Caleb Wilde

(218 comments, 980 posts)

Posts by Caleb Wilde

About that really mean (and viral) obituary …

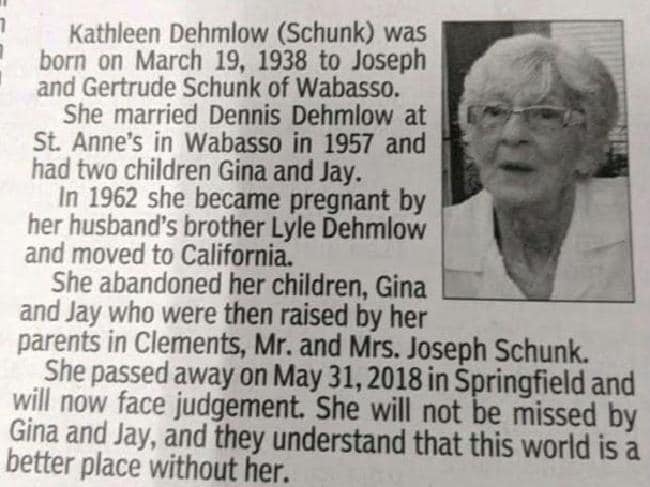

Obituaries rarely go viral, but when they do it’s usually for their creativity, originality, or inspirational message. Sometimes, though, they go viral for their vitriol. Below is the latest viral vitriol obituary that’s making it’s rounds all over the internet:

Picture: Rewood Falls Gazette

As horrible as this obituary is, it pales in comparison to some others I’ve read. For example:

Marianne Theresa Johnson-Reddick born Jan 4, 1935 and died alone on Aug. 30, 2013. She is survived by her 6 of 8 children whom she spent her lifetime torturing in every way possible. While she neglected and abused her small children, she refused to allow anyone else to care or show compassion towards them. When they became adults she stalked and tortured anyone they dared to love. Everyone she met, adult or child was tortured by her cruelty and exposure to violence, criminal activity, vulgarity, and hatred of the gentle or kind human spirit.

On behalf of her children whom she so abrasively exposed to her evil and violent life, we celebrate her passing from this earth and hope she lives in the after-life reliving each gesture of violence, cruelty, and shame that she delivered on her children. Her surviving children will now live the rest of their lives with the peace of knowing their nightmare finally has some form of closure.

Such obituaries garner a number of reactions. Some people find some vicarious satisfaction when seeing bad people publically shamed. Some are simply saddened that one life could cause so much pain and hurt that it’d prompt such an obituary. Others are angered that the family would publically shame the dead … who have no ability to defend themselves Still, others think it’s cathartic, a healthy way for victims to cope with the pain and violence

Shaming of the dead is nothing new. Historically, using an obituary to shame the deceased is charitable, at least compared to some of the other ways we’ve done it.

We only have to go back to Muammar Gaddafi’s death. Remember him? The Libyan despot? Remember how photos of his bloated and mutilated corpse flashed across TV screens, news websites, and newspapers? THAT is death shaming.

In many cultures, if you want to show contempt to the deceased, you bury them facedown.

Criminal’s bodies have often been put on display like pieces of meat in a butcher shop.

And the dead bodies of the defeated during war times are often disrespected in unmarked graves, or hung on buildings, bridges, and stakes.

In my book, I talk about something I call “active remembering”. I talk about how we usually remember the dead passively, but active remembering is doing it intentionally. It’s intentionally bringing the dead into the spaces of the living.

There’s a whole chapter dedicated to active remembering in my book, and the assumption is that we actively remember those that we love. But, there’s also an active remembering that’s based on hate. The family of Kathleen Dehmlow is practicing active remembering. And they’re doing it very well because it seems MANY people know about Kathleen and her less than virtuous life.

I guess this is how I feel about obituary shaming: I wish we could practice active remembering that’s based on love as well as the family of Kathleen did in hate.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

Why I’ve Stopped Being Nice (And Why You Should Stop Being Nice too)

Somewhere along the way, “being nice” became a supreme virtue in the United States. In fact, I think it may have taken the place of it’s predecessor … “being tolerant.” I never liked the word “tolerant”, and I’ve come to dislike the word “nice” for the same reasons I cringed at “tolerant”

“Tolerant” is an easy virtue to dislike, not because I think we should insulate ourselves from those who aren’t like us. Not because I’m racist, homophobic, or a religious bigot. I don’t like that word because all it does is ask us to “put up” with differences. I’m a white, heterosexual male. I don’t tolerate African Americans. I don’t tolerate homosexuals. I don’t tolerate women. Tolerate is something you do with an annoying younger sibling. Tolerate is what you do when you’re stuck in traffic and can’t do anything about it.

I open my heart to understanding a person and perspective that I can only see if I’m willing to put myself in someone else’s shoes. I don’t expect them to teach me (that’s not their job). But I do ask them questions and I listen to their responses because I’m interested in loving, understanding and celebrating differences, not just tolerate the differences. I celebrate my LGBTQ friends, POC, and religious diversity because I’m doing more than tolerate, I’m learning.

“Nice” is equally as empty a term.

As a funeral director, I’m expected to be supremely nice. Like, the nicest person ever. Like, picture the nicest person you know and then double their niceness is the kind of nice funeral directors are supposed to have. And there was a point in my career that I thought “being nice” was one of the main parts of my job. But, no longer.

I stopped being a nice funeral director when I saw how nice people tend to be enablers.

I stopped being a nice funeral director when I saw how nice people can’t communicate personal boundaries.

I stopped being a nice funeral director because I learned how to say “no.”

I stopped being a nice funeral director when I saw nice people getting burned out in this industry.

I stopped being a nice funeral director when I saw that grieving people don’t actually want a nice funeral director.

I stopped being nice when I saw how it’s as fake as the “how are you doing?” greeting.

Nice is what rich people are when they’re dealing with poor people. It’s the next step after tolerance. It’s tolerance, but with a smile on top. It’s what a CEO is when he does some PR with his minimum wage workers. It’s what white people are when they go to third-world countries. It’s how you act when a salesman calls your phone.

“Nice” is an okay virtue, but it’s so far down my list of important virtues, I don’t even try anymore.

I do, however, try to be empathetic, recognizing and embracing the humanity in those around me.

I do try to be vulnerable by making myself open to different perspectives, and honest about my own.

I try to be intelligent and educated, so that I know what I know and — more importantly — know what I don’t know.

I try to be present, fully engaged with the person(s) I’m talking to (And I’ll admit, this one is the one I fail at the most).

I try to be welcoming and hospitable by enabling people to be themselves around me and not what they think they should be around me.

I also to be true to myself and set healthy boundaries for my personal life and family.

But nice? Nah. I’m not trying to give off the impression that I’m nice. In fact, when people describe me, I hope “nice” is one of the last words they use, because I’m no longer trying to be a nice person or a nice funeral director. I’m pretty sure it’s one of the least important virtues if it’s a virtue at all.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

Kindle Version of my Book Lowered to $1.99

$1.99. For a limited time, HarperOne lowered the cost of the Kindle edition of my book to $1.99. So, for the next couple days, instead of a Big Mac, you can buy my book. You can skip that Dairy Queen ice cream cone, or eat the Chilis chips without the guacamole, instead of your regular Venti Quad, Nonfat, One-Pump, No-Whip, Mocha, you can downgrade to a tall for a day. But, don’t skip the Waffle Fries from Chick-fil-A. Buy the Waffle Fries. Always buy the Waffle Fries.

Anyways, $1.99 for the next couple days. It’s a deal. Just click the picture to speed over to Amazon: link below.

link below.

A Letter to the Good Funeral Director Working at a Bad Funeral Home

Author: Stephan Ridgway Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/stephanridgway/ Title: Raj’s funeral Year: 2011 Source: Flickr Source URL: https://www.flickr.com License: Creative Commons Attribution License License Url: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ License Shorthand: CC-BY

You joined this business because at some point in your life you realized that you could do something good in death care.

Maybe you lost a loved one, and you wanted to use your pain and experience to help others walk through the difficulty.

Maybe a funeral director’s love and helpfulness inspired you to want to be the same.

Maybe you felt called to the dismal trade, knowing that deep inside you resides a resilience that few other people possess.

Whatever your reason for working in death care, the end was clear: you pursued this profession because you knew something good could come of it.

Then you started to look for a job. And the market was much tougher than you realized. The business was harder to crack than you could have imagined. The family-run funeral homes that you wanted to work for didn’t have any open positions. And the large, machine-like homes only offered positions with tough hours and cheap pay.

Whatever your story, you either ended up at a funeral home that you thought was great, or you ended up at a funeral home that was less than ideal.

*****

For some of you, you worked your way up from the bottom. You put in your due. The night shifts. You worked on holidays. You cleaned the prep room. You parked the cars. You mowed the lawn. You worked with Larry, the son-in-law of the owner who constantly makes off-color and sometimes sexist jokes.

Or maybe you got stuck with Robert, the owner’s nephew who slacks off, rarely pulls his weight, and constantly complains.

Then there’s John/Johanna, the supervisor. When he/she’s in front of the public, he/she’s the consummate professional: caring, compassionate and consistent. But when he/she’s out of the spotlight, his/her ability to supervise is nowhere near his/her ability to be a funeral director. His/her temper is short, he/she blames failures on everyone else except himself/herself and the only time you’ve ever seen him/her smile is when he/she’s bragging about himself/herself or leaving for vacation.

You’ve finally worked your way up the ladder and now you’re making arrangements … doing the thing you’ve always wanted to do.

Except, you’re not just expected to care for people, you’re expected to care primarily for the bottom-line of the business. The tag-line of the funeral home would imply that families come first, but the truth you’re realizing more and more is that it’s really the dollar.

Upsell the caskets.

Upsell the packages.

Push embalming.

Obfuscate, obfuscate, obfuscate so that families don’t know the money saving options.

Use lines like, “This is the casket your loved one deserves.”

And, “This casket honors your dad’s life like no other.”

Or whatever line the kids are using these days.

*****

First off, if this is you, I’m sorry.

Unmet expectations are difficult to digest. Lousy supervisors make a difficult job even more demanding. And finding out that — for some funeral homes — it really ISN’T all about service … finding out that many of these dudes are in it for the money … that discovery is enough to deflate the reason you pursued this career in the first place.

There’s a couple options for you at this point: Sometimes, the good funeral director in a bad funeral home holds onto his/her job. They kowtow to the system because — let’s face it — it might not be the best income, but it’s a job.

Some quit. Let me correct myself … many quit. They’ll go looking for a better funeral home with better people. And those funeral homes are out there. They really are.

Others will try to start their own funeral home, or buy out an old one so that they can implement their original vision of what death care should look like.

But for many, they wash their hands of this industry and make the healthy choice to find another profession.

To the good funeral director currently working at a bad funeral home, I’m not going to promise you that it get’s better. Some things don’t get better. Some things need to be burnt down (I’m talking figuratively of course). Some things can be changed, through hard work and a labor of love, to be something better. Some things need to be abandoned.

Whoever you are. Wherever you’re at. Let me say this: death care needs you, but you don’t need it.

If you entered this business with a heart to serve, YOU are what families need when they encounter a sudden death and have minimal funds. YOU are what families need when they just want someone to honestly tell them their options. YOUR ability to bring some sense of order to chaos is exactly what we need.

But, let me be clear: YOUR DESIRE TO SERVE DOESN’T NEED THIS INDUSTRY. That heart to serve can play out in so many different professions. EMT. Nursing. Coroner. Medical Doctor. Anywhere, really. Because the world always has a shortage of people who genuinely want to help others, and if you genuinely want to help others, you’ll never have a shortage of opportunities.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

The Story of My Death Podcast is Back

Hey, guys. A couple years ago Shawn Smucker, Bryan Allain and I started a podcast called, “The Story of My Death”. We ran it for two seasons and then life took over and season three never materialized.

Shawn and Bryan were kind enough to let me run Season 3 on my own.

In this episode, guest KJ and I talk about her experience living with terminal cancer.

You can listen to the episode by clicking below. Or, you can subscribe on iTunes (or whatever feed you use) by searching “The Story of My Death.”