Dying Well

Remember Edie Norton

It’s rare that I share a funeral related story and include the deceased’s actual name. Except for my personal family, I almost always change the names of those involved for the sake of their privacy. I’m making an exception for Edith “Edie” Norton and Brian Wilson.

—

The world goes around because there are people who give more than they take. Some of those people become well known, but most go about their lives unrecognized. Edie never received recognition for her life’s work, likely because her life’s work was focused on just one person.

—

Brian Wilson had nonverbal autism and needed constant personal care. At one year of age, Brian’s parents knew they needed help raising him, so they hired Edie, a young woman with a bachelors degree in psychology.

—

Because both of Brian’s parents worked demanding jobs, Edie was at Brian’s side 24/7. Her “job” wasn’t a 9 to 5, it was a life commitment, one that she honored until Brian died last year at the age of 33.

—

A little over a year after Brian died, Edie passed away on November 2nd at the age of 69. I met with her siblings to make the funeral arrangements (Edie never married or had biological children of her own). In the obituary, Edie’s family wanted it mentioned that she cared for Edie as a son. But Brian was more than a son, he was the center of her day, the center of her daily actions, her daily thoughts and her life.

—

I want you to know about Brian and Edie. Edie life and death won’t be covered by the news, but she cared for someone who couldn’t care for himself. And although their lives were somewhat isolated, and although their names won’t be written in the annuals of human history, they did find the magic that makes the world go round. And I’d like for you to remember their names today.

“Dad, it’s okay to die.”

Author: Beverly & Pack

Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/walkadog/

Year: 2009

Source URL: https://www.flickr.com

License: Creative Commons Attribution License

The death call came early in the morning. I put on my dress clothes, drove to the funeral home, and scooted out of the funeral home parking lot at around 4:30 AM to the Veteran’s Administration Hospice Center.

A half-hour later I rolled into the VA parking lot, pulled into the ambulance entrance, and hit the buzzer by the door to alert the nursing staff I had arrived.

He was a small guy, no more than 120lbs. He was 81 years old. There was a rolled hand towel underneath his chin to keep his mouth closed. He was in a fresh gown that the nurses had put on him after they cleaned him up for the final time. A patriotic honor blanket — used by the VA hospice for all deaths — was draped over his abdomen and legs.

I noticed immediately that his hands and feet were wrapped tightly in bandages, which usually means that the deceased has fragile skin that easily rips, or he or she was a diabetic with circulation problems that plague the extremities, especially near the end of life.

This man was going to be cremated. So, when I got back to the funeral home, I felt his chest area for a pacemaker and found nothing (if he had a pacemaker, I would have had to remove BECAUSE THEY EXPLODE WHEN CREMATED!). I then unwrapped his hands to check for rings. What I found surprised me: his fingers were totally necrotic. I had seen diabetic tissue necrosis, but it’s usually amputated before it gets this bad. His pinky finger was no longer attached to his hand. And it didn’t look like it had been cut off. There was no clean incision. It looked like it had fallen off or broken off.

I took the bandages off the right hand, mainly looking to make sure there weren’t any rings on that hand, but I was also curious to see if that hand was necrotic as well. It was worse. Black skin. Shriveled. And only two fingers remained on a hand that bore no resemblance to human flesh. You’ve seen the pictures of the bog bodies? That. It looked like that.

Part of me wanted to unwrap his feet, just to see what damage had been done to his toes. But there was no pragmatic reason to see what was hidden underneath those dressings, so I let them be. Had he lived any longer, I’m sure his hands and feet would have been removed. He would have been wheelchair bound and mostly dependent upon the help of others to do his daily tasks: eating, bathing, cleaning, brushing his teeth, combing his hair.

I met with his two daughters at 11 AM the same morning.

As is my custom, I like to ask questions about the deceased’s final days. It allows me to get to know him a little more, and understand where the family is at both practically and psychologically. It’s the little details I’m interested in, like:

Have you guys been able to sleep the last couple days?

Was your dad able to communicate with you guys until the end?

Did this all happen quickly, or was it a slow, downhill process?

As we talked, they painted a picture of a man who was a fighter.

This poor guy had it all.

He had developed type 2 diabetes in his late sixties; diabetic kidney disease in his early seventies; he had been on dialysis for years, and soon the heart problems came along.

“I’m going to beat this”, he would tell his daughters time and time again.

As things progressively got worse, he dug in deeper because he vowed “not to quit.”

Just a year early he was diagnosed with a heart problem (I forget what exactly the problem was) that could only be fixed with surgery. Even though the doctors gave him a 20% chance of making it through the surgery, he decided to do it. And he made it, but it left him weaker than he was before the surgery. Soon the necrosis came. The doctors recommended that his hands and feet be amputated.

“That’s when we had a heart to heart talk with him,” the girls said.

“‘I don’t want to give up’ was his battle cry”, they told me. “He didn’t want to fail. He was a vet. He came from a hard family life. He worked hard his whole life. He put us both through college. He had this mentality that he was going to pull through no matter what life threw at him.”

The girls recounted what they told him:

“Dad, you’re a strong man. You never gave up. You’ve loved us until the end. And Dad, it’s okay to die. Don’t look at this as a battle lost, look at it as an honorable discharge.”

“I don’t want to fail you girls,” he told us. Their eyes started to well up with tears as they recounted the conversation.

“We told him that he’s never failed us. We told him that knowing when enough is enough isn’t the same as giving up.”

“We wanted him to know that coming to the end of the journey isn’t a failure, but a victory.”

They continued by telling me that he found peace, stopped dialysis, and welcomed death towards the end. Because death isn’t a failure.

Because it’s okay to die.

It’s okay to die.

*****

If you like my writing, consider buying my 2017 Nautilus Book Award Gold Winner, Confession of a Funeral Director (click the image to go to the Amazon page):

Thoughts on John McCain’s Cancer Diagnosis and Why Death Positivity Needs to Reframe Cancer Talk

Author: Gage Skidmore

Author URL: https://www.flickr.com/people/gageskidmore/

Title: John McCain & Mitt Romney

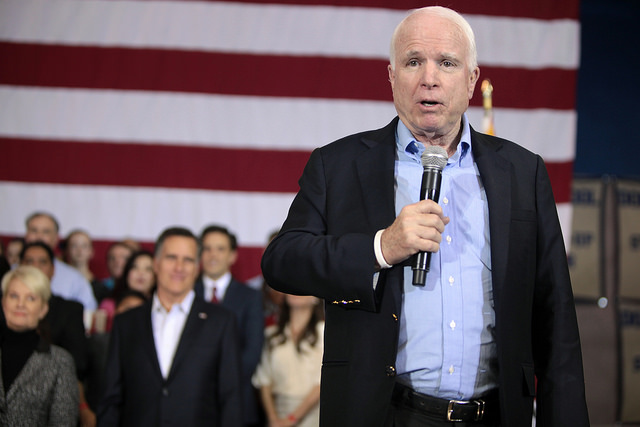

This week we were informed that Senator John McCain was diagnosed with malignant glioblastoma. The median survival for patients with malignant glioblastoma is 14 months, while roughly 10% of those diagnosed live up to five years.

John McCain is the definition of brave. He was a prisoner of war in Northern Vietnam for five and half years. For over a year of McCain’s imprisonment, he was beaten continuously, sometimes twice a day, in an attempt to break him. As a result of his beatings, he’s is unable to raise both of his arms above his head. Despite the brutality that he suffered for being an American sailor, after his retirement from the Navy he continued to serve his country as a congressman and senator from 1982 until today.

Naturally, knowing John McCain’s history as a sailor and tenacious public servant, the language that people have used to encourage him after his cancer diagnoses have mainly been war language. President Obama tweeted this:

John McCain is an American hero & one of the bravest fighters I’ve ever known. Cancer doesn’t know what it’s up against. Give it hell, John.

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) July 20, 2017

It only makes sense that we’d use such language for a warrior such as John McCain, but, oddly enough, when it comes to cancer, most of us default to war language for the stay-at-home mom who has breast cancer, for the auto-mechanic with lung cancer, for the construction worker with skin cancer.

We say things such as this:

“John is fighting courageously against cancer.”

If John’s cancer goes into remission, we say something like this:

“John beat his cancer”

And if someone dies from cancer, we see obituaries state,

“Sadly, John lost his battle with cancer.”

There are a couple problems with this cancer language, problems that need to be informed by death positivity. When we start from the basis that we are mortal, war metaphors start to fail because mortality is our lot, it’s a part of who we are and fighting against this aspect of ourselves leads to this fragmentation, where we assume that death is something other than us, something that is foreign, something that needs to be battled, something that we need to fight against. We are both alive and mortal and instead of seeing our mortality as foreign, the better way and the better language is to see our mortality as part of our journey. We are journeying through cancer treatment, we are still living our life amidst our sickness, we aren’t letting cancer define us, nor are we letting “the battle” define us.

Writing for the Guardian, terminal cancer patient Kate Granger summed up this idea of embracing our mortality when she wrote this:

Some days cancer has the upper hand, other days I do. I live with it and I let its physical and emotional effects wash over me. But I don’t fight it. After all, cancer has arisen from within my own body, from my own cells. To fight it would be “waging a war” on myself …. As a cancer patient who will die in the relatively near future, I believe rather that instead of reaching for the traditional battle language, [life] is about living as well as possible, coping, acceptance, gentle positivity, setting short-term, achievable goals, and drawing on support from those closest to you.

Certainly, we love life. We want to see our children get older, we want to be around our friends, but sometimes with cancer, it’s okay to accept that we will die. It’s okay to stop the treatment, not because we’re “giving up the fight” but because we recognize that we’re mortal. You’re not “losing the battle” when you have terminal cancer and you decide to forego further treatment. In fact, sometimes the brave act is in accepting the future, accepting the terminal prognosis and deciding to live your life to the fullest sans the body breaking treatment of chemo and the rigors of doctors visit after doctors visit. If we use the journey language, we recognize that it’s not about who lives the longest, but who lives the best. It’s about the best journey, not the farthest journey. It’s about living life to the fullest, not living forever. The language of journey reframes our understanding and it takes away the shame and possible guilt one might feel if we use terms like “losing the battle” and “giving up.” You are not “giving up” if you decide that it’s best to stop your treatment, it could be said that you’re bravely living your journey.

Finally, if you die of cancer, you didn’t lose. This idea that you’re somehow a loser if you die from cancer is perhaps the biggest problem with war language. Kristen Garrison writes:

How can a woman with metastatic bone lesions read Lance Armstrong’s story of conquering the disease and feel anything but failure? His story may be true, but does not represent the average person, and such narratives, which get so much press attention and bookshelf space, undercut the comparably determined but unsuccessful efforts of people fighting cancer.

Let’s bring this back to John McCain. John won’t be a loser when he dies from this cancer. He was and will continue to be a lauded individual who served his country in multiple fields. He was one of the bravest soldiers during Vietnam. And dying from cancer that will kill him won’t change that. Neither will it change you or me if our fate is the same. Some of the best people have died from cancer, and some of the worst people have managed to find remission. My journey, your journey, and John McCain’s journey will not be said to be a lost battle at our very end. This is our lot. This is who we are. We are mortal. And our character and our journey will be defined by our choices, not random, abnormal cell growth.

If you want to learn more about a death positive narrative, I have a book recommendation for you:

The Good Death: 10 Things I Want and Don’t Want When I Die

© 2010 Lee Haywood, Flickr | CC-BY-SA | via Wylio

One. I don’t want to prolong my life at the expense of quality.

We all know that the word “euthanasia” means “a good death”. The antonym of “euthanasia” is “dysthanasia” which means — you guessed it — “a bad death.” On a more practical level, “dysthanasia” is “generally used when a person is seen to be kept alive artificially in a condition where, otherwise, they cannot survive.” The bad death is a modern, medical induced phenomena where every attempt is made to hold back the inevitable; and yet, as Luis Buneul states, it ends up being an “exquisite form of torture.”

Two. I want to die at home.

I want to die at my home, surrounded by my family.

Three. And if I die at home, I want hospice.

Atul Gawande writes in his New Yorker piece,

(Doctors) sacrifice the quality of your existence now—by performing surgery, providing chemotherapy, putting you in intensive care—for the chance of gaining time later. Hospice deploys nurses, doctors, and social workers to help people with a fatal illness have the fullest possible lives right now. That means focussing on objectives like freedom from pain and discomfort, or maintaining mental awareness for as long as possible, or getting out with family once in a while. Hospice and palliative-care specialists aren’t much concerned about whether that makes people’s lives longer or shorter.

Four I don’t want to die in a nursing home.

I don’t like nursing homes. Let me qualify that statement: I understand that nursing homes are at times necessary and I understand that nursing homes provide invaluable care for those who need it; farther, I know that the nurses and their staff provide continuously care often at their own emotional expense.

But, I don’t likely the crowded loneliness inherent in these buildings, I don’t like the way nursing homes suck away money and I don’t like how some nursing homes are used to shelve away the weakest people in society.

Five. If the chance presents itself, I’d like to die heroically.

Sacrificing my life while saving drowning orphans from a sinking boat.

Dying while defending the rights of unicorns.

Pulling a James and Lily Potter: Giving my life to save my son from Lord Voldemort.

Six. I want the option of Death with Dignity.

If I find myself in a situation where I have a terminal illness that will cause great family distress or personal pain, I want to have this option available to me.

Seven. I wouldn’t mind dying of cancer.

I know that’s a controversial statement, so let me qualify it: When cancer strikes the young and middle-aged, it’s always horrible per se. But, when it strikes the aged — in terms of comparison and contrast — it’s not always the absolute worst way to reach the inevitable. Sometimes it might be the best possible option. It allows you to say your goodbyes, “get your house in order” and provides a set period of “quality time” to spend with your family and friends. When I’m older, it’s a much better option than a sudden heart attack, dementia or a slow and methodical wasting away.

Eight. I want total honesty from my doctor.

I have some skepticism when it comes to the medical community, especially when it comes to end of life care. While I believe that most doctors are honest, there are ulterior motives when it comes to cancer treatment and the like. While most doctors explicitly lay out the options for their patients, some will lay out the options that pad their pockets and suck the system. I want to be socially responsible when I die. I don’t want to suck hundreds of thousands of dollars out of the system so I can live a couple more months. I want total honesty from my doctor.

Nine. I want the least pain possible.

I’m not going to be prideful. If I have the option to manage my pain, I’m going to take it.

Ten. I want my family to know my advanced directives.

If I don’t die saving them from Voldemort, I want my family to know my advanced directives so that — if a situation ever presents itself — they can feel confident that they know what I wanted. Although they might not agree with my advanced directives, or want them, at least they can know they honored my last wishes and so honored me in my death.

The Pain of Nursing Home Placement

© 2009 Ulrich Joho, Flickr | CC-BY-SA | via Wylio

Maybe it’s shame

Maybe it’s fear

Maybe it’s acknowledgement

That the end is near.

*****

Maybe it’s the halls

The impersonal room

That looks and feels

Like a living tomb.

*****

Maybe it’s the money

$500 a day

Eating retirement

And inheritance away.

*****

Maybe it’s the crowd

Of lonely souls

Who have death

As their only goal.

*****

Maybe it’s hurt

And maybe it’s the pain

That she doesn’t even

Remember your name.

*****

Maybe it’s the smell

Of those dying

That permeates the rooms

Of those left lying

*****

In beds so cold

While TVs fill

The hours and minutes

They’re trying to kill.

*****

Maybe it’s the inadequacy

You feel inside

That she cared for you

And now you can’t provide

*****

She birthed you

And nursed you

But you can’t reciprocate

And see this through.

*****

You tell yourself

“The staff is great”

And it’s true

There’s no debate.

*****

“This is for the best”

You have to say

Again it’s true

But it feels so grey.

*****

It’s hard and painful

And pricks the guilt syndrome

When you put a loved one

In a nursing home.