Alkaline Hydrolysis: Water Cremation and the “Ick Factor”

By Traci Rylands

Today’s guest post is a little graphic in describing how cremation works.

I recently wrote about the history of cremation in America and how it’s becoming more popular every year. However, an alternative form of cremation is gaining attention that’s truly different. Resomation, bio-cremation and flameless cremation are a few of the buzzwords used, but the scientific name for the procedure is alkaline hydrolysis (AH).

So how do you cremate a body without a fire?

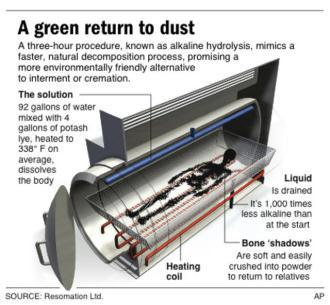

This graphic from Resomation, Ltd. explains the alkaline hydrolysis process. The company was founded in 2007 in Glasgow, Scotland by Sandy Sullivan. Ironically, AH is still not legal in the U.K. at this time.

Alkaline hydrolysis is a water-based chemical resolving process using strong alkali in water at temperatures of up to 350F (180C), which quickly reduces the body to bone fragments. Experts say it’s basically a very accelerated version of natural decomposition that occurs to the body over many years after it is buried in the soil.

AH was originally developed in Europe in the 1990s as a method of disposing of cows infected with mad cow disease. In England, AH for humans is not fully legalized yet. It’s usually referred to as resomation there because the commercial process was first introduced and trademarked by Resomation, Ltd. They received the Jupiter Big Idea Award (from actor Colin Firth, no less) at the 2010 Observer Ethical Awards.

Yes, that’s Colin Firth (aka Mr. Darcy) on the end. He presented the Jupiter Big Idea Award to Resomation, Ltd. at the 2010 The Observer Ethical Awards. The firm’s founder, Sandy Sullivan, is standing to his left. Photo courtesy of The Observer.

The University of Florida and the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota already use AH to dispose of cadavers. It’s not surprising that both states were among the first to legalize its use. The other states are Colorado, Oregon, Illinois, Kansas, Maine and Maryland.

But why would someone want to do what amounts to liquifying the body with lye instead of traditional cremation? Some people worry about the carbon footprint left behind by traditional cremation. AH is supposed to remove that problem.

In the traditional process that uses fire, cremating one corpse requires two to three hours and more than 1,800 degrees of heat. That’s enough energy to release 573 lbs. of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, according to environmental analysts. In many cases, dental compounds such as fillings also go up in smoke, sending mercury vapors into the air unless the crematorium has a chimney filter.

During AH, a body is placed in a steel chamber along with a mixture of water and potassium hydroxide. Air pressure inside the vessel is increased to about 145 pounds per square inch, and the temperature is raised to about 355F. After two to three hours, the corpse is reduced to bones that are then crushed into a fine, white powder. That dust can be scattered by families or placed in an urn. Dental fillings are separated out for safe disposal.

Anthony A. Lombardi, division manager for Matthews Cremation, demonstrates a bio-cremation (AH) machine. Photo courtesy of Ricardo Ramirez Buxeda/The Orlando Sentinel.

AH is purported to use about one-seventh of the energy required for traditional cremation. Some studies indicate that AH could save 30-million board feet of hardwood each year from cremation coffins. That’s very attractive to some people. However, one question remains. What happens to what’s leftover from the process (besides the ashes)?

That’s when the “Ick Factor” comes in.

Leftover liquids – including acids and soaps from body fat – plus the added water and chemicals, are disposed of through a waste water treatment process, according to John Ross, executive director of the Cremation Association of North America.

In other words, it goes down the drain like everything else.

“It’s very similar to the treatment of excess water from any (industrial) facility. In fact, it probably has less of a chemical signature than would you find (in liquids) coming out of most (industrial) plants,” Ross said.

Ryan Cattoni, funeral director at AquaGreen Dispositions LLC, offers the first “flameless cremation” in Illinois. Photo courtesy of Brian Jackson/The Sun-Times.

Still, the visual picture that creates is not very attractive. In fact, a 2008 article about AH said the thick coffee-colored liquid left behind resembles motor oil and has a strong ammonia smell. Not exactly something you want to put on a colorful marketing brochure.

AH became legal in Colorado in 2011. Steffani Blackstone, executive director of the Colorado Funeral Directors Association, spoke frankly about the “Ick Factor” when legislation to approve AH was being crafted.

“People seem to have objections when they actually think about that too long. They ask: ‘Well what happens? Does (the body) turn to sludge?’ And the thought of grandma being sludge is kind of disgusting to them.”

While currently legal in only eight states, the movement to make it so in others is real. In New York, the legislation became known as “Hannibal Lechter’s Bill.” New Hampshire legalized AH in 2006 but banned it a year later. In Ohio, the Catholic Church is a vocal opponent to AH and it has yet to be fully approved there.

Jeff Edwards, an Ohio funeral director who performed several AH procedures before being told to stop, filed a lawsuit in March 2011 against the Ohio Department of Health and the Ohio Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors after ODH quit issuing permits for AH body disposals. A judge ruled that ODH and the board had the authority to determine what is an acceptable form of disposition of a human body, as set forth in the Ohio Revised Code.

The cost of an AH machine can range from $200,000 to $400,000, depending on its size and capacity. That hefty price tag did not stop Anderson-McQueen Funeral Home in St. Petersburg, Fla., from becoming the first in the state to purchase one to provide AH to their clients. They refer to AH as “flameless cremation”.

Funeral home president and owner John McQueen said in a 2011 article that he planned to charge clients the same prices for AH cremations as the traditional ones, which can cost from $1,000 to $2,000.

Anderson McQueen became the first funeral home in Florida to offer alkaline hydrolysis to its clients. They call it “flameless cremation”.

So what do I think? In the end, traditional cremation sends its byproducts up into the air. AH sends them into the water for treatment. Which is better for the environment? I don’t know. I’m not fond of the idea of being burned up or liquified, especially the latter. The “Ick Factor” does give me pause.

A pine box in the cemetery still sounds better to me.

*****

Todays’ guest post is written by Traci Rylands of Atlanta, Ga. Traci writes, “I’m a photo volunteer for Findagrave.com, a database of cemeteries around the world. I enjoy learning about the stories of those individuals whose graves I find while educating others about death and dying.”

Please visit Traci’s blog, “Adventures in Cemetery Hopping.”

You can also like her blog on Facebook. And follow her on Twitter.