Caleb Wilde

(218 comments, 980 posts)

Posts by Caleb Wilde

“The Day the Angels Fell”: A death positive novel for children (CHAPTER 1)

A couple days ago I shared a review and endorsement for Shawn Smucker’s children’s novel, “The Day the Angels Fell.” Here’s chapter 1:

I am old now. I still live on the same farm where I grew up, the same farm where my mother’s accident took place, the same farm that burned for days after the angels fell. My father rebuilt the farm after the fire, and it was foreign to me then, a new house trying to fill an old space. The trees he planted were all fragile and small, and the inside of the barns smelled like new wood and fresh paint. I think he was glad to start over, considering everything that summer had taken from us.

But that was many years ago, and now the farm feels old again. The floorboards creak when I walk to the kitchen in the middle of the night. The walls and the roof groan under the weight of summer storms. There is a large oak tree in the front yard again, and it reminds me of the lightning tree, the one that started it all. This house and I are two old friends sitting together in our latter days.

I untie my tangled necktie and try again. I’ve never been good at ties, probably because I never wear them. But my last friend’s funeral is this week and I thought I should wear a tie. It seemed the right thing to do, but now that I’m standing in front of a mirror I’m having second thoughts, not only about the necktie but even about going. She was my best friend, and although as children we would have done anything for each other, I’m not sure I have the strength for one last funeral.

Someone knocks on the front door, so I untangle myself from the tie and ease my way down the stairs, leaning heavily on the handrail. Another knock, and by now I’m crossing to the door.

“Coming, coming,” I say. People are in such a hurry these days. Everyone wants everything to happen now, or yesterday. But when you’re my age, you get used to waiting, mostly because you’re always waiting on yourself.

“Hi there, Jerry,” I say through the screen, not making any move to open it.

“I won’t come in, Samuel. Just wanted to apologize for my boy again.”

Jerry is a huge bear of a man with arms and hands and fingers so thick I sometimes wonder how he can use them for anything small like tying shoes or stirring his coffee. He’s always apologizing for his boy. I don’t know why—seems to me his boy simply acts like a boy. And because Jerry is always calling him “boy,” I can’t remember the child’s name. I’m not sure anyone ever told me what the kid’s name is.

“I heard he was throwing smoke bombs up on your porch this morning.”

“Oh, that. Well,” I begin, but Jerry interrupts me.

“I won’t hear of it,” Jerry says. “In fact, as soon as I find him he’ll be coming here in person to apologize.”

“That’s really not necessary,” I begin again.

“No. That boy will apologize.”

I sigh.

“Anything else, Jerry? How are the fields this summer?”

“Green, Samuel. It’s been a good summer so far.”

“Good, good,” I mumble, then turn and walk away because I’m too old to waste my time having conversations that don’t interest me.

“Oh, and I’m sorry about your friend,” Jerry calls to me as I begin the slow ascent up the stairs. His words hit me like a physical object, make me stop on the third step and lean against the wall. They bring a fresh wave of grief to the surface, and I’m glad he can’t see my face.

“Thank you,” I say, hoping he will leave now.

“The missus says she was a good, close friend of yours for many years. I’m very sorry.”

“Thank you,” I say again, then start climbing the stairs. One foot after the other, that’s the only way to do it. I wish people would mind their own business. I have no interest, at my age, in collecting the sympathy of strangers. Or near strangers. In fact, I can do without sympathy at all, no matter the source.

I still imagine myself to be self-sufficient, and in order to maintain that illusion I keep a small garden at the end of the lane. Sometimes, while I’m weeding, I’ll stop and look across the street at where the old church used to be. After the fire they left the lot vacant and rebuilt the small brick building on a lot in town, but the old foundation is still there somewhere, under the dirt and the plants and the trees that came up over the years. Time covers things, but that doesn’t mean they’re gone.

If I’m honest, though, I have to admit that during some gradual phase in my life I became too old to work the farm myself. There was a time, not long ago, when my farm fell into disrepair, and I thought it would be the end of me as well, because I couldn’t bear to watch so many memories collapse in on themselves. Then the family that moved into Abra’s old farm, Jerry and his missus and his “boy,” asked if they could rent my fields and barns. I said yes because I had no good reason to say no. Now they take care of everything and I live quietly in the old farmhouse, puttering in my garden or sitting on the large front porch, trying to remember all the things that happened the summer my mother died.

Jerry’s son looks to be about eleven or twelve, my age when it happened. I wonder what he would do if his mother died. I think he is scared of me, and I don’t blame him. I don’t shave very often and my hair is usually unruly. My clothes are old and worn. I know that I smell of old age—I remember that scent from when my father started walking with a cane.

Sometimes Jerry’s son will hide among the fruit trees that line the long lane and spy on me, but I don’t mind. I pretend not to see him, and he seems to have fun with it, climbing up to the highest branch and peering through an old tube, as if it is a telescope. Sometimes, though, when he gets to the top, I find myself holding my breath, waiting for him to fall. Everything falls in the end, you know. Everything that climbs high tumbles down to the ground.

I stare at the mirror again after climbing the steps and I wonder where all the time has gone. I pick up the necktie and try again, and my old fingers can’t quite get it right. I remember when I was a very young boy my mother would sometimes put a tie on me, her delicate hands weaving the smooth fabric in a magical way.

“There,” she would say, smiling, patting the knot of the tie, and looking rather pleased with herself. “Now you look like a young man.”

The boy reminds me of myself when I was his age. He runs around the farm with sticks and pretends they are swords and magic staffs. Those days seem so long ago. Now I move slowly, carrying only a cane that is nothing more than a cane. I don’t know if I have the power anymore to turn this cane into anything exciting, anything like a sword pulled from a stone or a gun that could kill an Amarok. Sometimes I feel like I have forgotten how to pretend.

I give up on the tie and sit with relief at the desk by the window that looks out over the front yard and the garden and the old oak tree. It’s rather eerie how the farm has returned to almost the same condition that it was in the summer my mother died, the summer of the fire. Sometimes when I look down the lane I expect to see her walking back up from the mailbox, or for my dad to wander in from the barns, dirty and ready for dinner.

After many years of wondering if I could get the story of that summer exactly right, I have decided to simply write it as I remember it. There’s no one else left who was there when it happened, no one to compare stories with, no one to agree or disagree with my own version. As I think through the story, I wonder if it’s even possible that everything happened as my memory tells me it did. It all seems rather incredible.

But one thing I’m sure of: After everything that happened that summer, life seemed fragile, like an egg rolling toward the edge of the table. It seemed like anyone I knew could die at any moment, and that feeling frightened me. But now that I’m old, and everyone I know has died, my own life feels almost unbreakable, like it will never give up.

Which reminds me of something that Mr. Tennin told me, in his thin, wispy voice, right at the end.

“Samuel,” he whispered. “Always remember this.”

I leaned in closer as the fire roared on the far side of the river.

“Death,” he said, pausing, “is a gift.”

I stare at the obituary sitting at the corner of my desk, the one that I cut out of the paper yesterday—such a small amount of writing meant to tell the story of someone’s entire life. I lift it up and it is light, almost see-through, and for a moment life seems fragile again, and temporary.

I know what Mr. Tennin said can be hard to believe, especially when staring death in the face. Death seems so horrible and huge, and when it comes for someone early, the last thing it feels like is a gift. Death, a gift? I would have shouted at someone had they said that to me at my mother’s funeral. But I’ve been on this earth for many years now, and I’ve seen many things, and I finally believe that Mr. Tennin might have been right.

Death, like life, is a gift.

This is how I remember that summer.

******

Right now Shawn dropped the Kindle edition price to $3.99 just for our Confessions of a Funeral Director community. It’s well worth the price of the purchase and the time to read it. You can find the paperback version HERE.

Obituary Prank from the Grave

Norma Brewer, 80, had been wheelchair bound for over a year, so you can imagine her family’s surprise when they read a prewritten obituary that she submitted to the funeral home before her death:

Norma Rae Flicker Brewer, a resident of Fairfield, passed away while climbing Mount Kilimanjaro. She never realized her life goal of reaching the summit, but made it to the base camp. Her daughter, Donna, her dog, Mia, and her cats, came along at the last minute. There is suspicion that Mrs. Brewer died from hypothermia, after Mia ate Mrs. Brewer’s warm winter boots and socks. Via Lesko and Polke Funeral Home

Damn dogs. Always eating socks and causing hypothermia.

Norma’s daughter said, in response to the surprise obituary prank, “It was just typical mom,” she said. “She always had stories, many of which were not true, but thought were funny.

All joking aside, this was a serious act of grace by Norma. To inspire laughter in your death, to lighten dark times and to give your loved ones something that is both a surprise and quintessentially you is really great way to go out.

Some people will have posthumous gifts delivered to their loved ones. Others have left posthumous letters and videos. All of these idea are magic … they leave a bit of yourself even after you’re gone.

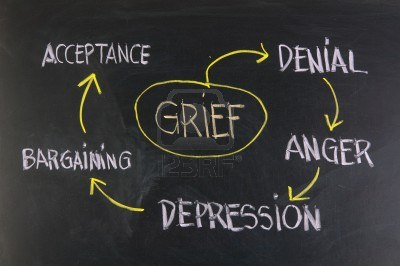

Pitfalls of Kubler-Ross

Today’s guest post is written by Chad Harris:

Ask most people what they know about grief, and they will likely mention that it’s made up of 5 stages:

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

Makes it all sound neat, tidy, and orderly, doesn’t it?

Problem is, grief is messy!

Kubler-Ross did not originally intend for her model to be widely accepted as a model of grief and loss – in fact, her stage theory came out of her work with those who were actively dying, not those who were grieving the death of a loved one. Yet, the medical establishment and the general public embraced this model, in no small part because it seemed intuitive and orderly. However, classifying them as stages diminishes the fact that people may not move through these thoughts, feelings, or actions in order. In fact, they may skip ahead, work through them out of order, go backwards between stages, or even repeat stages. Perhaps most troubling, such a model makes those around the griever more likely to think they know what the person is going through – and that they can helpfully tell the person what to expect next.

Did I mention that this is rarely the case since grief is messy?

In the years since Kubler-Ross’s work started gaining ground in the late 1960s, a number of alternate theories have been proposed, and while there is no one grand unified theory of grief – and no one theory can explain everyone’s grief (since it’s messy!), one that has gained much traction and that helps provide meaning to the rituals of mourning through which we express our grief is found in the work of psychologist Dr. J. William Worden.

In his 1982 book “Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy”, Worden proposed that when we are faced with grief, we make sense of that grief (as much as is possible) and find our way back to some semblance of daily functioning through the act of mourning – our public “face” of grieving a death.

Worden proposed that each grieving person undertakes four tasks in order to process the death of someone meaningful, and by doing so, a griever comes closer to finding their way to their new normal.

Worden’s Four Tasks of Mourning

- Accept the reality of the loss.

- Work through the pain of grief.

- Adjust to an environment in which the deceased is missing.

- Find a way to form an enduring connection with the deceased while embarking on a new life.

Accepting the reality of the loss is vital. In order to heal, we must first understand that we’re hurting and that something is not the same. Sadly, growth and change is often spurred by discomfort. While there are a number of ways to begin to either accept the reality ourselves or to help others, among the most effective are funerals/memorial services and using words that aren’t cloaked in platitudes or euphemisms. The loved one in question didn’t get lost, nor did he or she expire like a carton of milk. He or she died. People die. It’s part of the human life cycle, and it’s important to embrace this fact.

Working through the pain enables us to not feel stuck and to begin to find some level of healing. It keeps us active, engaged, and moving ahead, helping to keep us from feeling stuck. Will we feel stuck sometimes? Of course! As long as we remain open and honest, though, we will make our way forward in our own time and in a way that makes sense to us.

Adjusting to an environment in which the deceased is missing does not mean forgetting the person existed. It merely means understanding that our worldview has been irrevocably changed, and though the person is no longer physically present, our memories will keep them with us.

Finding a way to create an enduring connection means honoring the person through our actions and carrying them with us in our hearts. Pictures, favorite books, or even volunteer activities that you do in their memory can help create this lasting, meaningful connection. As long as we hold the person close to us and honor that connection, they are not lost to us, even if they may not be physically present.

Worden’s tasks allow grievers to move ahead at their own pace. Yes, they are placed in some semblance of order, but they are tasks, and not merely things that happen to us or thoughts, feelings, or emotions we are carried through in a passive manner – which is how a reliance on the Kubler-Ross model can often make people feel. Worden’s tasks are active. Worden’s tasks empower grievers, giving a greater sense of control than models like Kubler-Ross’s.

Worden’s model isn’t perfect, of course. It appears quite linear and it may also seem as though there is no room for sliding backwards amid the tasks. After all, grief is messy, and a griever may often feel waylaid by what Dr. Therese Rando calls “sudden, temporary upsurges of grief”, or STUGs. No matter how long it has been since our loved one has died, we are going to have moments when we are a complete mess and miss the person even more than we thought we could – and we may feel like all of our progress to this point has been for naught.

It’s important to remember, though, that on any journey, no matter the model we subscribe to, we stumble – and that’s especially likely on a journey like the one through grief that is never-ending. Whether we’re grieving or supporting someone who is, it is important to remember that we will stumble and struggle. These are not failures…they’re simply realities that happen. We may have moments of sadness, even though we feel as though we’ve moved far beyond that point – or we may have moments of joy when we feel as though it’s not appropriate. Never judge nor apologize for what you or someone else is feeling. That’s our subjective reality in the moment, and everyone is entitled to those feelings.

*****

About the author: Chad Harris is a graduate student at Hood College in Maryland, where he is pursuing a master’s degree in thanatology, as well as coursework in gerontology. He also holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Central Arkansas, as well as a master’s degree in social work from Case Western Reserve University. He is currently researching the role of mass media in shaping people’s perceptions of death and the impact of media coverage on grief and mourning, with the hopes of helping promote more responsible coverage of tragic events.

The Strange Premature Burial of Angelo Hays

© 2013 greg westfall, Flickr | CC-BY | via Wylio

Mental_floss wrote an article documenting the premature burial of four individuals. This one is especially interesting:

… 19-year-old Frenchman Angelo Hays “probably the most remarkable twentieth-century instance of alleged premature burial.” In 1937, Hays wrecked his motorcycle, with the impact throwing the young man from his machine headfirst into a brick wall. Hays’ face was so disfigured that his parents weren’t allowed to view the body. After locating no pulse, the doctors declared Hays dead, and three days later, he was buried. But because of an investigation helmed by a local insurance company, his body was exhumed two days after the funeral.

Much to those at the forensic institute’s surprise, Hays was still warm. He had been in a deep coma and his body’s diminished need for oxygen had kept him alive. After numerous surgeries and some rehabilitation, Hays recovered completely. In fact, he became a French celebrity: People traveled from afar to speak with him, and in the 1970s he went on tour with a (very souped-up) security coffin he invented featuring thick upholstery, a food locker, toilet, and even a library.

To read the remainder of the article, click HERE.

Morgue worker claims, “I have sex with corpses.”

There’s been three necrophilia cases that have made the national news in the past month. The following story is perhaps the most disturbing because — unlike the other two — it involves a “mortuary employee.”

First the story, and then I’ll provide some rather strong commentary:

An employee at a mortuary in Ghana has told how he had sex with dead women “many, many times” – claiming necrophilia is part of the job training.

The man claimed he worked in a morgue at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, where he says he had sex with the corpses, reported VibeGhana.com.

Sharkur Lucas revealed that he was unable to get women to go out with him because of his ‘morbid’ job – so he had sex with the dead instead.

“I wanted to marry but the girl says I am a mortuary man,” he told Ghana television station Adom TV.

….

Since his interview, Lucas has been sacked by his employers and admits he is now being hunted by police – although he fails to see what he has done wrong.

But when the interviewer raised the question of mental health problems, Lucas dismissed the claims.

“I am OK, I am OK sir,” he insisted. via Mirror

I’m not a psychologist nor a psychiatrist and have a very superficial understanding of mental health. I also have little background in the academic spheres of human behavior. With that said, I think we can all agree that such acts are both incredibly sick and unspeakably wrong and undeniably illegal.

Before the thought enters your mind, this is NOT something even remotely normal among “death workers.” Most everyone (you and me) have encountered dead bodies at funerals, or perhaps hospitals, and I think we can all agree that our reactions to the deceased is always some mixture of fear, bordering awe, bordering honor. Honor is how I always view a dead body, and I think funeral directors, mortuary works and the like agree.

Mr. Sharkur Lucas is the extreme outlier and I expect he’s not fit to work with either the dead or the living.