Finding a Context for Grief: A Guest Post by Jason Hague

“Jason, listen. I think I found a lump.” Karen’s eyes were full of gentle severity. “But hey, we’re okay. We’re gonna get through this. It isn’t our first rodeo.”

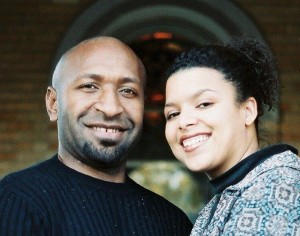

Karen was too young for cancer—just thirty four—and full of life. She and her husband George had been my friends for nine years, and part of my family for the last five. They were missionaries, planning to launch out to the South Pacific to eventually start an AIDS orphanage. And after countless encouragements, they believed with all their hearts that she would be healed. After all, she had beat cancer before when she was seventeen, and again (we thought) at thirty-two. That’s why she was so confident.

So they entered the rodeo a third time, pursuing all kinds of treatments; the ones that come from sober doctors in white hospitals, and the other ones from enthusiastic Americans with juicers in Mexico. They got prayer. Lots of prayer, from reserved, gray bearded conservatives, and from young mustached mystics who claimed they saw miracles happen every day.

They went on like that for months, traveling the country, raising funds for their move to the islands, all the while believing against the obvious. She was getting weaker. And weaker.

I got the call while watching a college football bowl game. Karen had collapsed and had a seizure. She was in intensive care. Even brain now, it seemed, was being squeezed by cancerous masses. The doctors were saying it was time.

Before I got in the car for our five hour trek to the hospital, I had an awkward stare-down with my pinstriped suit. As a rule, I don’t wear suits except for mandatory formal occasions. I knew the odds this time. But if I took it… what would that say about my level of faith?

I remember stomping out of my bedroom, tears shaking me from the inside. “Fine, God. I’m leaving the damn suit.” I said aloud. It was as much belief as I could muster in that moment.

Four days of blur followed, and finally, our remaining hope disappeared with our emotional strength. The nurses—Lord bless them—let me sneak my daughters into the ICU to say goodbye to their adopted auntie. She was too weak to say anything, but she hugged them limply. And to each of us, her circle of friends who had become kin, she spelled out farewells on a whiteboard full of letters.

I was in the room when her breath ran out. George was still embracing her, still serenading her body. “You are so beautiful to me.”

I would need my suit after all.

They wanted me to do her funeral, but I just couldn’t. All I could muster was a couple of weak stories about being together, watching Jack Bauer and dreaming of all the exotic ministry we were going to get to do one day. It all seemed so empty. So hollow.

I told God how much it hurt. I didn’t blame Him for her death, but I thought it was a pretty low thing of Him to do, giving words of hope when no hope, in fact, remained. God didn’t answer much. He mostly just listened. I don’t think He ever got offended by my doubts, or my cursing, or my anger. Wasn’t it Jesus, after all, who said to weep with those who weep?I wonder if you can’t talk someone out of pain, even if you’re God.

But eventually, I knew I had to make a decision. I could hold onto my complaint against Him, but only on one condition: I had to first acknowledge His generosity. He had given her seventeen years before she met cancer, then seventeen more after that. He gave her life. Karen was His present to all of us. And in this age, there are no presents that last forever.

So I made a decision to look God in the eye again and thank Him for my friend. This wasn’t so much a matter of religious sentiment as it was intellectual integrity. When gratitude is absent, mourning eventually loses all context and reason. It’s the same lesson I try to give my kids: to say “thank you for my ice cream” instead of pining hard for a second bowl. Even a gift cut short is, first, a gift.

Looking back, I see my own tears had testified of my great privilege: Karen was so lovely and gracious and warm, and I had been her friend. Her brother. Little did I know, my grief was itself building a case for the love and graciousness and warmth of her Maker.

And it made me look forward to the next age, when the Good and Perfect Gifts of our Father will indeed go on and never expire.

*****

Jason Hague is a pastor, writer, and former Youth With A Mission teacher who lives in Oregon with his wife and five Children. He tells honest stories of faith, culture, and autism at JasonHague.com.