Pitfalls of Kubler-Ross

Today’s guest post is written by Chad Harris:

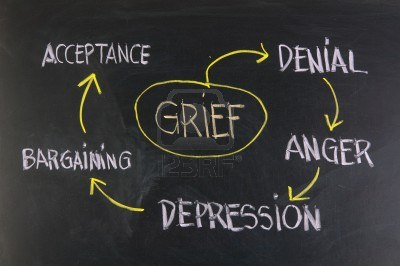

Ask most people what they know about grief, and they will likely mention that it’s made up of 5 stages:

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

Makes it all sound neat, tidy, and orderly, doesn’t it?

Problem is, grief is messy!

Kubler-Ross did not originally intend for her model to be widely accepted as a model of grief and loss – in fact, her stage theory came out of her work with those who were actively dying, not those who were grieving the death of a loved one. Yet, the medical establishment and the general public embraced this model, in no small part because it seemed intuitive and orderly. However, classifying them as stages diminishes the fact that people may not move through these thoughts, feelings, or actions in order. In fact, they may skip ahead, work through them out of order, go backwards between stages, or even repeat stages. Perhaps most troubling, such a model makes those around the griever more likely to think they know what the person is going through – and that they can helpfully tell the person what to expect next.

Did I mention that this is rarely the case since grief is messy?

In the years since Kubler-Ross’s work started gaining ground in the late 1960s, a number of alternate theories have been proposed, and while there is no one grand unified theory of grief – and no one theory can explain everyone’s grief (since it’s messy!), one that has gained much traction and that helps provide meaning to the rituals of mourning through which we express our grief is found in the work of psychologist Dr. J. William Worden.

In his 1982 book “Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy”, Worden proposed that when we are faced with grief, we make sense of that grief (as much as is possible) and find our way back to some semblance of daily functioning through the act of mourning – our public “face” of grieving a death.

Worden proposed that each grieving person undertakes four tasks in order to process the death of someone meaningful, and by doing so, a griever comes closer to finding their way to their new normal.

Worden’s Four Tasks of Mourning

- Accept the reality of the loss.

- Work through the pain of grief.

- Adjust to an environment in which the deceased is missing.

- Find a way to form an enduring connection with the deceased while embarking on a new life.

Accepting the reality of the loss is vital. In order to heal, we must first understand that we’re hurting and that something is not the same. Sadly, growth and change is often spurred by discomfort. While there are a number of ways to begin to either accept the reality ourselves or to help others, among the most effective are funerals/memorial services and using words that aren’t cloaked in platitudes or euphemisms. The loved one in question didn’t get lost, nor did he or she expire like a carton of milk. He or she died. People die. It’s part of the human life cycle, and it’s important to embrace this fact.

Working through the pain enables us to not feel stuck and to begin to find some level of healing. It keeps us active, engaged, and moving ahead, helping to keep us from feeling stuck. Will we feel stuck sometimes? Of course! As long as we remain open and honest, though, we will make our way forward in our own time and in a way that makes sense to us.

Adjusting to an environment in which the deceased is missing does not mean forgetting the person existed. It merely means understanding that our worldview has been irrevocably changed, and though the person is no longer physically present, our memories will keep them with us.

Finding a way to create an enduring connection means honoring the person through our actions and carrying them with us in our hearts. Pictures, favorite books, or even volunteer activities that you do in their memory can help create this lasting, meaningful connection. As long as we hold the person close to us and honor that connection, they are not lost to us, even if they may not be physically present.

Worden’s tasks allow grievers to move ahead at their own pace. Yes, they are placed in some semblance of order, but they are tasks, and not merely things that happen to us or thoughts, feelings, or emotions we are carried through in a passive manner – which is how a reliance on the Kubler-Ross model can often make people feel. Worden’s tasks are active. Worden’s tasks empower grievers, giving a greater sense of control than models like Kubler-Ross’s.

Worden’s model isn’t perfect, of course. It appears quite linear and it may also seem as though there is no room for sliding backwards amid the tasks. After all, grief is messy, and a griever may often feel waylaid by what Dr. Therese Rando calls “sudden, temporary upsurges of grief”, or STUGs. No matter how long it has been since our loved one has died, we are going to have moments when we are a complete mess and miss the person even more than we thought we could – and we may feel like all of our progress to this point has been for naught.

It’s important to remember, though, that on any journey, no matter the model we subscribe to, we stumble – and that’s especially likely on a journey like the one through grief that is never-ending. Whether we’re grieving or supporting someone who is, it is important to remember that we will stumble and struggle. These are not failures…they’re simply realities that happen. We may have moments of sadness, even though we feel as though we’ve moved far beyond that point – or we may have moments of joy when we feel as though it’s not appropriate. Never judge nor apologize for what you or someone else is feeling. That’s our subjective reality in the moment, and everyone is entitled to those feelings.

*****

About the author: Chad Harris is a graduate student at Hood College in Maryland, where he is pursuing a master’s degree in thanatology, as well as coursework in gerontology. He also holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Central Arkansas, as well as a master’s degree in social work from Case Western Reserve University. He is currently researching the role of mass media in shaping people’s perceptions of death and the impact of media coverage on grief and mourning, with the hopes of helping promote more responsible coverage of tragic events.