Should We Medicate Grief?

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is about ready to publish their Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5); and it’s created no small stir among the psychiatrist community.

One of the main issues that psychiatrists are having with the DSM-5 is that it is lumping normal grief into Major Depressive Disorder. Here’s a quote from Dr. Allen Frances, professor emeritus of Duke’s School of Medicine:

(In the new DSM-5) Normal grief will become Major Depressive Disorder, thus medicalizing and trivializing our expectable and necessary emotional reactions to the loss of a loved one and substituting pills and superficial medical rituals for the deep consolations of family, friends, religion, and the resiliency that comes with time and the acceptance of the limitations of life.

*****

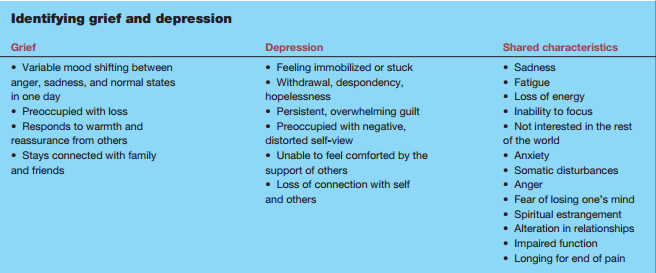

There are many shared characteristics between grief and depression, but there’s also some distinct differences. Dr. Ginette G. Ferszt states this:

Although everyone grieves differently, grief and depression share several common characteristics. Both may include intense sadness, fatigue, sleep and appetite disturbances, low energy, loss of pleasure, and difficulty concentrating. The key difference is that a grieving person usually stays connected to others, periodically experiences pleasure, and continues functioning as he rebuilds his life. With depression, a connection with others and the ability to experience even brief periods of pleasure are generally missing. Sometimes people describe feeling as if they have fallen into a black hole and fear they may never climb out. Overwhelming emotions interfere with the ability to cope with everyday stressors.

Here is a chart that shows the similarities and differences between depression and grief.

*****

Should we medicate grief?

Mostly “no”, but in some cases “yes”. Here is when grief may need some type of medication:

- If grief-related anxiety is so severe that it interferes with daily life, anti-anxiety medication may be helpful.

- If the person is experiencing sleep problems, short-term use of prescription sleep aids may be helpful.

- If symptoms last longer than two months after the loss and the diagnostic criteria are met, the person may be suffering from Major Depressive Disorder. In this case, antidepressants would be an appropriate therapy.

Here is are some criteria to determine if grief has transitioned to Major Depressive Disorder.

- Feelings of guilt not related to the loved one’s death

- Thoughts of death other than feelings he or she would be better off dead or should have died with the deceased person

- Morbid preoccupation with worthlessness

- Sluggishness or hesitant and confused speech

- Prolonged and marked difficulty in carrying out the activities of day-to-day living

- Hallucinations other than thinking he or she hears the voice of or sees the deceased person. (From Nancy Schimelpfening’s “Grief and Depression”).

Ultimately, grief is the response to loss. And no amount of medication is going to bring that loss back. We must learn to live with the loss of someone integral to our very being. If medication hurts that learning process, then it’s destructive. If it can help us learn to live in the “new normal”, then it becomes an aid to understanding life after loss.

I think the following quote sums up the core of why medicating grief is usually not healthy: