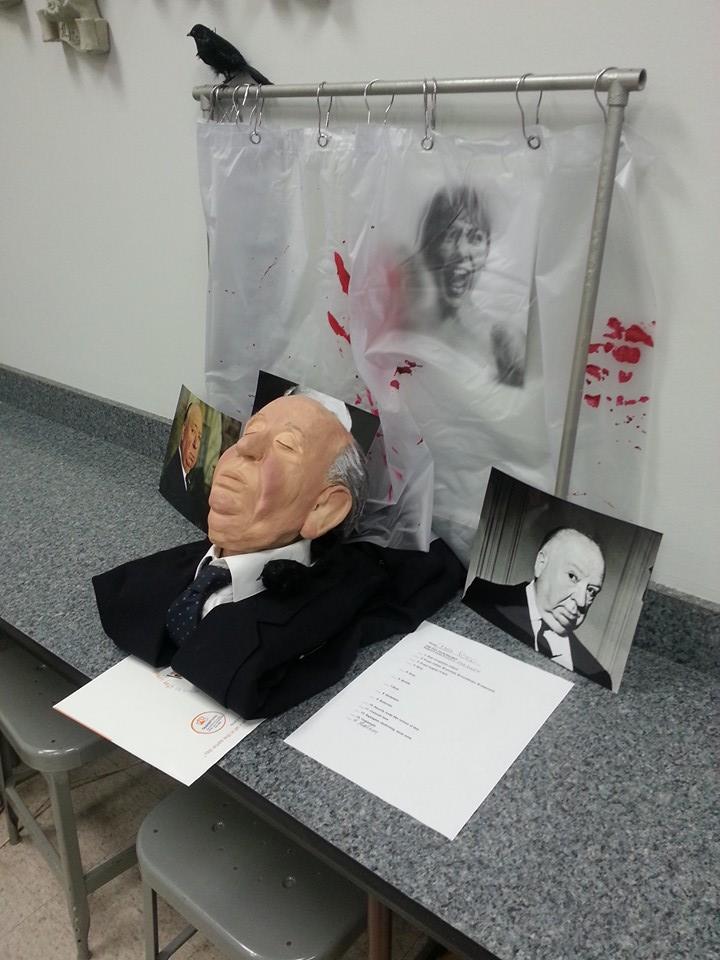

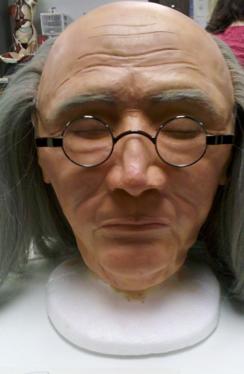

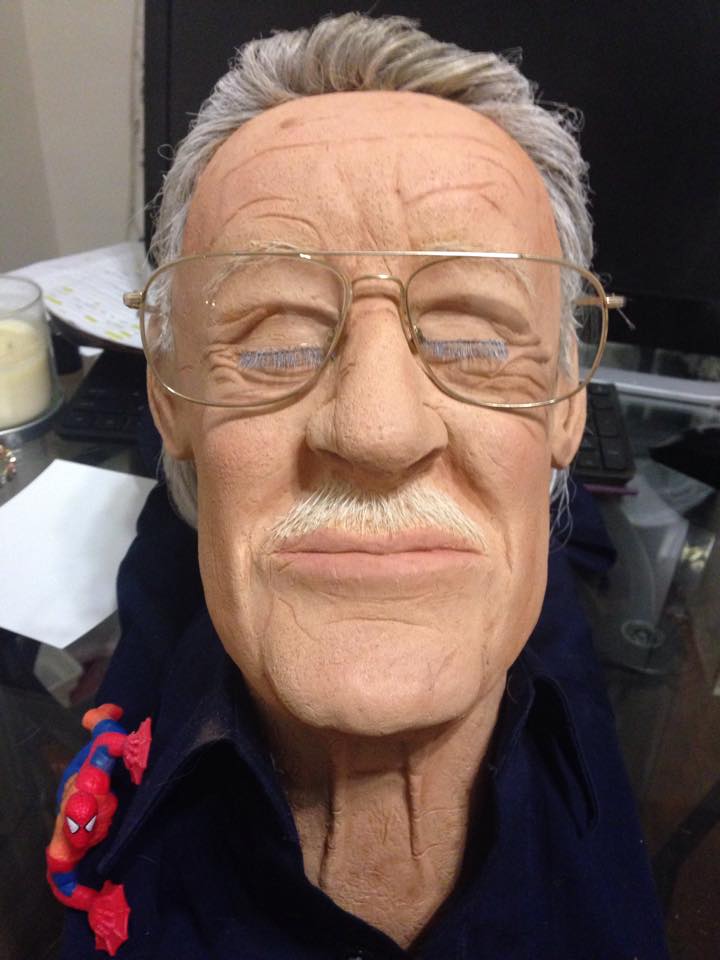

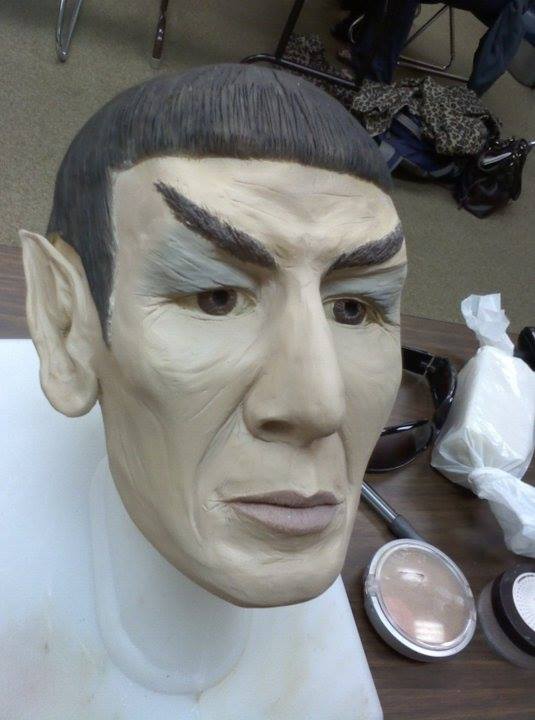

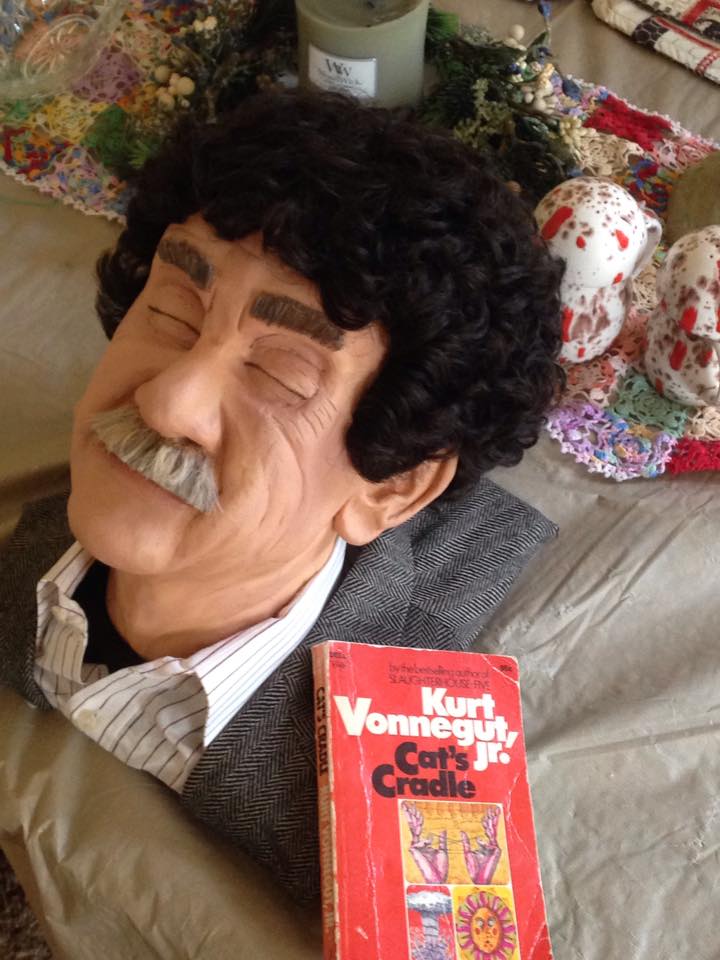

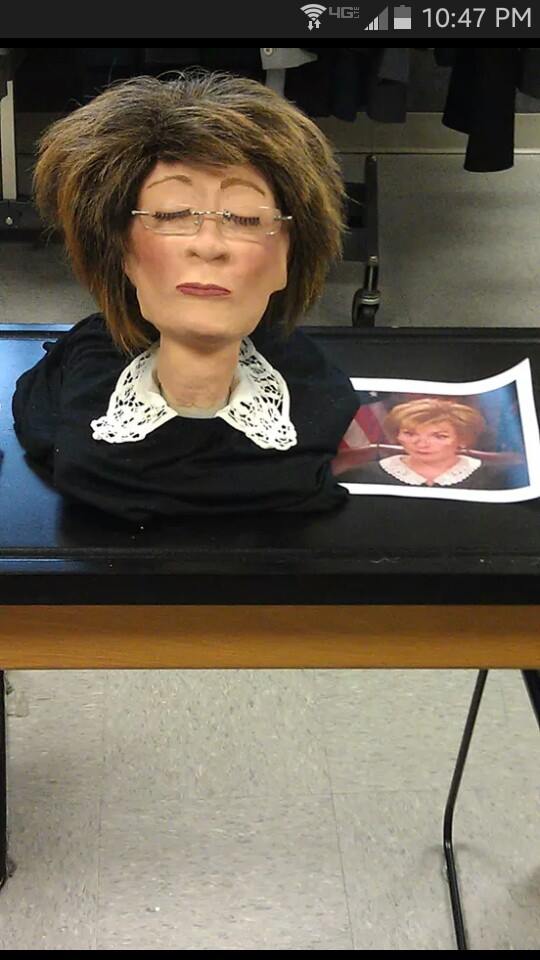

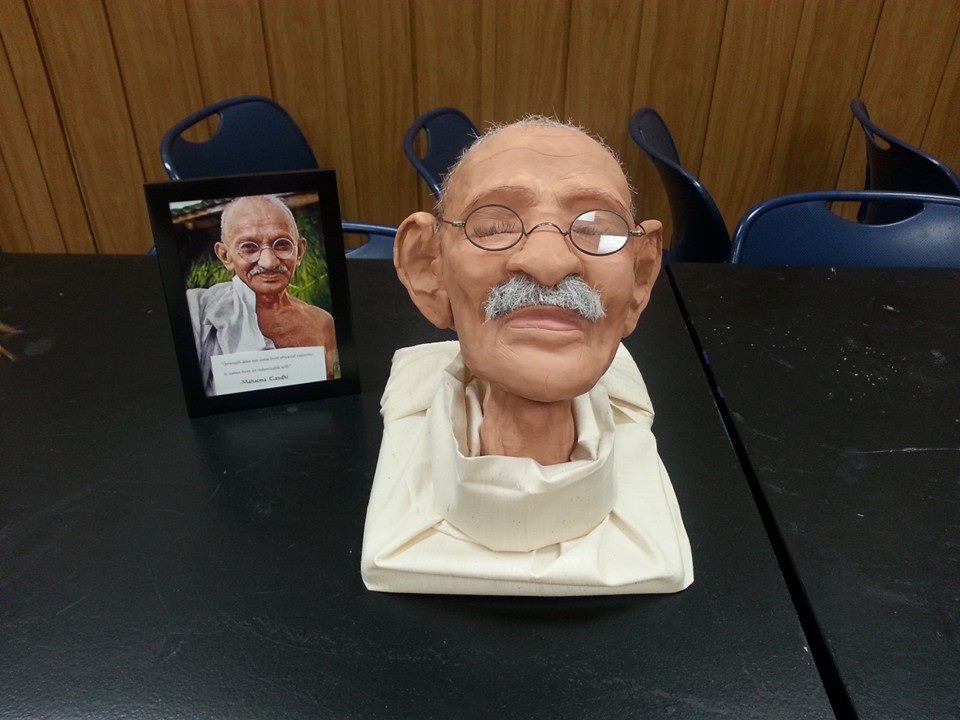

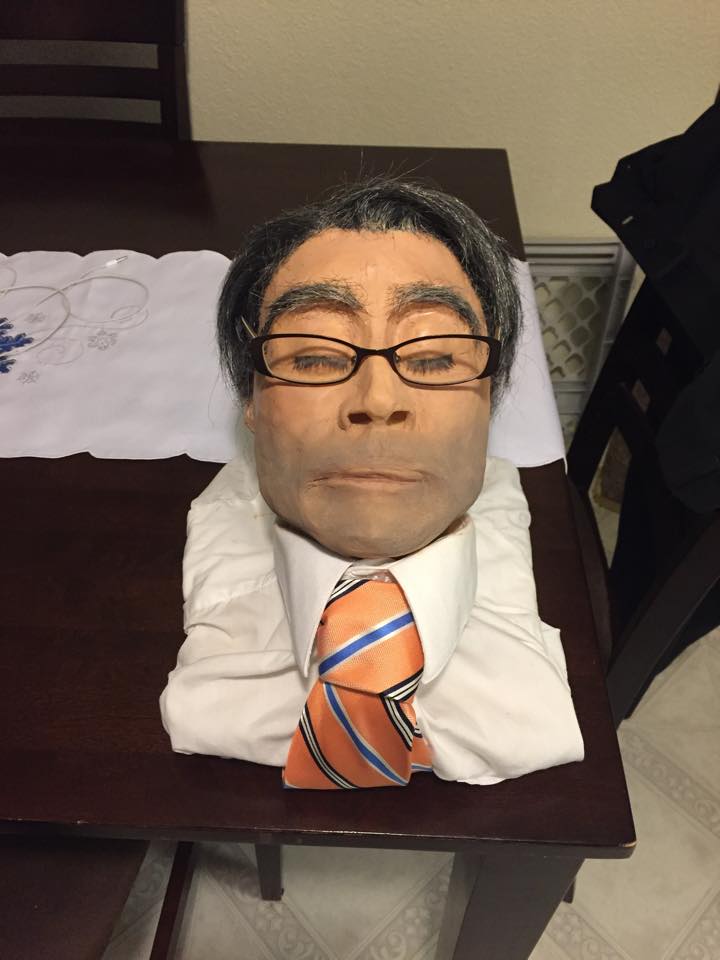

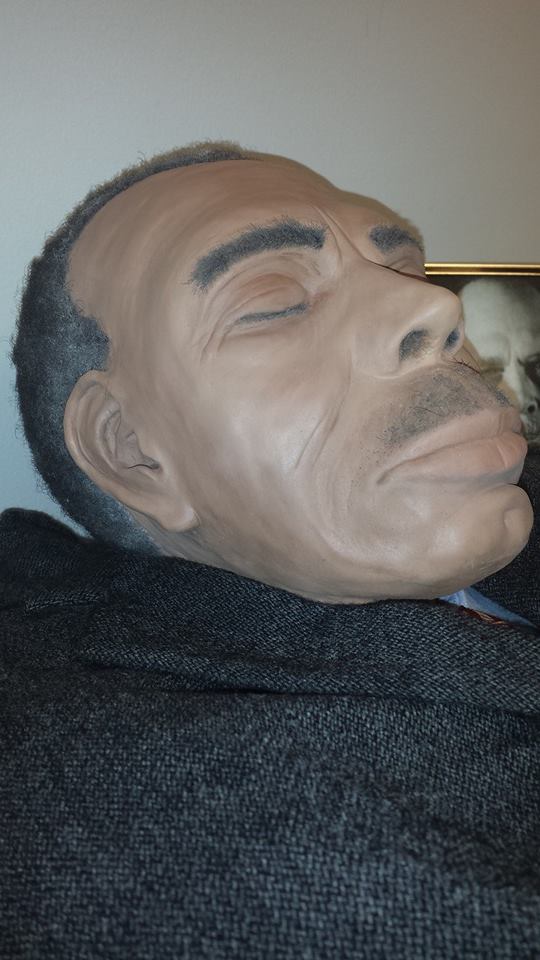

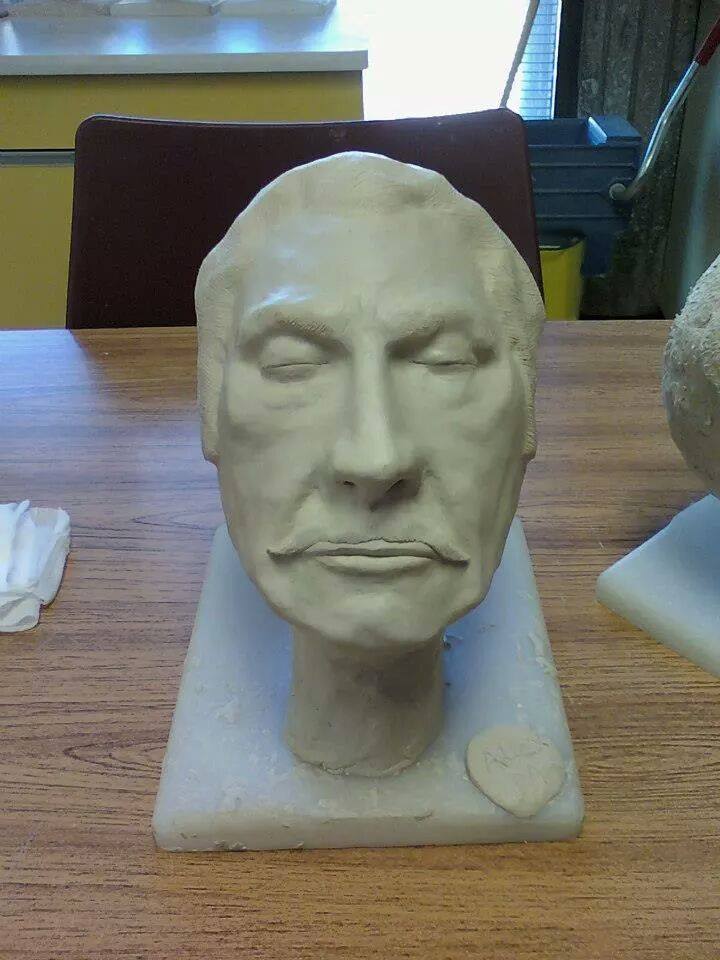

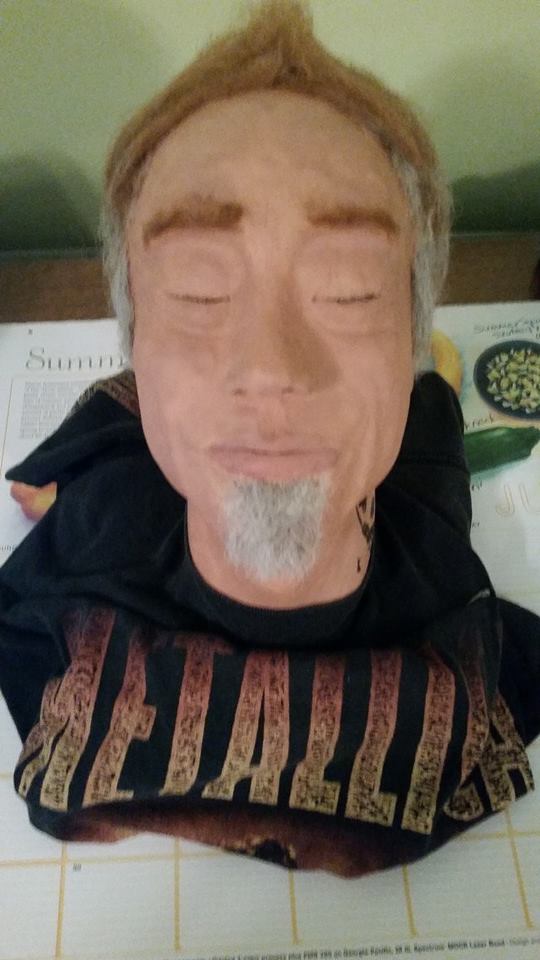

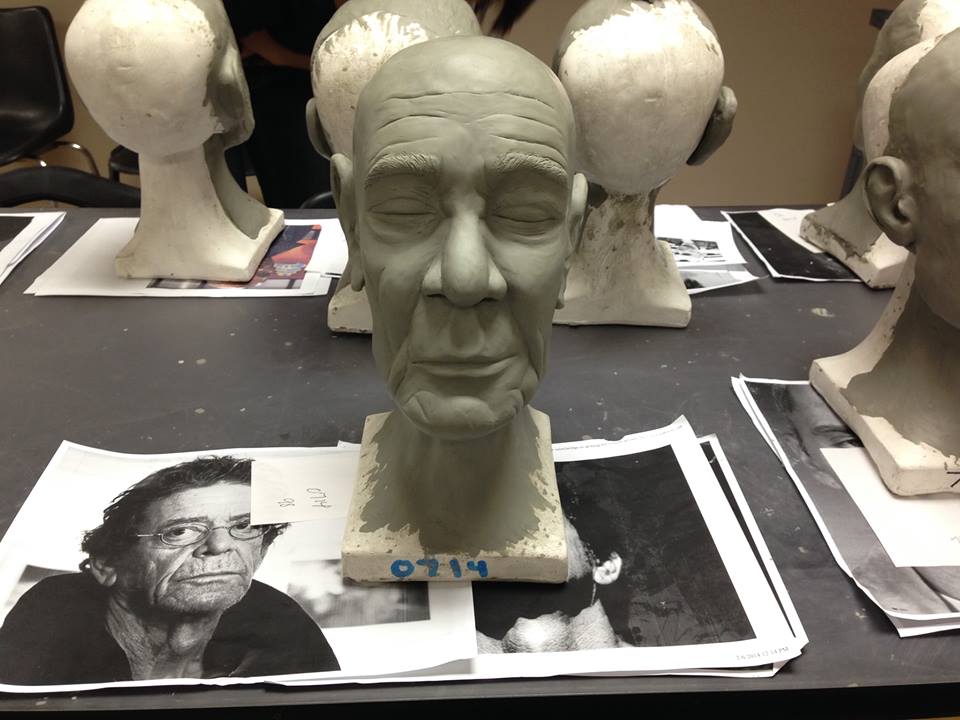

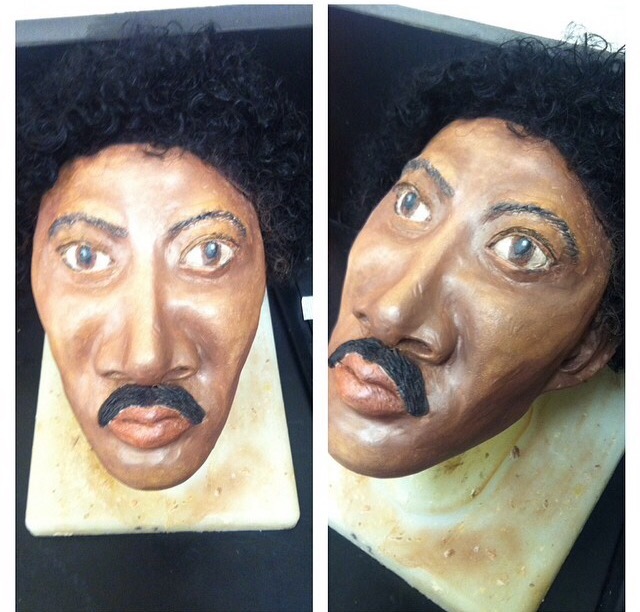

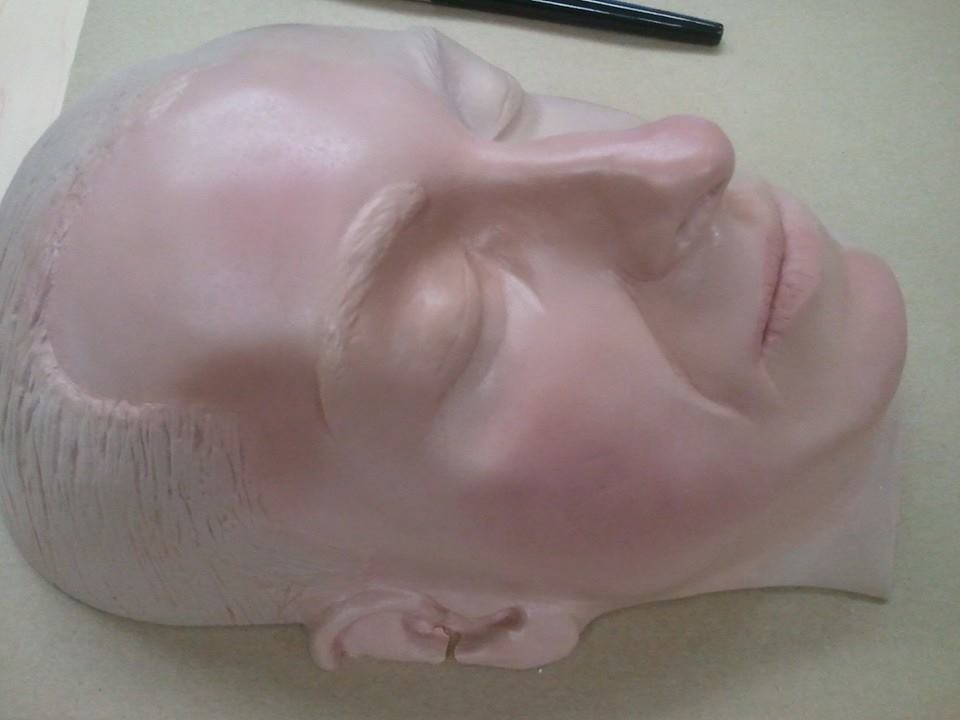

11 More “Wax Faces”

A couple days ago I posted “21 Spectacular Examples of what Mortuary Students do in Mortuary School”. There were a few honorably mentions that showed up late to the party. Here’s 11:

21 Spectacular Examples of What Mortuary Students Do in Mortuary School

Most of us who attend mortuary school were required to take a class called “Restorative Art”. The Restorative Art and Science textbook states, “Restorative art is defined as the care of the deceased to recreate natural form and color. In our attempt as funeral service practitioners to restore the deceased human remains to its most natural appearance, we predicate our efforts on the scientific understanding of the human facial and cranial form.”

The culmination of our “scientific understanding of the human facial and cranial form” is the “wax head.” We are given a plastic skull (see below) and a bunch of wax (or clay). Our job is to make the wax head look like an actual face. Some of us aren’t too good at it (mine was a poor resemblance of my wife), and others are spectacular.

On my Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook page, I asked those who have completed a “Wax Head” to show their work. Out of the nearly 100 who responded, I took the ones that garnered the most likes (although the Worf and Spock ones were my personal favorites, so I added them too).

One.

By Morticia Addams

Two.

Three.

Four.

Five.

Six.

Seven.

Eight.

Nine.

Ten.

Eleven.

Twelve.

Thirteen.

Fourteen.

Fifteen.

Sixteen.

Seventeen.

Eighteen.

Nineteen.

Twenty.

Twenty One.

If you’re interested in the life of a funeral director, you might be interested in my book!

The Break that Binds: The Central Paradox of Death Rituals

© 2006 David Goehring, Flickr | CC-BY | via Wylio

Today’s guest post is written by Isaac Pollak, head of a Jewish Chevrah Kadisha (Chevrah Kadisha is the “Holy Society” or organization of Jewish men and women who see to it that the bodies of Jews are prepared for burial according to Jewish tradition and are protected from desecration, willful or not, until burial)

Central to religious practice, rituals may often seem intentionally obtuse to the point of irrationality. This, in fact may be their very purpose. By devising rituals that at times seem to make little or no sense to the uninitiated, those who learn to perform the rituals, if not understand them, become part of a distinct community. The fact that rituals often don’t make practical or rational sense is exactly what makes them useful for social identification. The cognitive psychologist Christine LeGare has done a number of studies showing that rituals declare that you are a member of a particular social group. Lewis Mumford the social philosopher, historian and greatest urbanist of the 20th century, makes a clear case that what sets humans apart from other animals is not the use of tools but rather our use of language and rituals and that makes us “Community”. Sharing information and ideas among participants was the foundation of all societies and “community is the most precious collective invention”.

Although there are rituals designed for every aspect of the human life cycle, the rituals surrounding “DEATH” are often the least understood, yet the most often performed.. Even the irreligious may insist upon death rituals for themselves or their loved ones. Matthew Frank in his book Preparing the Ghost speaks about “our need to mythologize , ritualize and spin tails about that which we “fear.”

The greater the lack of comprehension the increased amount of the rituals with DEATH by far more ritualized than any other aspect of a society’s life cycle in every culture. The more the rituals the stronger the bonds of community and social identification. The life cycle events the least understood , emerge earlier and are more deeply rooted .

Witness the tragic murder of three young Israeli teenagers which bought every dimension of Judaism into a unified community-from Ultra Hassidic to Jews for Jesus. Everyone adopted and prayed for these young men ” kol Yisrael Arevim zeh l\L’zeh” all of us are responsible for one another. Death brought us community as nothing else ever could.

A life broken , an individual link lost, paradoxically strengthens the group unity and identity. Rituals give us a sense of control over an area where we have none. Mundane actions are suffused with arbitrary conventions and that makes it important to us and gives us a sense of “being in charge”. Rituals engage members of a community in the collective enterprise of building and sustaining a “PEOPLE.”

Jewish death rituals have a foundation that travels back in time 3000 years and has made us a community like none other. In fact, a new developing Jewish community, has an obligation to set aside ground for a cemetery before setting aside land for a synagogue. How wise were our Rabbis.

Let us preciously value these so vitally irrational traditions and hoary rituals that brings us together to pray, to improve ourselves and to elevate ourselves in response to mysteries we don’t comprehend.

Let me conclude by paraphrasing the German poet Rainer M. Rilke in his letters to a young Poet:

“I beg you to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign tongue. Don’t search for the answers , which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything . Live the questions now . Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”

*****

Isaac Pollak is President and CEO of an International Marketing Concern for the past 4 decades. He holds graduate degrees in Marketing, Industrial Psychology, Art History, and Jewish Material Culture from City College, LIU, JTS, and Columbia University. He has been the Rosh/head of a Chevrah Kadisha on the upper East Side of Manhattan, NYC, for over 35 decades, and is an avid collector of Chevrah Kadisha mortuary material cultural items, having several hundred in his own collection. He serves as chairperson of the Acquisition Committee for Traditional Material Culture at the Jewish Museum in NYC. Born and raised in NYC, married, with 3 children and 3 grandchildren.