Caleb Wilde

(218 comments, 980 posts)

Posts by Caleb Wilde

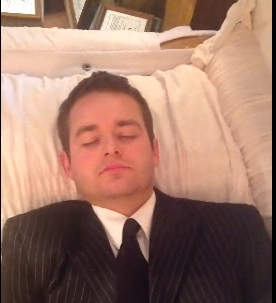

Book Promo Trailer

No worries, friends, I didn’t solicit a random corpse to *play* the dead person in this video. The esteemed actress was none other than my wife, who willingly agreed to play the part because she really, really, really loves me (and I promised her infinite back rubs for the next calendar year).

With that aside, here’s the promo video for my book. It captures the heart of my words.

Love you all and thanks helping me launch this book and its message into the world.

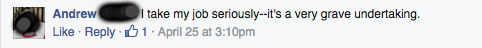

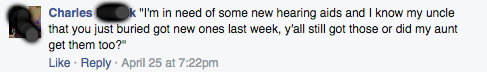

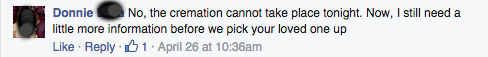

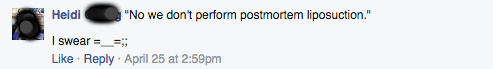

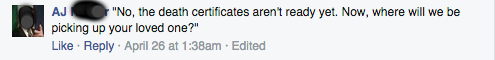

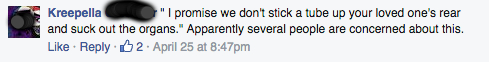

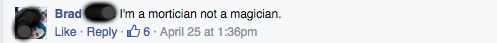

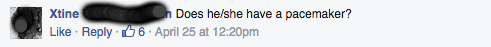

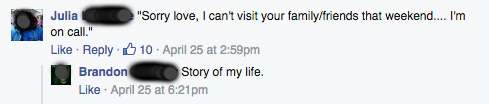

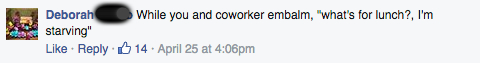

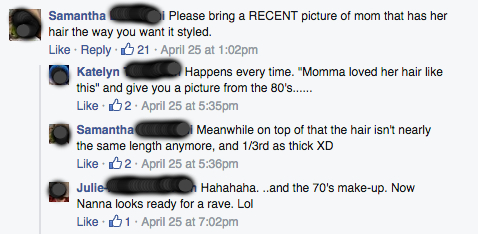

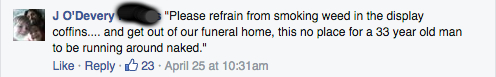

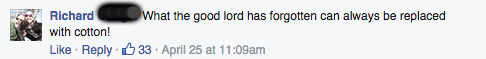

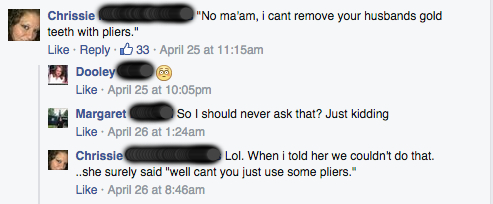

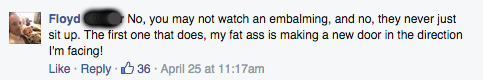

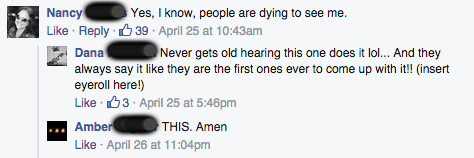

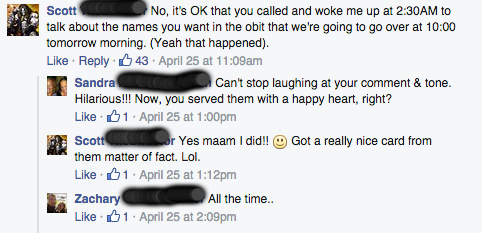

20 Things Funeral Directors Say

This post is collected from the Confessions of a Funeral Director Facebook community:

One. Two.

Two. Three.

Three. Four.

Four. Five.

Five. Six.

Six. Seven.

Seven. Eight.

Eight. Nine.

Nine. Ten

Ten

Eleven.

Eleven. Twelve.

Twelve. Thirteen.

Thirteen. Fourteen

Fourteen Fifteen.

Fifteen. Sixteen.

Sixteen. Seventeen.

Seventeen. Eighteen.

Eighteen. Nineteen.

Nineteen. Twenty.

Twenty.

If you’re interested in the life of a funeral director, here’s my story, told with humor, spirituality, and transparency.

10 Ways You Can Be Death Positive

Death positivity is simply embracing that part of ourselves that we so often deny: our mortality. As an extension of embracing mortality, it’s also being willing to move towards dying, death and the dead. By that definition, being death positive doesn’t mean that you wear black all the time and avoid the sunlight at all costs. It doesn’t mean that suicide ideation is your go-to for a good time; nor does it mean that you rejoice anytime and everytime someone dies.

Here are 10 things it can mean:

One. Talk about your dead

I just had a gentleman come into the funeral home to make a payment on his brother’s funeral bill. We were talking about funerals and death, and out of the blue he said, “My biggest fear is that 10 years after I’m gone no one will remember me.” We talked some more and we arrived at the conclusion that the reason we don’t talk about our dead isn’t because we don’t love them, but because we’re afraid it’s taboo to talk about them. But, it isn’t taboo. It isn’t morbid. It’s honest, loving and human. Keep your dead alive by actively remembering them.

Two. Hang out with Older People

The most death positive people in the world are usually those that are closest to death. I’m not against nursing homes or rehab centers. We certainly need them, but the fact that they house the most death positive people in society, thereby cutting them off FROM society, makes it really hard for those of us who are younger to learn from their wisdom and mortality acceptance. Nursing homes are essentially taking much of our financial inheritance, but more problematic is they take our death positive inheritance that should be passed down from one generation to the next, from the older generation to the younger generation.

Three. Go to that funeral

Death creates a hole in our lives and our world. It’s like an earthquake that shakes the world we once knew. Funerals are a time when we can reaffirm meaning, love, community, goodness and even humor. They allow us a space to come together and affirm that life is changed, but it still continues on. Funerals are a storytelling practice that keeps the identity of our family alive even when one of our members has died.

I know. They’re awkward. I’ve been to thousands of them. And it’s easy to find excuses to NOT go. But funerals are one way WE cope and acknowledge death. They are, in their most basic form, a communal embracing of death.

Four. Meditate on Mortality

Buddhism’s contemplation of death is called “maraṇānussati bhāvanā”, or simply “Maranasati” (death awareness). Here’s a little tidbit on a guided mortality meditation from the Kadampa Center:

To generate an experience of death’s inevitability, bring to mind people from

the past: famous rulers and writers, musicians, philosophers, saints,

scientists, criminals, and ordinary people. These people were once alive—they

worked, thought and wrote; they loved and fought, enjoyed life and suffered.

And finally they died.

You can also bring to mind your inheritance, and how you should will “Caleb Wilde” as sole heir of all your cash. Not cats. Cash.

Five. Acknowledge Other People’s Dead

Those older ladies who send out condolence cards on the daily? They’re the OGs of the Death Postive Movement.

A card. A kind Facebook message. A plate of bacon given to your bereaved (non-vegan, non-Jewish and non-Muslim) friends. Saying the name of your friend’s deceased loved one. These small acts go a long way.

Six. You Could Try “Coffin Therapy”

This is an actual thing that is taking off in parts of Asia. You lay inside a coffin (or casket), contemplate your death and let death wash its life over you. From my readings, most participants find it very enlivening. Although, from personal experience, make sure you choose the deluxe Tempur-Pedic casket if your “coffin therapy” lasts for more than two hours.

Seven. Embrace Your Own Mortality

Mortality isn’t just about death, it’s also about all the things that make us limited, needy, vulnerable, hungry, sexual and human. We have been conditioned by our religious heritage and by societal mores to shame many of the things that come with our mortality. Instead of shaming, embrace.

Eight. Have “The Talk”

It’s not morbid to talk about your death, or ask — say your parents — about their death. This is healthy. It’s healthy to recognize the inevitability that you, and I, will die. And it’s important to express your dying desires through a living will, and how you want your death arrangements to look when it happens.

Nine. DEAD BODIES AREN’T DANGEROUS

If you cared for them in life, care for them in death. Death care isn’t rocket science. Nor do death bodies harbor the plague. If love tells you to care for your dead, do it. Find ways to work with the funeral home, or have a home funeral. The more active you can be in caring for your loved one, I believe the healthier your grief.

Ten. Read books about death positivity.

If you liked the content of this article, (in Billy Mays voice), BUT WAIT. THERE’S MORE. The ideas that you just read are the essential elements that I write about in my new book. If you don’t like the book, I’ll give you a “Two for the Price of One” coupon to our funeral home.

10 Ways the Funeral Industry Has Failed

Don’t worry, I’m going to write a post about the ways the funeral industry has succeeded. But for now, here are ten ways we’ve failed.

One. Disconnected from Community

This is where things start to go horribly wrong. If you don’t have a personal investment in the community, if you don’t love the customers you work for, if you don’t live around them, send your kids to the same schools, shop at the same places, you lose the accountability of love and connection. Once that accountability is lost, death care ethics are on a much more slippery slope. This is why — for the most part — local, privately owned funeral homes are more likely to retain their good name, while large, corporate funeral homes tend to be slightly disconnected and slightly more likely to see this as primarily a business.

Two. Bad at receiving criticism

We’re notoriously bad at receiving criticism. To be fair, nobody is good at it. I mean, who likes to be told that we’re a bunch of racketeers over and over and over again? I know I don’t. Unfortunately, some of that criticism is true! We’re good at listening to market changes, in fact, our funeral director magazines are packed with advice on how we can respond to our customer’s wishes, but when constructive criticism comes from a customer, most of us are too biggety to listen.

Three. Intentionally Kept our Practices Hidden

God forbid we tell you what we do with your loved one. God forbid we publically write about what we do with your loved one. God forbid we blog about it (GASP!!!).

Four. Pushed Embalming Too Hard

Embalming is THE American Way of Death, or at least it was The American Way of Death. Yes, Jessica Mitford popularized that term with her book that holds the same title, but it was funeral directors who coined the term. The term was coined in a response to criticism from religious circles that claimed embalming was a pagan practice (the Egyptians did it for religious, but not Christian reasons). In response, funeral directors said, “No, embalming isn’t pagan, IT’S AMERICAN!” But that America was the America of nearly 80 years ago. America isn’t the same, but funeral directors still want it to be. MAEA! Make America Embalmed Again!

Five. No Support System for Funeral Directors

This is on two levels: funeral directing — like many professions — started as a trade, where the apprentices were trained by masters. Most states (all states?) still require a year of apprenticeship in order to gain licensure, but that apprenticeship needs to continue long after we become licensed. We need mentors to walk us through this trade. Two: we need support groups of some kind that can catch us when we’re falling from the burnout and compassion fatigue that too often comes with this line of work. Currently, most of us have neither.

Six. Too Often Erred on the Side of Business

We should be erring on the side of service. This perspective changes the way we approach money, and it changes the way we approach people.

Seven. Narcissism Checks

We’re called to be directors, to display confidence, knowledge, authority, and strength during people’s weakest moments. But this environment that asks us to lead can too often enable us to self-enhance. We talk over our heads, project authority in situations that are best left to the family and tense up in disdain whenever we’re questioned. There needs to be better checks and balances in place to keep us from sliding towards narcissism.

Eight. Too Much Professionalism

There’s not wrong with being professional. In fact, funeral directors should embody respect, courtesy, and kindness. But, professionalism says something more. It makes a distinction between those who are the professionals and those who are amateurs. Let’s be very clear about one thing: a funeral director’s education, a funeral director’s experience makes them good at helping families with their funerals, but LOVE, and only love, makes someone the best of professionals when dealing with their own deceased. That is, it’s love, and not foremost education and experience, that gives you authority with a dead loved one. In an attempt to embody professionalism, we funeral directors have stolen death care from the true professionals.

Nine. Like Most Industries, WE NEED MORE WOMEN

Amen and amen.

Ten. At times, we’ve failed you

Most of the women and men in the funeral profession are good, smart and service-oriented. But some of us aren’t. And even the good ones can fall into the traps of this business. For that, we’re sorry. We’re sorry if we’ve failed you. We can do better. We will do better.

If you’d like a personal, transparent view of what it’s like to be in the funeral profession, please consider supporting my writing by pre-ordering my book:

On that Decaying Foot that Popped out of the Ground in a New Jersey Cemetery

“I’m so overwhelmed. I’m very stressed, depressed because I’ve never, ever been to a funeral before and seen anything like this.”

The family is considering a lawsuit, and I’m not diminishing the family’s feelings or experience. After reading the article, it does seem like the cemetery could have handled things a little bit better. Although they may not have been able to stop the foot from popping out on Mr. Butler’s casket, they could have been more sensitive in explaining to the family how it happened.

If you’re interested in seeing the dirty of death, and yet the beauty of it, I wrote a book about it: